Founded in 1928 at the Fogg Museum, the Department for Technical Studies (now called the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies) was the first fine arts conservation treatment, research, and training facility in the United States. The recently installed materials collection in the Straus Center—made up of pigment samples, binding media, raw materials samples, historical scientific equipment, and a group of stone and mineral samples—showcases the museums’ history as a leader in the technical study of art. A microsampler created by the Fogg Museum’s first scientist, Rutherford John Gettens, is just one of the many historical instruments in the collection.

Conservation scientists analyze the structural and chemical nature of works of art and historical objects using a variety of methods. While noninvasive techniques are preferred, it is sometimes necessary to take a sample to determine, for instance, what materials lie below an object’s surface. In a 1932 article published in the Fogg Museum’s Technical Studies in the Field of the Fine Arts, Gettens wrote:

[T]he taking of micro samples from pictures must not be done indiscriminately. It must be done only as a last resort, when all other methods of settling a certain question fail or when no other method is applicable. The samples taken must be of such size that they are hardly visible to the naked eye, yet they must be intact as to structure and composition so that a single sample from one locality will furnish all the information that is desired.

Attaining this kind of sample is difficult, which is why Gettens set about building an instrument—called the microsampler, or “microsectioner”—to help this process. “It is hoped that this instrument will aid in solving many problems that arise in the routine examination and restoration of paintings,” wrote Gettens.

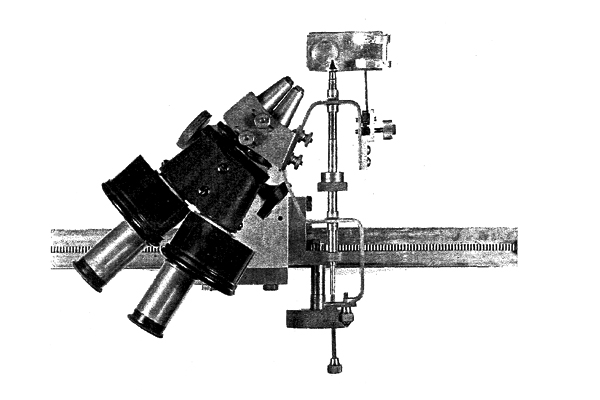

He designed his microsampler to be placed in front of a vertically mounted work of art, so that it could be positioned directly opposite the desired sampling location. Instead of incorporating a common needle to take a sample, which might crumble and mix the sample’s layers, Gettens mounted a hard steel hypodermic needle that was trimmed and tapered next to the nose of a binocular microscope. This way, the operator could have a clear and magnified view of the area he was sampling. The stand was adjustable, providing the user with flexibility and precision. The needle was fit with a wire that would eject the sample, or core section, which would then be mounted in a hard wax, where it could be analyzed under a microscope.

The historical instruments that will be on view in the Straus Center’s materials collection present some of the earliest examples of the laboratory’s use of cutting-edge technology. Although the microsampler is no longer actively used by the lab, the Straus Center continues to adapt and apply new technologies to the study of art, keeping the Harvard Art Museums at the forefront of conservation science.