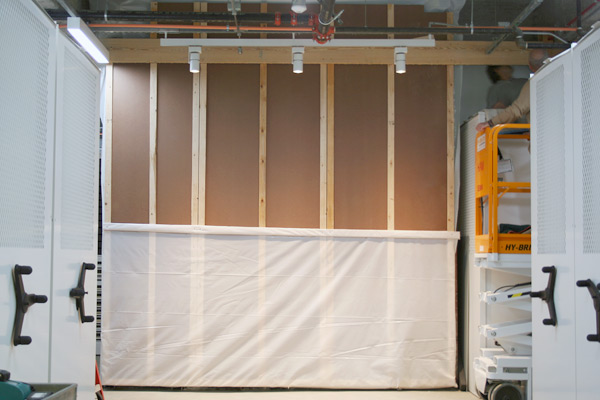

Structure, a large fresco created in 1934 and 1935 by social realist painter and Harvard graduate Lewis Rubenstein (Class of 1930), was unveiled once again just last month, as staff removed layers of protective material that had covered the fresco throughout much of the museums’ six-year renovation project. It was a welcome sight for conservators, including Teri Hensick, who had invested a great deal of time and energy in 2009 and 2010 to prepare Structure for this very moment. “I feel happy that the outcome is so great,” said Hensick, conservator of paintings for the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. Structure, like two other frescoes by Rubenstein at the Harvard Art Museums (The End of the World, after Signorelli and The Hunger March), is a true fresco—meaning it was painted directly onto the walls by applying dry pigments ground in water to specially prepared wet lime plaster. The fresco depicts the process of constructing the original Fogg Museum: workers are shown positioning steel girders, laying bricks, applying plaster, and painting a fresco. Along with the other Rubenstein frescoes, Structure was commissioned by the Fogg to give students the opportunity to learn about fresco painting techniques. (Preparatory sketches and other works by Rubenstein, along with his controversial 1937 murals in Adolphus Busch Hall, also comprise the artist’s many contributions to Harvard.) Because of the museums’ historic teaching mission, there was a great responsibility to protect the works inside the new Harvard Art Museums during the recent renovation—no simple task given that the project would require demolishing the walls around two of the three frescoes and moving them to new locations in the building. The first step in the process of preparing Structure for the move was to consolidate the upper fresco layers where the paint was becoming powdery with a special acrylic resin to prevent losses. Next, a large team including Hensick and Tony Sigel, conservator of objects and sculpture, applied numerous coats of the waxy organic compound cyclododecane to build a 3/8-inch-thick layer on top of the fresco, to further guard against damage during the relocation. Next, the conservators covered the coated fresco with an air barrier to seal it. Years later, after completion of the renovation, when Structure would again be exposed to circulating air, the cyclododecane would simply sublimate, or change from a solid to a gas, leaving the original fresco seemingly untouched. Workers from Skanska, the company that managed the construction project, were extremely careful in cutting free and moving Structure from the surrounding wall; adding a steel frame, they bundled it in protective foam and plywood, with vibration monitors inside to allow conservators to keep tabs on it over the years. To honor Structure’s past, engineers decided to leave exposed one edge of the original brick wall on which the fresco had been painted. Finally, in January, about five years after the cyclododecane was applied and two years after it had largely sublimated, Structure was again uncovered. Senior collections specialist Jon Roll, collections specialist Sean Lunsford, and museum installer/art handler Chris Minot removed the plywood, foam, and other layers as conservators (and a few curious museum staffers) watched. Some small patches of cyclododecane remain on the fresco’s surface, but within a few months the substance will be completely gone, and Structure will look as if it had never been moved. “Even though we faced challenges throughout, it’s really gratifying to see the fresco in its new home,” said Hensick.

Unveiling Structure

March 10, 2015