In recent weeks at the Harvard Art Museums Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, a team of scientists, conservators, and a curator has been putting Houghton Library’s 15th-century illuminated manuscript Emerson-White Book of Hours (MS Typ 443–443.1) under a microscope. They hope to ascertain the book’s material composition and to learn more about the techniques the artists used when they created it, which will add crucial data to the existing body of research.

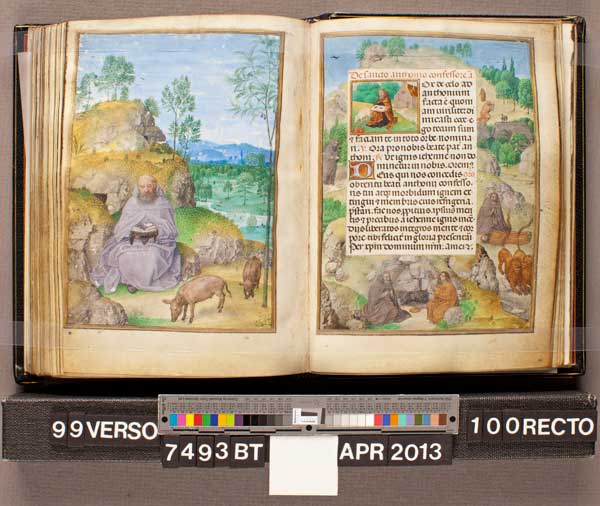

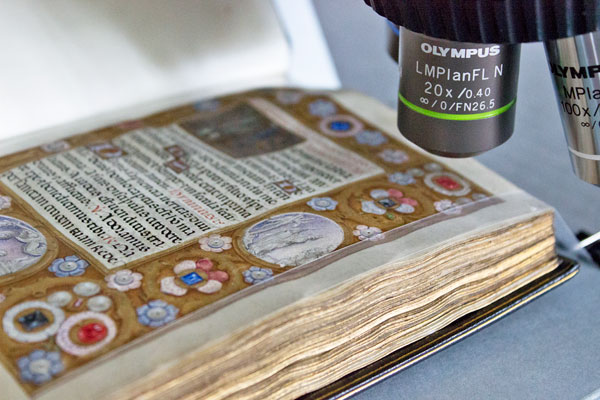

The parchment pages of this petite two-volume prayer book measure just 15 centimeters tall and are made from extraordinarily thin and finely prepared animal skin, probably from a young calf. The phenomenal paintings contained within include lush, full-page landscape scenes, like that of Saint Anthony the Abbot in the Egyptian wilderness, and elaborately decorated borders with colorful insects and flowers that frame Christian devotional texts. The paintings are so carefully detailed it is thought that the artists sometimes used paintbrushes consisting of a single hair. Under magnification, it’s possible to see the application of a solitary dot of paint on the tip of Saint Anthony’s companion’s nose (see image above).

The elaborately illuminated manuscript provides a fascinating record of medieval painting, making it a valuable resource for students and scholars of art history and theology. That is why Hope Mayo, Philip Hofer Curator of Printing and Graphic Arts at Harvard’s Houghton Library, is now working with conservators (including two former Straus Center conservation Fellows Debora Mayer and Theresa Smith) from the Harvard Library’s Weissman Preservation Center to complete a consolidation treatment on the fragile book, which will help prevent further losses to the paint from handling.

Mayo and the Weissman conservators knew that this was an excellent opportunity to also perform a technical analysis on the book. Enter our Straus Center. As the only scientific laboratory on campus dedicated to working on cultural heritage objects, the center is sometimes called upon to collaborate with various university constituents, adding great understanding to the distinctive works cared for by Harvard.

With Mayo, the Weissman conservators identified for the Straus Center which pages of the Emerson-White Book of Hours they wanted analyzed. They hoped to answer questions about pigment choice, color mixing, and technique of application, found, for example, on the full-page illuminations attributed to the Master of the Houghton Miniatures. Senior scientist Katherine Eremin; Georgina Rayner, Andrew W. Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Conservation Science; and guest conservation scientist Erin Mysak got to work.

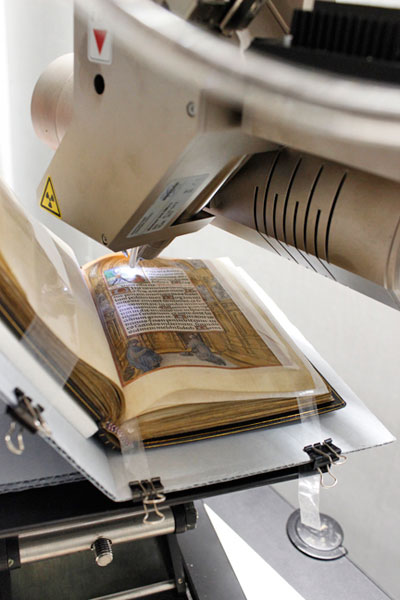

Mysak, with the support of Straus Center scientists, used three complementary, nondestructive techniques—Raman spectroscopy, X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy, and infrared photography—to analyze thirty pages from the two volumes, taking hundreds of individual spectroscopic measurements. The first two techniques enabled Mysak to identify the pigments found in the manuscript’s paintings and the minerals used to make them. Infrared photography captured traces of the drawings that guided the illuminators in their work. In a thick binder containing magnified photographs of the manuscript’s pages, Mayo and the Weissman conservators kept detailed notes that mapped where analysis was needed, completed, and the results of the testing.

The Straus group verified that many pages of the Emerson-White Book of Hours featured some of the most precious materials available at the time, such as shell gold and natural ultramarine blue—a pigment made from the mineral lapis lazuli that was imported from Afghanistan and was at the time considered more precious than gold. The group also identified numerous additional mineral pigments, which are generally more resistant to fading.

These kinds of details give researchers a better understanding of the time and expense invested in the Emerson-White Book of Hours as well as factual information about the original creation of the manuscript in the 15th century. As the book was painted by multiple artists and had multiple owners (the manuscript contains an Italian inscription and a Spanish prayer), the findings from the Straus Center’s technical analysis will provide clues to the book’s complex history, helping art historians build on what is already known of the manuscript’s provenance and attribution.

Just as this Book of Hours was created by a specialized group of artists, it seems fitting that this manuscript is now receiving treatment and technical analysis by a team of specialists in the 21st century. The cross-Harvard effort to treat and analyze this work is a stellar example of the complementary resources and expertise available on campus. This rich collaboration has invigorated the study of this extraordinary work and ensured that the manuscript will remain accessible for future use by students and scholars at the university.

The Emerson-White Book of Hours will soon be available for class use at Harvard University, digitized for electronic access, and featured in an exhibition of illuminated manuscripts that is slated for 2016.