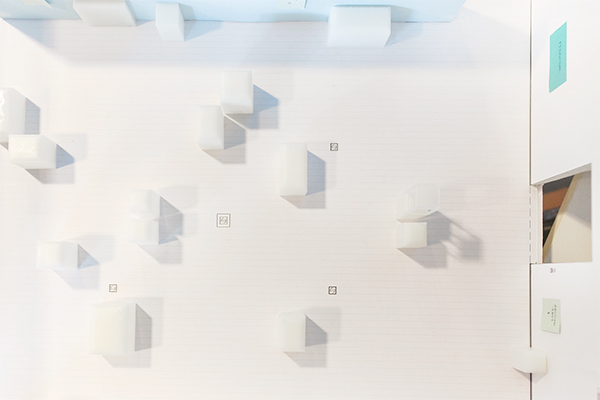

In planning for the upcoming special exhibition Animal-Shaped Vessels from the Ancient World: Feasting with Gods, Heroes, and Kings, curator Susanne Ebbinghaus and exhibition designer Justin Lee spent time developing two- and three-dimensional plans for the gallery spaces. One step involved constructing a model with miniature mock-ups of some of the art and casework. But with much of this exhibition made up of 3D objects, a challenge loomed: how to best create the miniature cases for the gallery model?

Typically, miniature cases are assembled by hand with paper, Styrofoam, or wood—a laborious process. This time, however, a more efficient technique was proposed: creating them with precisely scaled-down measurements using the new desktop stereolithography (SLA) printer in the Department of Digital Infrastructure and Emerging Technology (DIET).

Technology fellow Gavriella Levy Haskell, who took the lead on the project, first had to get to know the printer itself. “I hadn’t had any experience with 3D printers, so I wasn’t sure what to expect,” said Levy Haskell. “But as I started doing research on how to operate it, I got pretty excited. It’s not very hard to use and it works really well.”

The Printing Process

Equipped with computer files of scaled-down versions of the cases that Lee had supplied, Levy Haskell prepared the forms for printing using a 3D modeling program. Due to the miniature cases’ small size (just a few inches tall, at most), she was able to print them in batches.

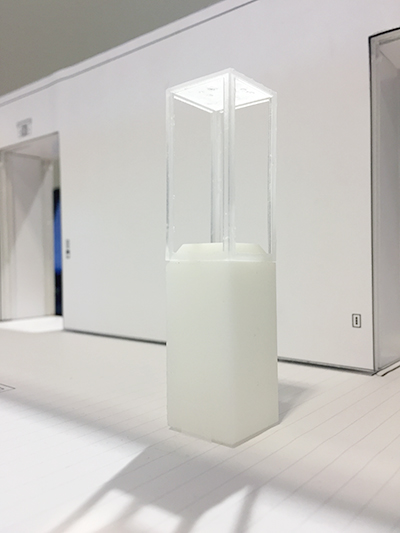

The printer uses a chemical process to create objects atop unique support scaffolding. A laser shines through the clear bottom of a tank filled with photosensitive liquid resin to solidify the resin where the object will be. Then the platform supporting the tank is raised a few millimeters, and the process is repeated for each layer of the object. It’s a slow process—Levy Haskell’s largest batch took 11 hours to print—but it results in very sturdy products.

Upon completion of printing, the objects harden with exposure to UV light and are removed from the scaffolding and cleaned with isopropyl alcohol. Then, it takes a day or two for the pieces to fully dry before finishing touches can be made.