Editor’s note: Every summer, an international team from the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, sponsored by Harvard and Cornell Universities, visits Turkey to work on the ongoing excavation of the site. As the Sardis staff here at the Harvard Art Museums gear up for another season, field director Nicholas Cahill describes some findings made in the area believed to be the palace of the legendary Lydian king Croesus.

Sardis, in western Turkey, is most famous for being the home of the Lydian kings—the richest and most powerful rulers that the Greeks knew. These kings, who reached the height of power during the 7th and 6th centuries BCE, had close relations with their Greek neighbors. King Croesus, in particular, figures prominently in Greek legends, in which Greeks visit the king’s palace.

One such story is about the Athenian statesman Solon visiting Croesus. As the king led Solon through his palace and showed him the riches in his treasury, he asked the statesman who was the happiest and most prosperous man in the world. Solon named a series of ordinary Greeks, who had died with public acclaim but with only middling wealth. He further explained: “You seem to be very wealthy, but I cannot tell you the answer you ask for until I learn how you have ended your life. For many wealthy people are unhappy, while many others who have more modest resources are fortunate.”

The Athenian Alcmaeon also visited Croesus and was also led by the king through the palace. As a gift, Croesus offered him as much gold dust from the treasury as his guest could carry. Alcmaeon had special clothing made that would allow him to store the dust. After pocketing the dust away in his clothing, he waddled so amusingly that Croesus gave him twice as much, establishing the fortunes of this aristocratic family.

Recent excavations at Sardis have probably located the palace buildings of Croesus and other Lydian kings, set on high terraces that enclosed hills in the center of the Lydian city. The gold is long gone, of course, and the buildings atop these terraces have been ransacked and almost completely destroyed by later inhabitants, perhaps because even the walls were made from fine stone that could be reused. But blocks of beautifully finished marble and limestone, artifacts from the hills, and the monumental terraces suggest that this was an elite region of the city, separated from and raised above the lower town.

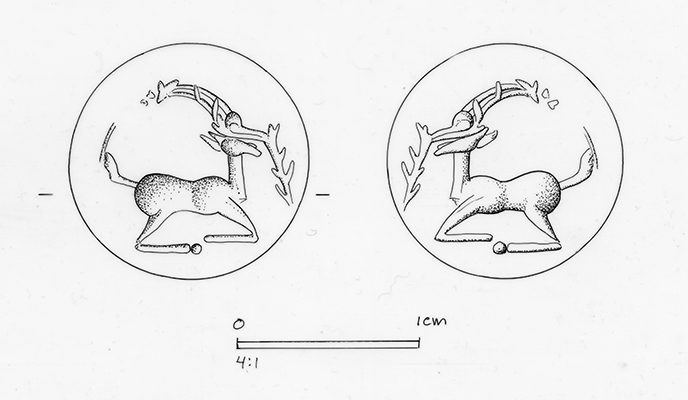

In 2012, a fragment of an ivory inlay was found in the area. It probably depicts Artemis, the Mistress of the Animals; she holds two lions by their tails. It may have belonged to a piece of luxury furniture and is similar to the much more numerous and complete ivories found at Nimrud in Iraq, by Max Mallowan (and cleaned by his first wife, Agatha Christie). Hundreds of fragments of colorful jasper from the Lydians’ time are perhaps working chips from an atelier for making stone tableware, which was a favorite of the Persian kings. The buildings were decorated with colorful molded and painted terracotta roof tiles and revetments, depicting the winged horse Pegasus, chariots, and other motifs. In 2011, a jasper sealstone turned up—the first such found by the current Sardis expedition.

Although the early remains have been thoroughly plundered, we have found human bones from at least two individuals, and dozens of arrowheads, perhaps from 547 BCE, when Cyrus the Great of Persia captured Sardis and burned the city. Upon this sudden change in fortune, Croesus is said to have recalled Solon’s advice and finally realized the wisdom of this philosopher.

Nicholas Cahill is field director at the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis and professor of art history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.