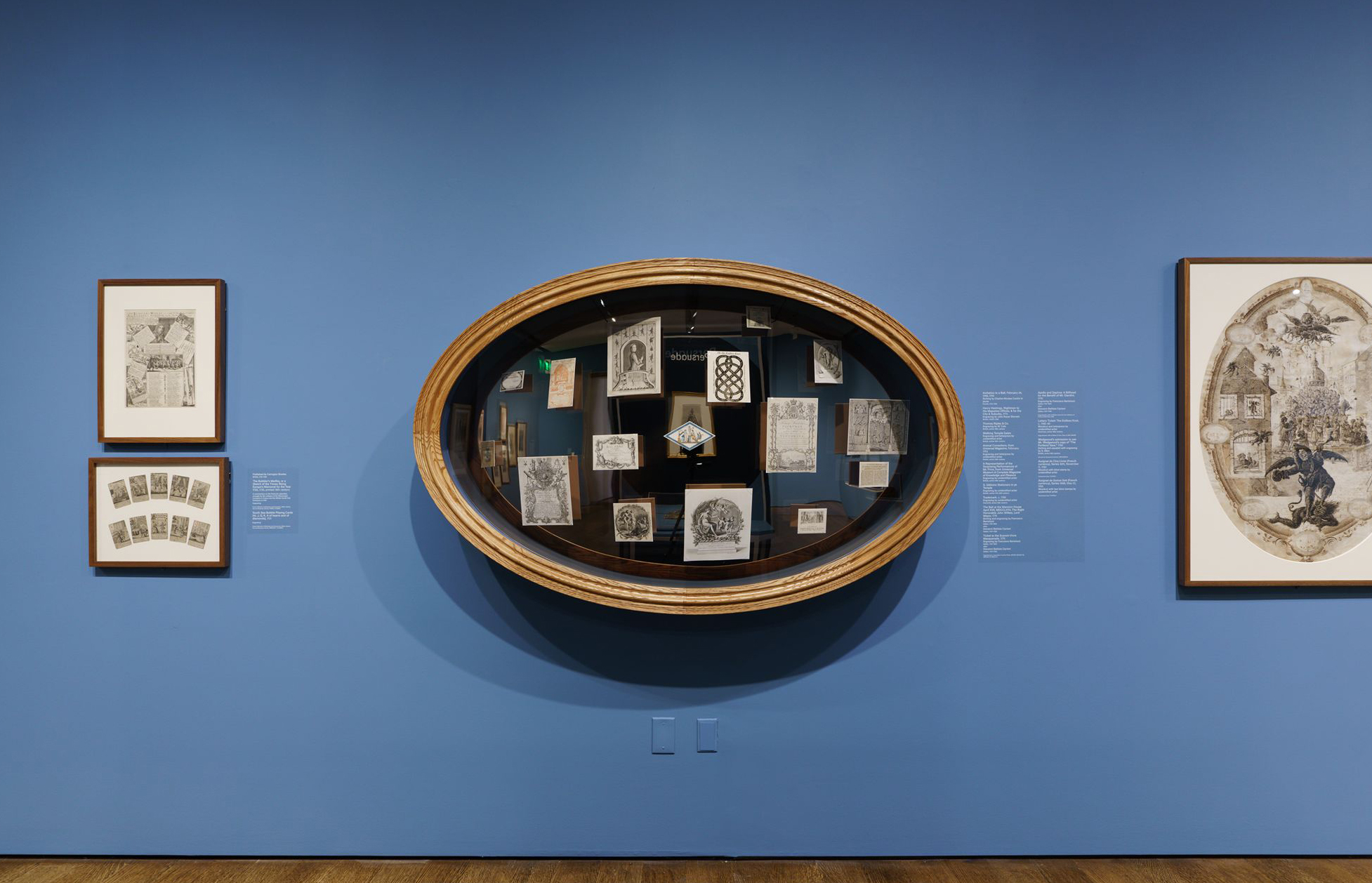

One of the great joys of being an exhibition designer is the opportunity to watch skilled professionals at work as they translate ideas into reality.

