Visitors to the exhibition Funerary Portraits from Roman Egypt: Facing Forward will learn that the so-called “Composite portrait of a man” is no portrait of a man at all.

Painted delicately across a fractured wooden board, the man’s features—rough, dark hair, a wrinkled forehead, wide brown eyes, and a five o’clock shadow—seem to form a face. But the apparent assurance of its details and the presumed objectivity of the museum setting deceive the uninformed viewer.

The “man” is in fact a composite of an estimated six different portraits, each intimately connected to a person who lived and died in Roman Egypt. From the first to the third century CE, when Egypt was a province of the Roman Empire, Greek, Roman, and Egyptian cultures cross-pollinated with one another, and funerary portraits illustrate this exchange of ideas and artistic practices. Originally attached to a mummified body and buried underground, these panel paintings helped facilitate the afterlife and care for the person’s immortal soul.

As fate would have it, in the 1800s, the burials were unearthed and ransacked. Lauded for their Greco-Roman style, the paintings were torn away from mummified bodies, which were often discarded, and sold into the European art market. Stripped of their historical context, the paintings were then reconstructed in the image of idealized ancient Greek painting, reflecting burgeoning 19th-century ideas about portraiture and art.

Harvard received its composite portrait of a man in 1924 and acquired four other painted panel portraits and one sculptural mask between 1923 and 1965. Each of the works arrived in this reimagined form. Presented in the museums’ galleries, they appeared to visitors then (and to this day) as if direct ancestors of the European painting tradition.

“They are almost always displayed vertically against a wall, and that says a lot to a viewer,” said Jen Thum, an Egyptologist and assistant research curator in the museums, speaking of the hundreds of such funerary portraits that hang on museum walls worldwide. “It looks like it’s supposed to be on the wall. It looks like it’s supposed to be seen by people and consumed. It looks like they’re supposed to be European, and that’s not what they are at all.”

A New View of Funerary Portraits

Over the last few years, Thum and three other curators at the museums have collaborated on a thoughtful reexamination of these objects. A goal of presenting the true nature of the portraits dovetailed with a desire to honor the individuals once intimately connected with them. The culmination of the curators’ work is the powerful exhibition Funerary Portraits from Roman Egypt: Facing Forward, in which quietly daring scholarship builds on these objects’ millennia-old stories.

