Contemporary German artist Wolfgang Tillmans’s Folding, Refraction, Touch—Installation for the Busch-Reisinger Museum—which explores the photographic medium and its materiality—is a major recent acquisition for the Harvard Art Museums.

It also provides a powerful theoretical framework for the new exhibition Folding, Refraction, Touch: Modern and Contemporary Art in Dialogue with Wolfgang Tillmans (August 27, 2016–January 8, 2017). The shared words “folding,” “refraction,” and “touch” resonate not only in Tillmans’s installation, but also in works on display alongside it, by such artists as Oskar Nerlinger, Norbert Kricke, and Isa Genzken.

“We want viewers to look at the exhibition and ask themselves, how could these terms apply?” said Lynette Roth, the Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum and acting head of the Division of Modern and Contemporary Art. Roth curated the show with the help of Olivia Crough, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard. The two have created an exhibition that offers a meditation on concepts of light, surface, abstraction, and the body, evident in the use of folded materials, refracted light, or of implied physical acts, such as pressing and pulling.

Tillmans’s Installation

Like a number of other important international contemporary artists featured at the museums (including Rebecca Horn), Tillmans engages with a diverse range of media, including photography, installation, film, and music.

“My aim has never been to be a photographer,” Tillmans said recently in a phone interview. “But I arrived at photography after I had worked with other media. I realized it does everything I need to do [as an artist].” Through photography—as well as photographic processes and materials used in nontraditional ways—Tillmans explores the different qualities inherent in the medium. While his work continually explores abstraction and materiality, it is also often politically and socially charged (a recent example was a series of posters he made urging against voting for Brexit).

Tillmans commonly references or recombines his past oeuvre, investigating relationships between various images. He employs that technique in Folding, Refraction, Touch—Installation for the Busch-Reisinger Museum, which includes 19 components spanning three decades of the artist’s career. He said the individual images weren’t chosen with a particular thesis or narrative in mind (in fact, he decided on the title only after the installation was complete); however, “very early on it emerged that I was interested in thematizing the object of the photograph, as well as our relationship to surfaces, to the visual world as we experience it through our eyes, in both a sensual and conceptual way,” to the interconnectedness of object, surface, texture, and visual pleasure, as he described it. That framework led him to select examples from his Kopierer (Copier) and Paper Drops series, which highlight the physicality of materials involved in creating images.

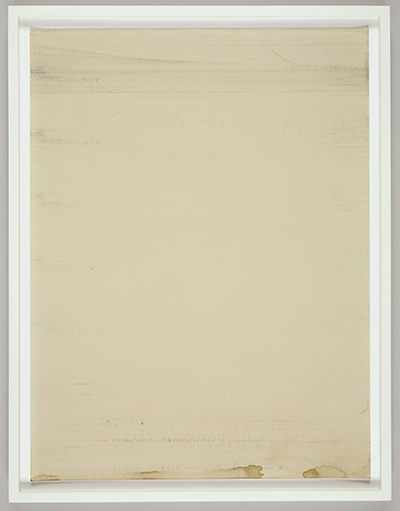

Silver 101 (2012), an exploration of camera-less photography, is another example. The image is a chromogenic print made by passing undeveloped photographic paper through a dirty print processor, a unique sort of physical contact that lends the paper a distinctive, abstract pattern. While the original work is displayed in the exhibition, a digitized and enlarged version originating from the same source is part of Tillmans’s installation.

The artist’s inclusion of some of his early photos of German subjects is “a nod to the fact that the installation is [part of the collection of] the Busch-Reisinger Museum,” which is dedicated to the art of German-speaking countries. These works include U-Bahn sitz (1995), featuring refracted light upon bowed subway seats upholstered in an anti-graffiti pattern; Klassenraum, Leibniz Gymnasium I (1991), depicting empty desks in a classroom in Tillmans’s old school; and Love Parade, rain (1992), a photograph from his iconic imagery of the then-burgeoning techno scene in Germany.

The range of sizes of the works in the installation (from postcard-size to larger-than-life), as well as their mounting (some are framed, while others are simply taped or clipped to the wall), underscore their materiality. Such diversity lends the installation a “playful feel,” but one that is, Roth said, “carefully dictated by the artist.”

For Crough, that approach prompts consideration of an image’s uniqueness. “His installation shows the tension of a photograph as both something that can be infinitely reproduced but also, in a sense, can’t be,” she said. “An individual photograph has a longevity, a power, but at the same time, because it is printed on paper it’s very vulnerable.”

Dialogue Partners

As the exhibition title makes clear, the work of other artists is placed in dialogue with Tillmans’s installation. Among them are individuals who experimented with the photogram, including Oskar Nerlinger, who in the 1920s layered paper and tissue atop undeveloped photographic paper to create what he called a “peculiar magical effect.”

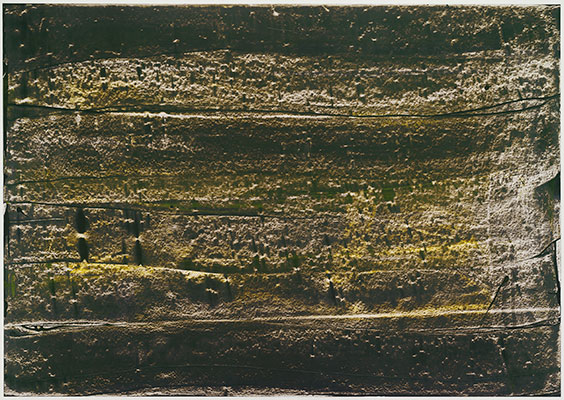

Isa Genzken’s painting Basic Research (1989) also draws attention to the physicality of artistic practice. Genzken made the abstract work using a squeegee; she rubbed oil paints across paper laid on the floor of her studio, imparting an uneven texture that evokes the depth and spatiality of a photograph.

Sculpture also contributes to the conversation. Norbert Kricke’s Space Sculpture (c. 1960), for instance, conveys a sense of lightness and balance through twisted, bent, and hand-pulled bundles of metal wire. Similarly, 61/6 (1961), by the artist couple Brigitte and Martin Matschinsky-Denninghoff, displays both concavity and convexity through its open form and dynamic folds of thin, soldered brass rods. “These works move the idea of refraction beyond the two-dimensional realm,” Roth said.

Like all art in the show, the varied objects also underscore the museums’ deep modern and contemporary holdings. “In many ways, this is an exhibition about our collection,” Roth said. “With Tillmans’s installation, we are showcasing a major acquisition of contemporary art—and this is the very first time anyone will see it. It’s an exciting moment. But we are also pleased to be able to present aspects of our collection that haven’t received as much recent attention, in the hope of expanding the conversation around Tillmans’s work.”