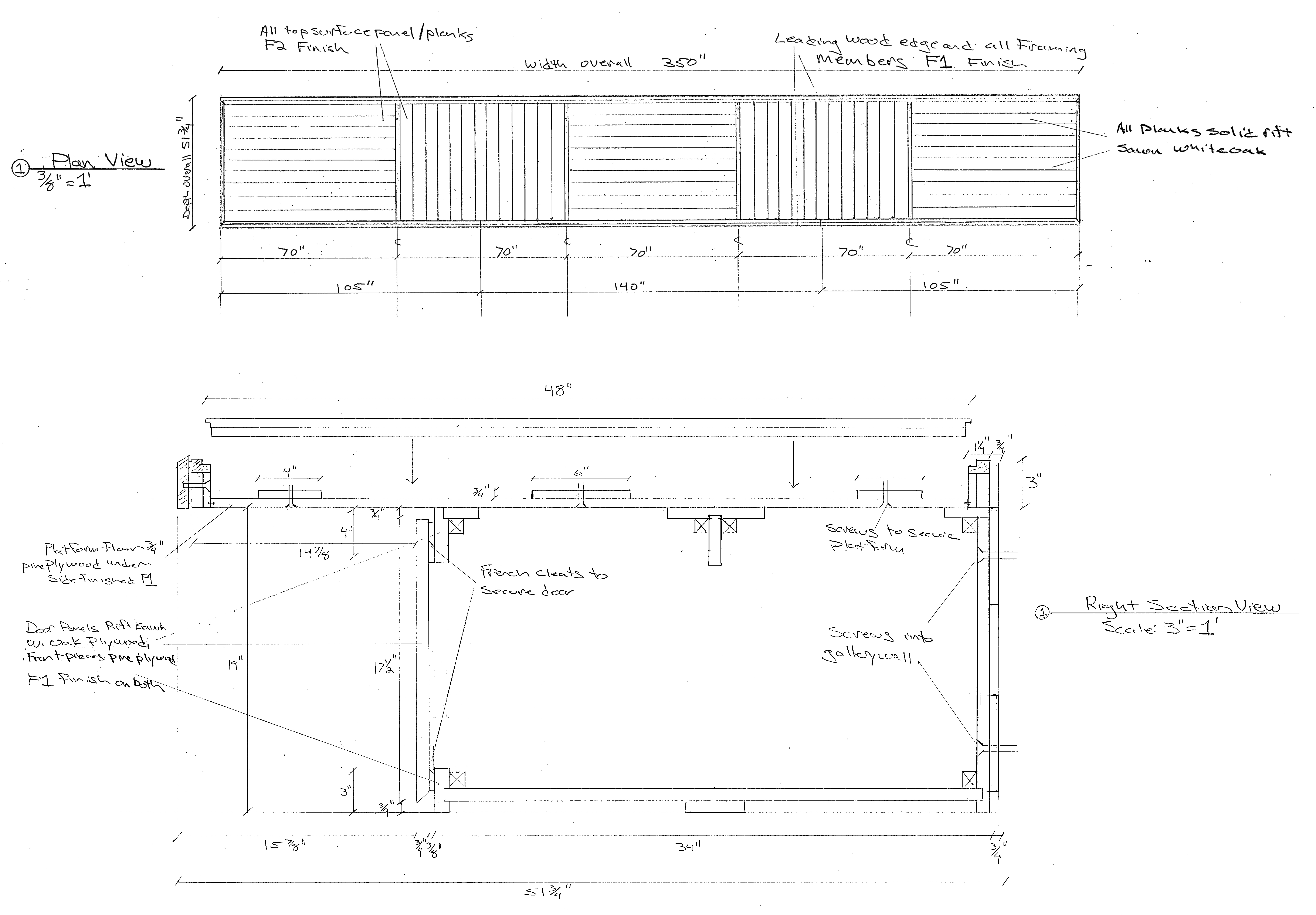

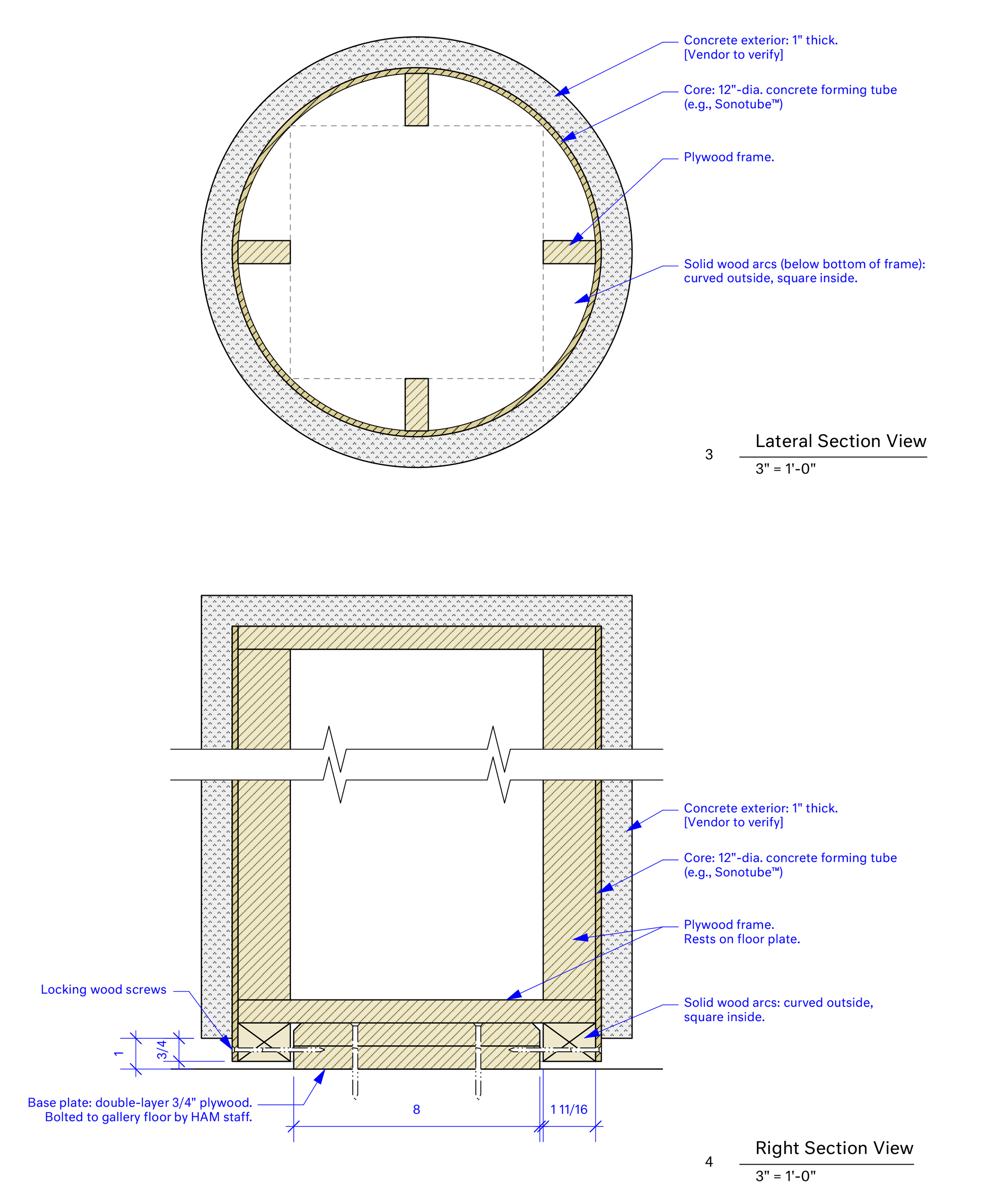

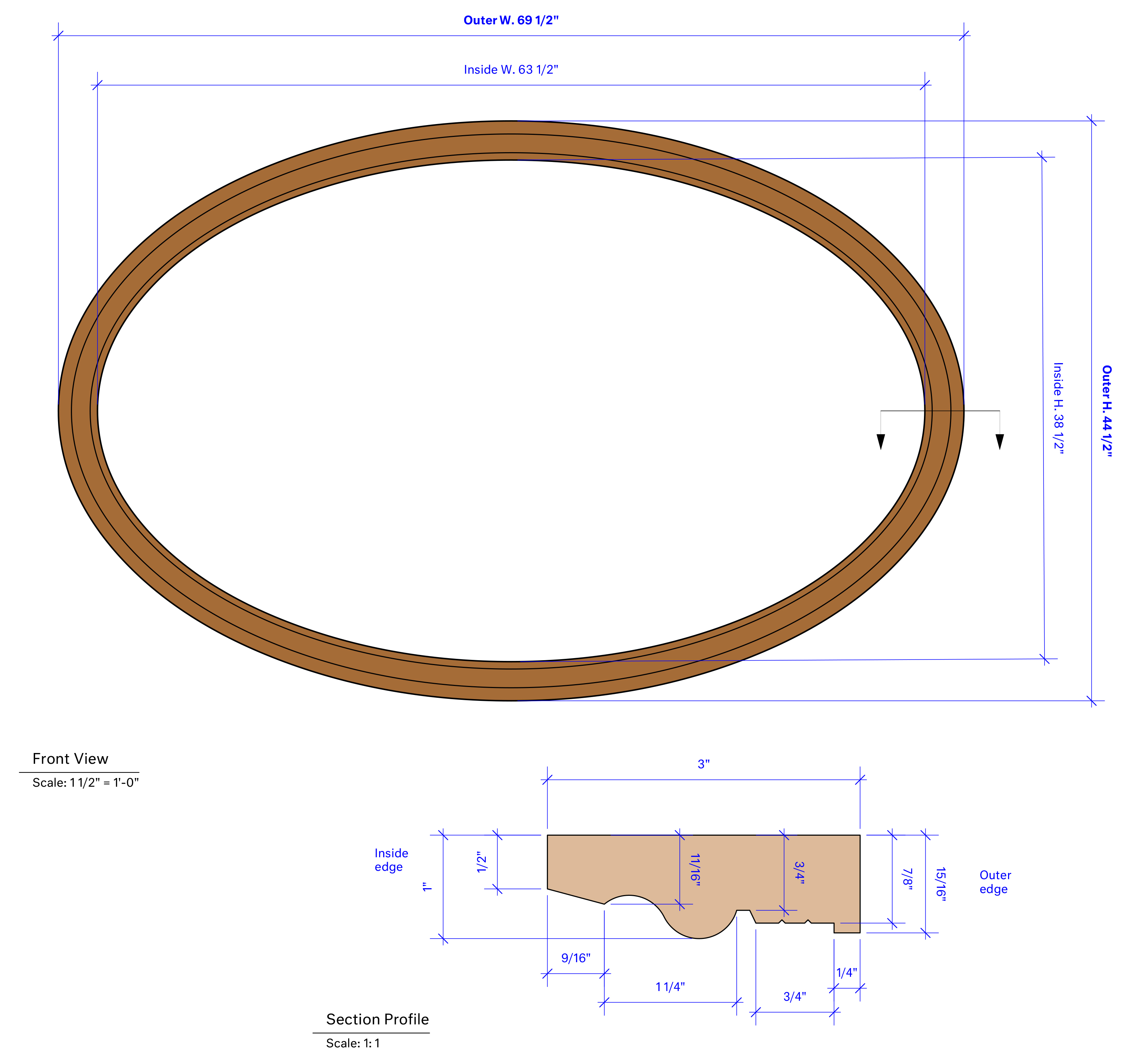

At the Harvard Art Museums, we have a robust schedule of exhibitions, monthly gallery changes, and special installations. Since art by nature is infinitely varied in size, format, style, and medium, and because we often have specific aesthetic goals for our presentations, we are frequently building custom furnishings (such as pedestals, mounts, and cases) to house and protect the objects on view. All this means that there’s usually plenty of work for the many talented individuals we rely on to build our stuff.