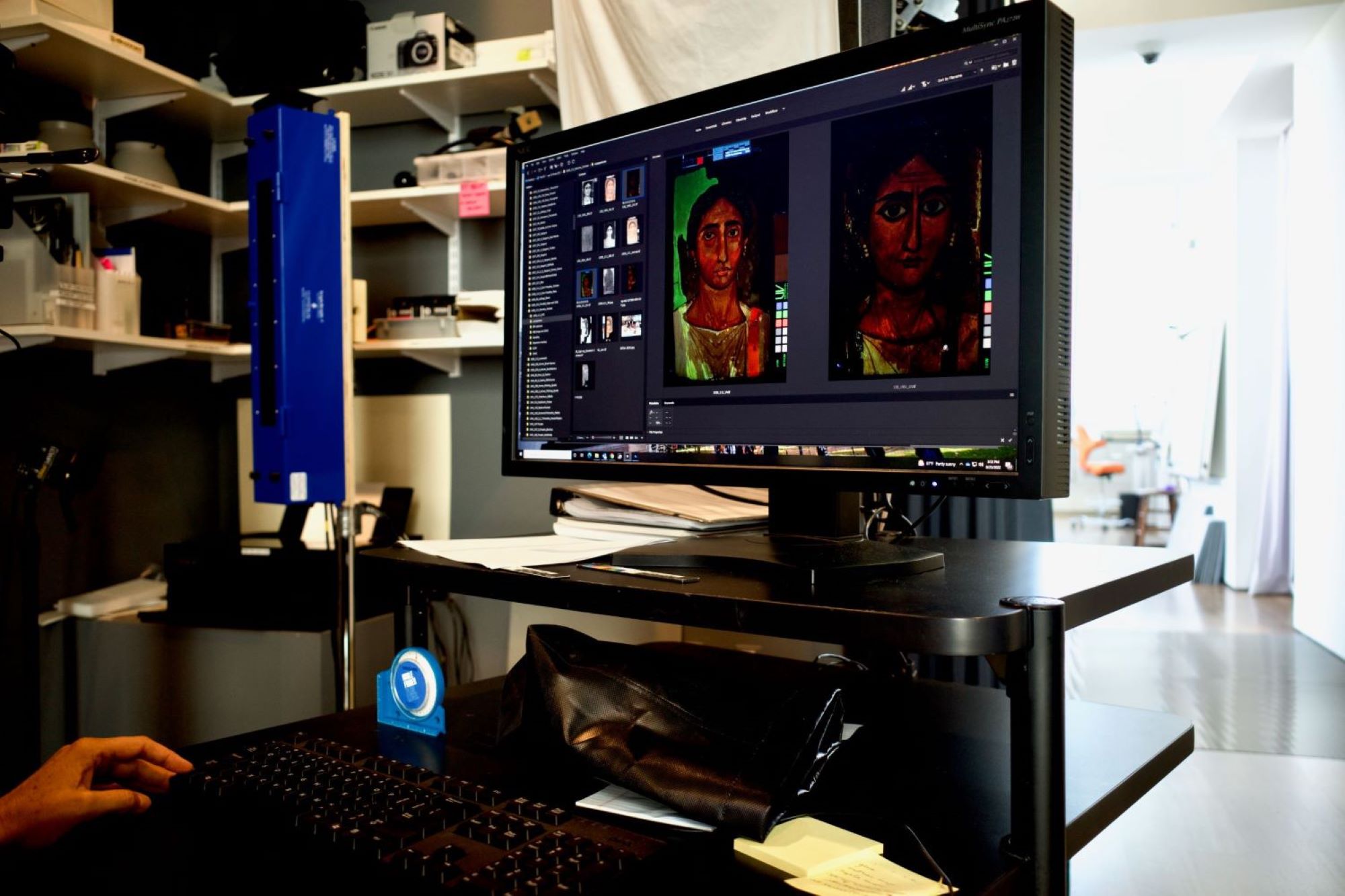

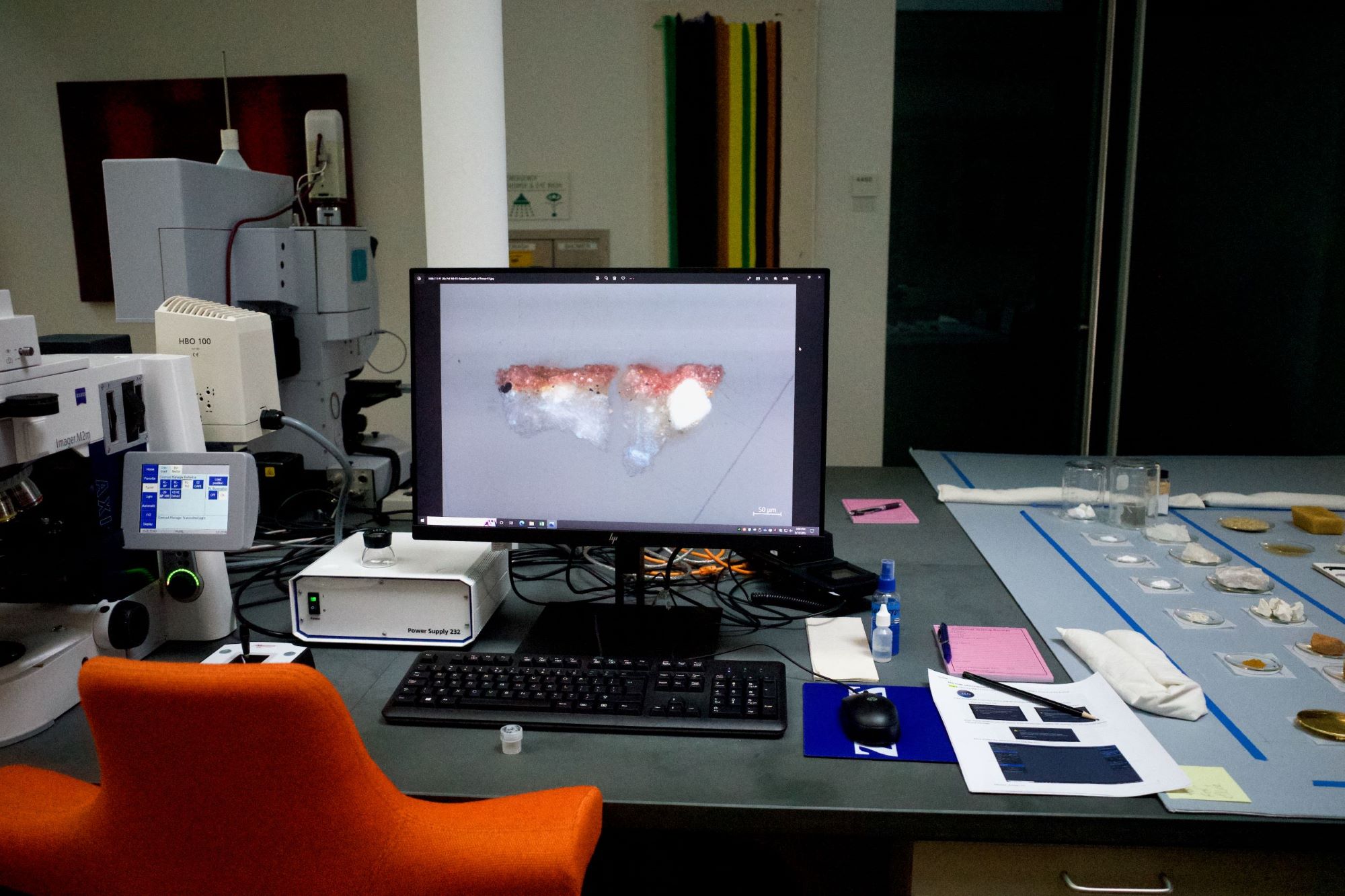

In the exhibition, open through December 30, 2022, ancient artifacts borrowed from other museums, such as burial shrouds, immerse viewers in the social and corporeal contexts of the funerary portraits. Diagrams, videos, and interactive re-creations bring cutting-edge material analysis and technical imaging into the galleries, foregrounding the ways artists created the objects as well as the fraught modern reception of the paintings.

Accompanying the display of the composite portrait of a man, for example, a video explains the processes and implications of such research techniques as X-radiography and ultraviolet-induced fluorescence imaging. These tools demonstrated that the object is a collage of at least six different Roman Egyptian funerary portraits. While some questions are answered, new questions are posed.

“Does it make sense to display the portrait as a modern assembly that tells the story of its life after burial?” the video asks viewers. “Or should we consider separating and displaying only those fragments that belong to the individual depicted in the central portrait? And if so, what should be done with the additional fragments?”

As visitors enter the exhibition, they are greeted by a commanding photomural of the present-day Fayum, a region of ancient Egypt where many of the portraits were found. A deep blue Nile River winds through golden-brown desert toward the sea, as verdant expanses and mountains unfurl alongside it.

Thum explains that the central motivation for using the contemporary image was to deflate the “weird, kind of mysterious rap” that popular media often assigns death in ancient Egypt—especially the notion that people of ancient Egypt were “obsessed with death.”

“We could have put an image there of a tomb or an excavation,” said Thum. “Instead of that, we chose this contemporary view in full color of a place where some of these people would have lived and also a place where people live today.”

