This digital resource is based on a printed booklet made available to visitors in the exhibition Objects of Addiction: Opium, Empire, and the Chinese Art Trade at the Harvard Art Museums. We have reproduced and expanded it here to make it accessible to those unable to attend the exhibition.

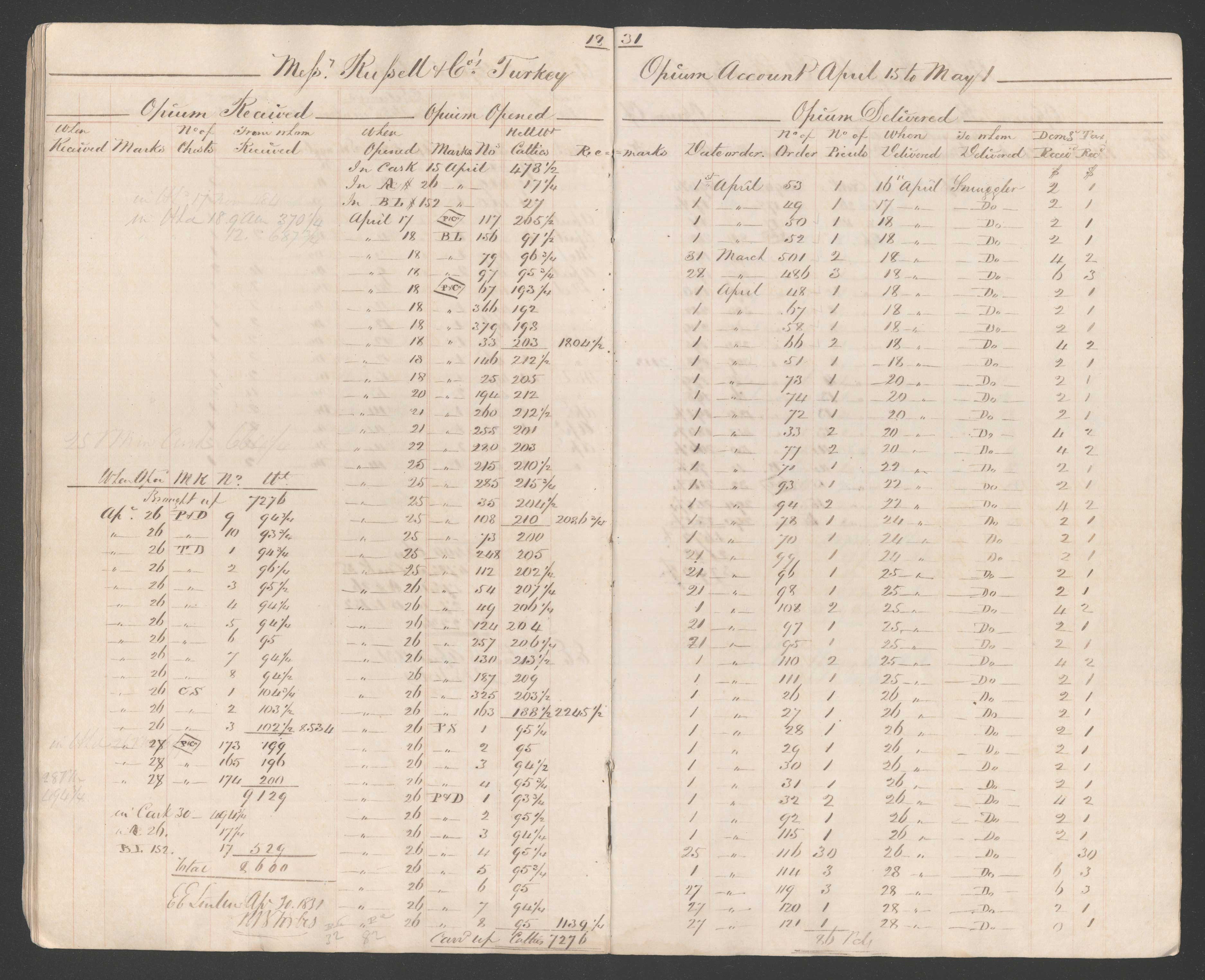

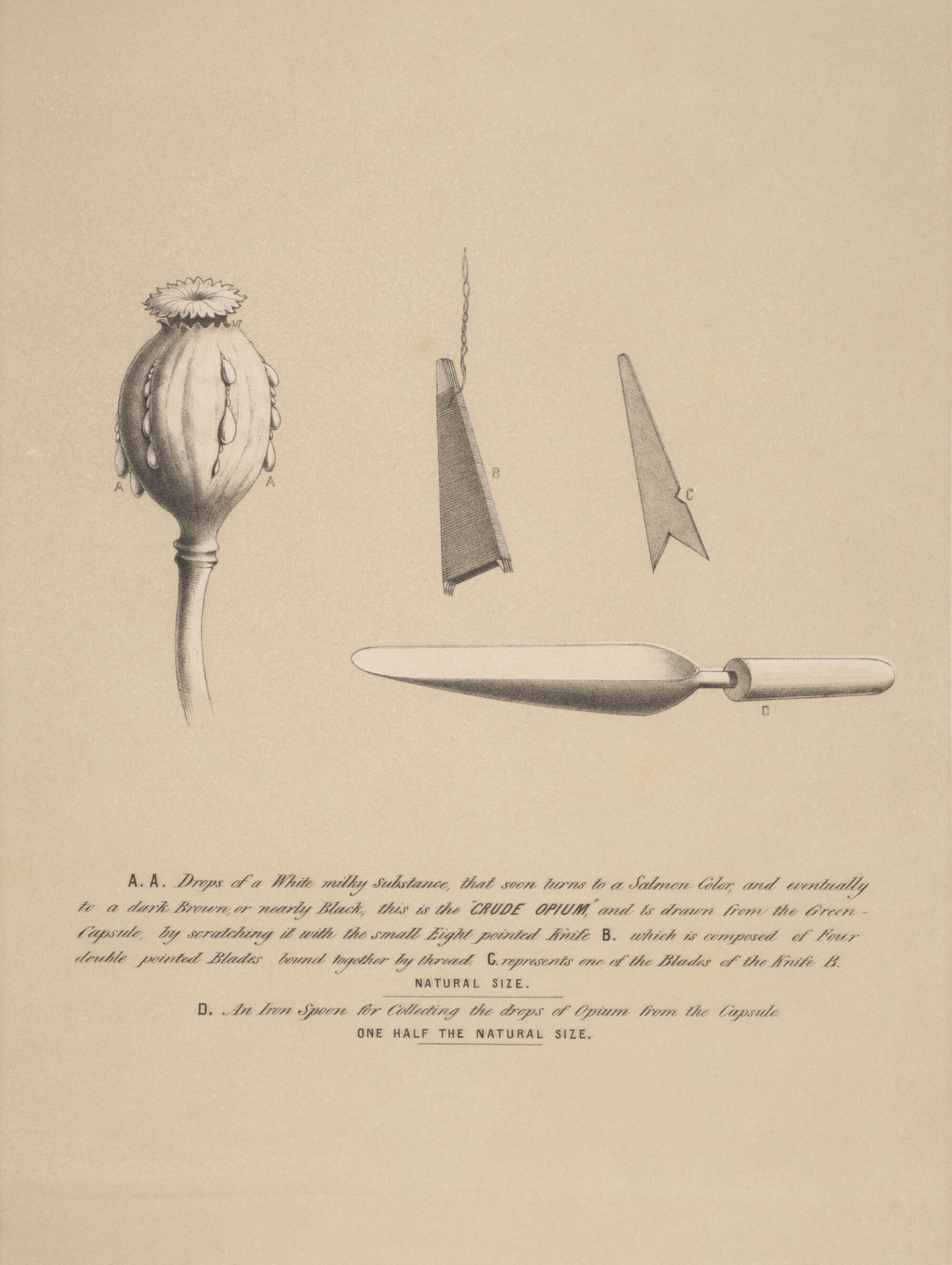

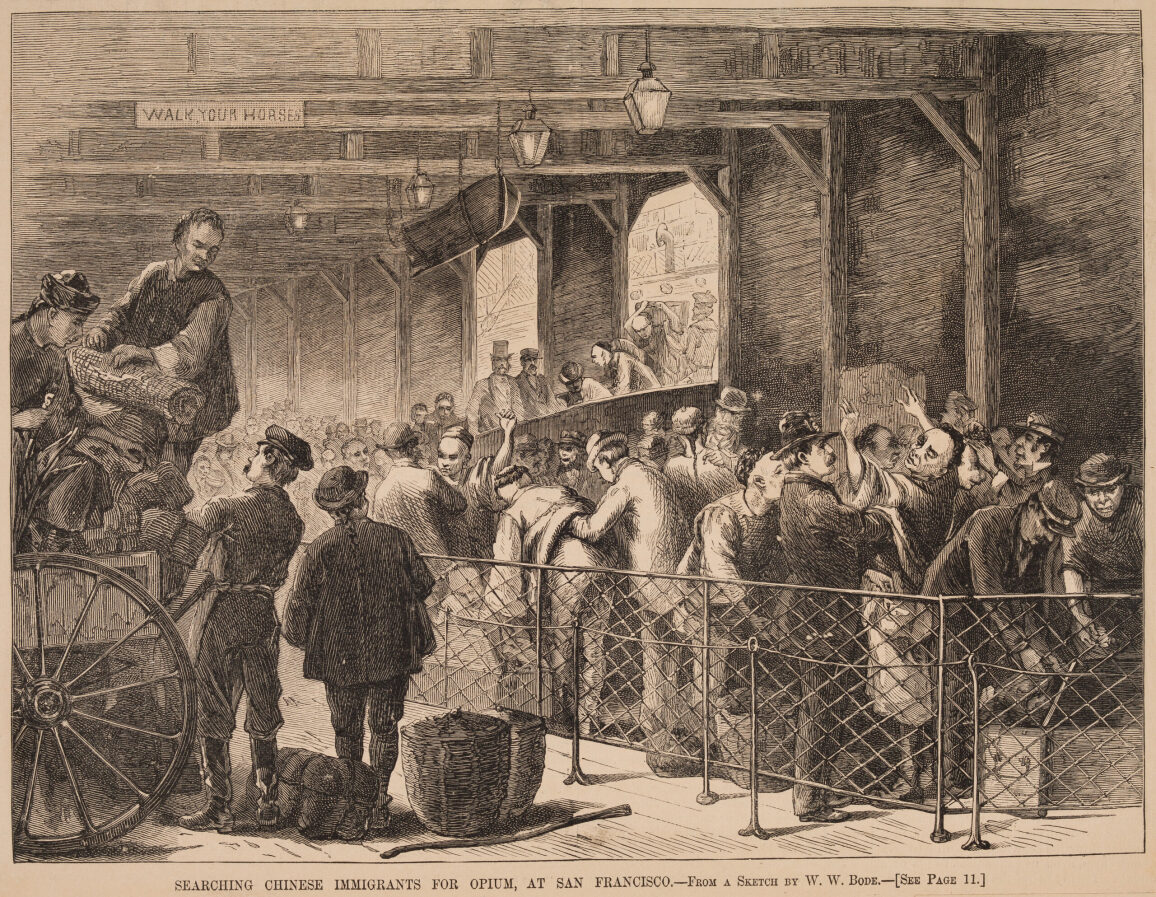

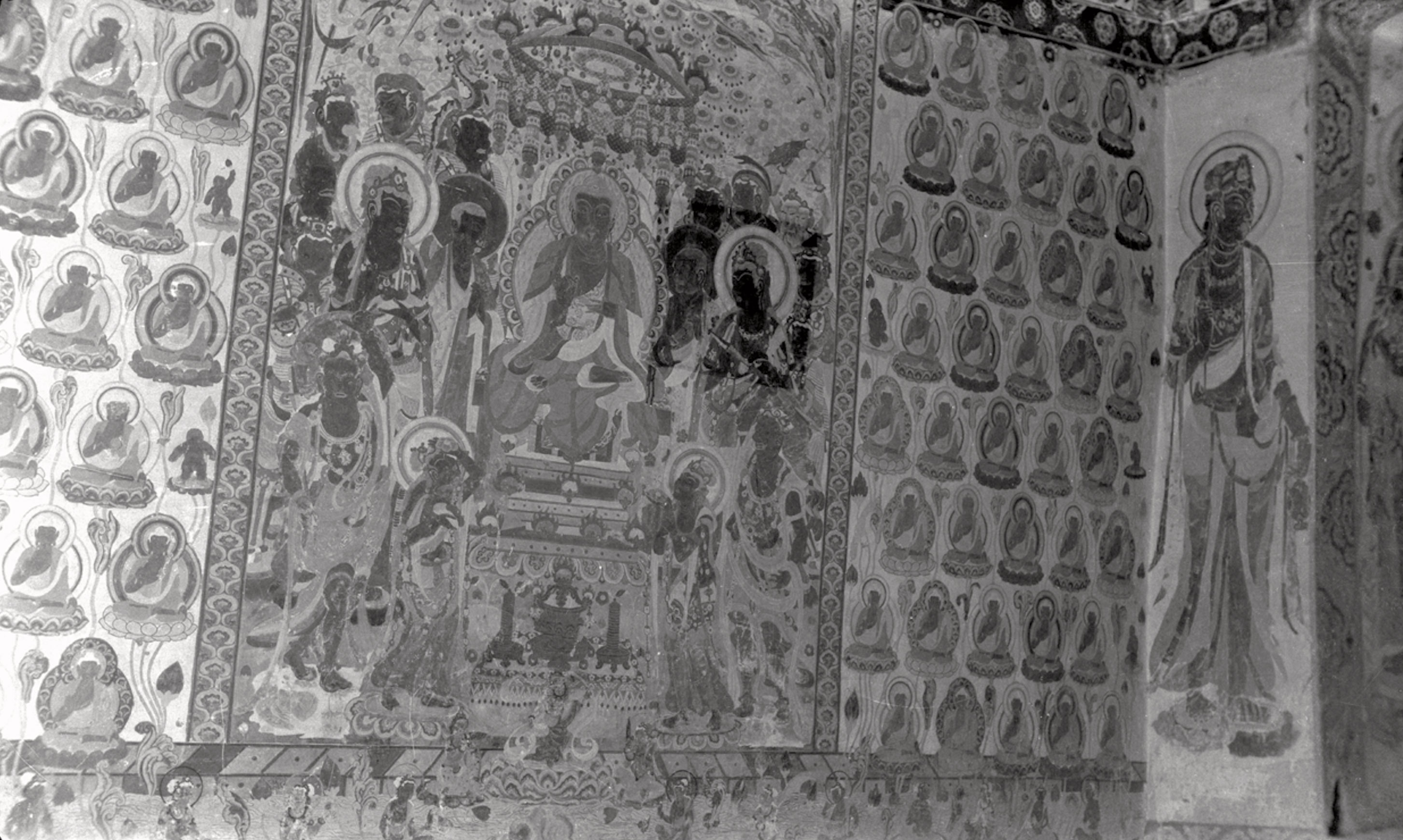

This exhibition explores the entwined histories of the opium trade and the Chinese art market between the late 18th and early 20th centuries. The first section examines the origins of the opium trade, the participation of Massachusetts merchants, and opium’s devastating impact on the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) and the Chinese people. Works presented include smoking paraphernalia, an opium account book, and photographs, along with mass media illustrations critiquing the use and sale of opium. The second section highlights the history of imperial art collecting in China and demonstrates the growing appetite for Chinese art in Europe and the United States after the Opium Wars (1839–42, 1856–60). Artworks from Massachusetts-based private and public collections show the shift in taste at this time from export ceramics and paintings to palace treasures and archaeological materials, including ancient bronzes, jades, and Buddhist sculptures. The essays in this booklet detail who has benefited from the opium trade, who has been harmed by the drug, and the legacy of opium in U.S. museums.

Who Has Benefited from the Opium Trade?

Opium was first banned in China in 1729 by the Yongzheng emperor (r. 1722– 1735) of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911). At that time, all trade with China was conducted through the Canton system, which restricted foreigners to the southeastern port of Guangzhou (known to westerners as Canton). During the trading season, merchants resided in “factories” that served as offices and storehouses, and transactions were overseen by a select group of Chinese merchants.