When it comes to the Art of Jazz: Form exhibition, on view in the Harvard Art Museums’ University Teaching Gallery, there’s much more than meets the eye. That’s because there are two other components to the show, both on view in the Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African & African American Art at Harvard’s Hutchins Center. The three-part exhibition—collectively titled Art of Jazz: Form/Performance/Notes—is the result of harmonious partnerships between not only the Harvard Art Museums and the Cooper Gallery, but also Harvard art and architecture professor Suzanne Blier, visiting professor David Bindman, and Harvard students.

“There’s something delightful about all of the collaboration,” said Cooper Gallery director Vera Ingrid Grant, who curated the Notes segment of the exhibition. “The collective energy, generated by considering varying viewpoints, emanates throughout the show.”

Art of Jazz developed out of the class The Image of the Black in Western Art, co-taught by Blier and Bindman to graduate and undergraduate students. As part of the coursework, students engaged in object-based research using Harvard’s various art collections; jazz turned out to be a popular subject, and one that the professors realized would make for a fascinating exhibition. Thus, students were also able to learn from planning museum displays; they participated in everything from selecting objects to writing labels to organizing works within the galleries, said Suzanne Blier, the Allen Whitehill Clowes Professor of Fine Arts and of African and African American Studies.

Early on in the exhibition planning, Blier and Bindman sought to create a format that would span the Harvard Art Museums and Ethelbert Cooper Gallery. They decided to split the 70-plus objects into parts thematically, with the Cooper Gallery hosting the section that eventually was called Performance. Vera Grant, in turn, added a new section focused on contemporary responses (Notes).

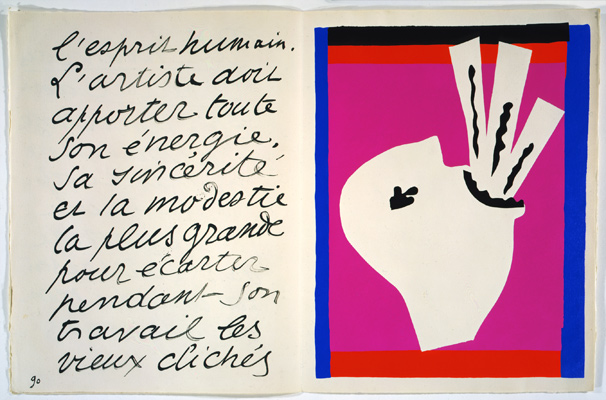

In Form, objects attest to the emergence of jazz in an array of artwork, and to jazz as a technique of creation. Featured works provide a diversity of form, media, and subject matter, from Viktor Schreckengost’s eye-catching “Jazz” Punch Bowl (1931) to Henri Matisse’s prints The Sword Swallower and The Clown from his book Jazz (1941), to Romare Bearden’s collage Soul History (1969).

In the Cooper Gallery, Performance offers a look at jazz as entertainment, through period visual cultural forms such as album covers (designed by Joseph Albers, Andy Warhol, and other artists), posters, and books. Evocative photographs capture musicians such as Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Duke Ellington at interesting and unexpected moments in their careers.

Notes rounds out the exhibition with paintings, photographs, prints, and mixed-media installations by contemporary artists, including Ming Smith, Whitfield Lovell, and Jason Moran (whose installation STAGED: Three Deuces mimics the close confines of a jazz club). “Notes is about how late 20th- and early 21st-century artists consider ‘jazz,’” Grant said. “Some of the works flip the script a little, playing with concepts such as gender, narrative, and gaze.”

While Form draws objects primarily from the Harvard Art Museums, Performance and Notes feature works from the Hutchins Center’s collection as well as a number of loans, including some from the archives of photographer Hugh Bell.

Mira Xenia Schwerda, a graduate student who took Blier and Bindman’s class in Fall 2015, discovered the relatively unknown Bell while poring through books on jazz. When Schwerda delved deeper into Bell’s oeuvre, she found that though the New Yorker had captured many jazz scenes, among other subjects, he had received only limited public and museum interest during his lifetime.

“I think we were very fortunate to come across this work,” said Schwerda, who helped arrange the loans of Bell’s photographs. “Hugh Bell wasn’t a musician himself, but he would go to the concerts and would socialize with some of these famous jazz musicians.” Bell’s nuanced black-and-white portraits—including a number of candid and emotional photographs of Billie Holiday backstage after a Carnegie Hall concert—make the most of his access and “give us a better understanding of New York jazz in the 1950s and 1960s,” Schwerda said.

Her findings, as well as the hands-on curation by all students who worked with Blier and Bindman, have made Art of Jazz especially meaningful. In a way, the collaborative aspects of the exhibition parallel the unifying aspects of jazz.

“Jazz is one of those extraordinary art forms that have brought people together” in economic, racial, global, and other contexts, said Blier. “I think in this rather complex world we’re living in today . . . there is something wonderful and transformative about artworks or art forms. In a certain sense, in celebrating the world of jazz, we’re speaking to that very fact.”