The exhibition’s first room contains only one funerary portrait, a portrait of a man, which is positioned flat as it would have in a tomb. The subject’s short hair and beard suggest he died in the mid-third century CE, and the shape of the panel indicates that he lived in the ancient city of Philadelphia and was buried in the Fayum.

Susanne Ebbinghaus, the George M.A. Hanfmann Curator of Ancient Art and a co-curator of the exhibition, explains her hope that the portrait’s horizontal orientation will “startle visitors and really make them think about context. In other words, how do we bring in the body?”

So-called mummy tags—labels bearing the mummified person’s name—sit across from the portrait of a man and are among the ancient artifacts that curators hope draw out this context. The only surviving pieces of burial, these tags once identified the person in the embalming workshop and were critical to the subject’s identity in the afterlife.

“The idea of realistic, veristic portraiture was not important to the Egyptians,” Thum said, explaining that the portraits may be a stylized or idealized portrayal of a person. The most important individual identifier was one’s name.

“Your name is what lives on,” she said. “That’s why it’s so important that we have names in the gallery.”

Inscribed with ink or incised in Greek and Egyptian scripts, the wooden labels, which include names alongside other information, attest to the multicultural nature of the era and to the deeply personal character of the paintings. An exhibition label suggests: “Before you move on, consider speaking their names.”

Translations of four of the tags on view are:

Anoubion, son of Artemidoros, be of good cheer.

Plenis, the younger son of Marinas. He lived 35 years.

The Osiris Hor, son of Psenmonth, the stonecutter and priest of Imhotep.

Tasheret-kelendj, daughter of Kelendj, whose mother was Ta-akhemet. She died at age 13.