Just a few weeks ago, an international team of archaeologists, architects, conservators, scholars, and other students and specialists arrived in a village in western Turkey to continue excavating the ancient Lydian city buried there. Since 1958, the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis—a collaborative research and educational project sponsored by the Harvard Art Museums and Cornell University—has organized an annual archaeological expedition to better understand the impressive history of the site, which has existed for more than 3,000 years. Founded by George M.A. Hanfmann, then professor of fine arts at Harvard University and curator of classical art at the Fogg Museum; and Henry Detweiler, professor of architecture at Cornell University, the exploration was inspired by earlier 20th-century digs that had left many unanswered questions about the site’s origins.

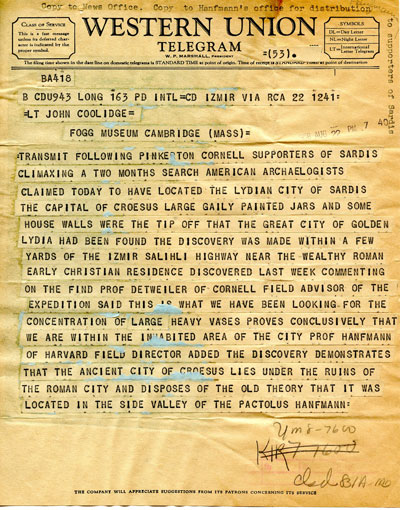

In that first season in the field, in 1958, the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis sent John Coolidge, director of the Fogg Museum, an enthusiastic telegram detailing the discovery of the Lydian-period city of Sardis, then thought to lay underneath Roman buildings. The message relays how, after two months of searching, “American archaeologists claimed today to have located the Lydian city of Sardis the capital of Croesus,” and that “large gaily painted jars and some house walls were the tip off that the great city of golden Lydia had been found.”

Sardis was built on the edge of a fertile plain in the Hermus Valley at the base of Mount Tmolus. As the capital of the Lydian empire (8th–6th centuries BCE), Sardis was one of the major cities of Asia Minor and thrived under the rule of King Croesus, before falling to the Persians in the mid-6th century BCE. During this period the Lydians learned to separate gold and silver from alluvial gold and minted the first bimetallic coins in gold and silver. Archaeological highlights from this period include the royal burial mounds at Bin Tepe, the Lydian fortification wall, Lydian houses, and the gold-refining area. Important Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine monuments include the temple of Artemis, a bath-gymnasium complex, a synagogue (the largest of antiquity), villas, and a row of shops adjoining the synagogue.

Since its inception, the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis has inventoried more than 13,000 objects and saved thousands more for future study. The Harvard Art Museums remain the administrative headquarters, archives, and publications program for the exploration, which is currently directed by Nicholas D. Cahill of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Although it’s been decades since the Sardis team has communicated with us via telegram during their summer abroad, the museums continue to receive exciting dispatches that detail the discoveries found at the site. This year will be no exception, so check back later this summer for stories fresh from Sardis’s ancient soil.