Just around the corner from the renowned Forbes Pigment Collection in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies sits an unassuming, unsung hero of conservators and conservation scientists.

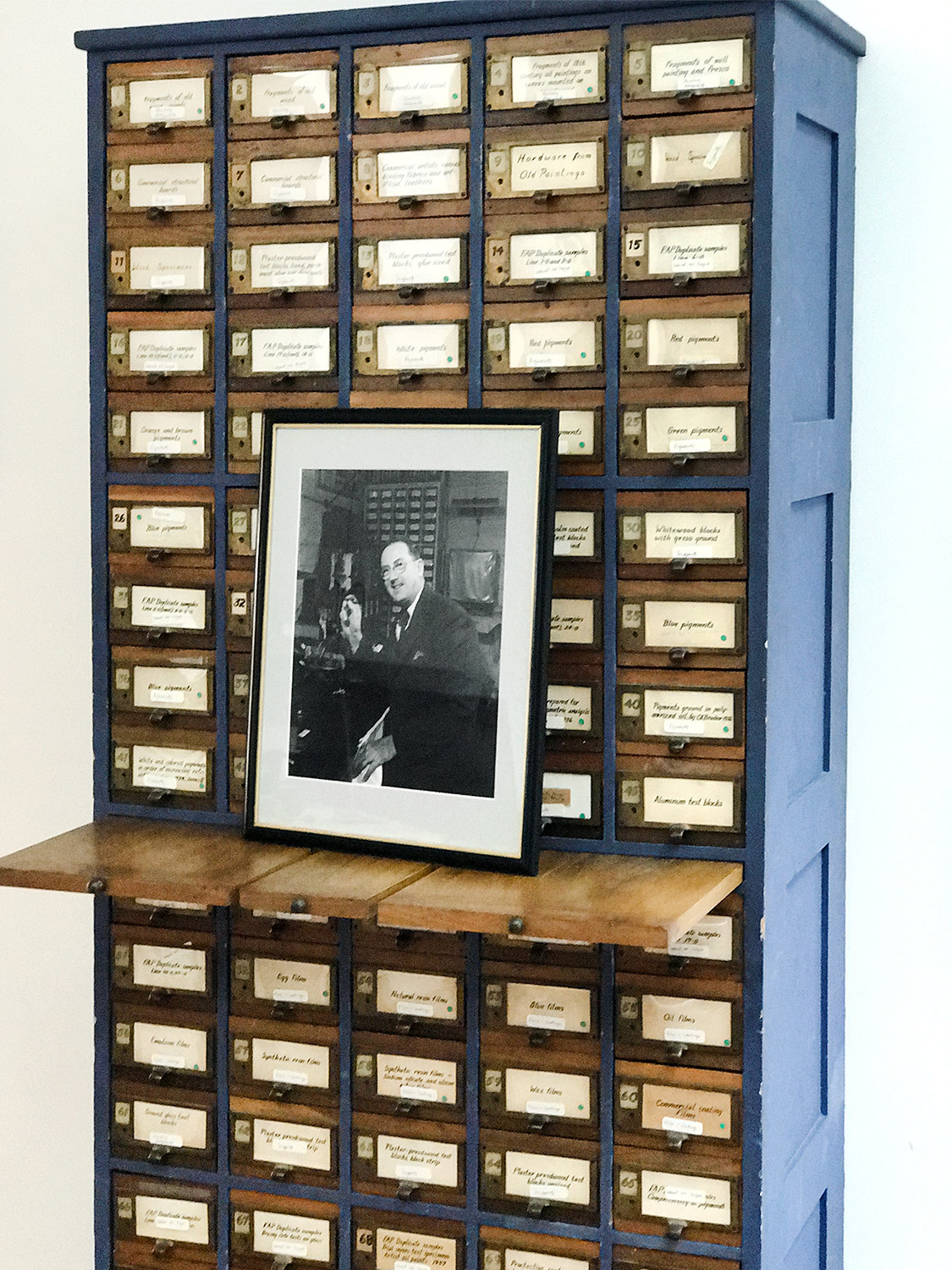

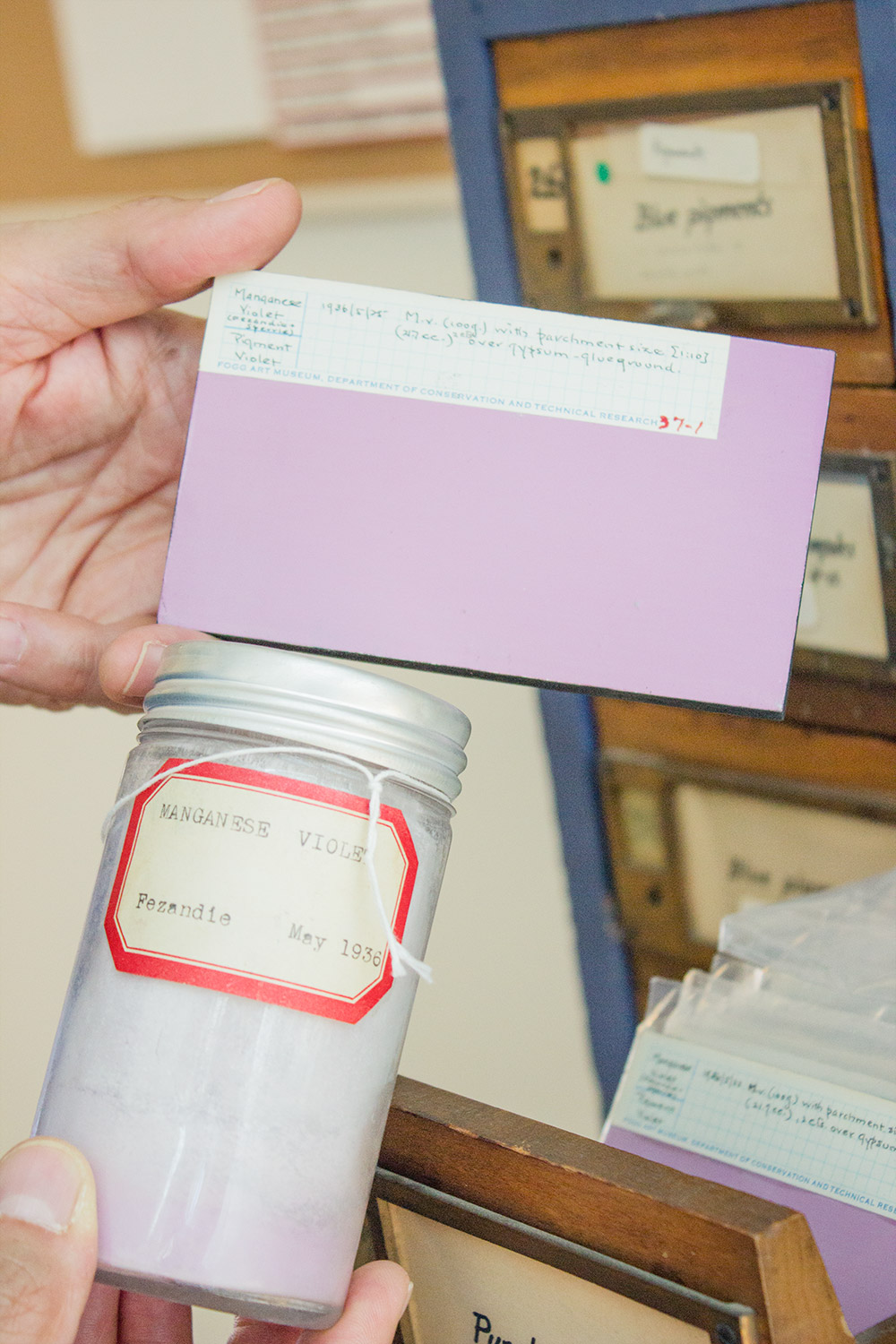

The Gettens Cabinet, created in the 1930s, stands over 6 feet tall, with 85 drawers. It looks a bit like a library card catalogue in appearance, but the contents include sample materials such as “Blue Pigments,” “Wood Specimens,” and “Gas Exposed Paint.”

The cabinet is named after Rutherford John Gettens (1900–1974), the Fogg Museum’s first chemist (and, in fact, the first scientist at any museum in the United States). Gettens and his team of conservators compiled this important resource at a time when conservation science was just emerging as a field. The idea of applying scientific methods to the study of art and art history was relatively new, and the cabinet demonstrated the principles and practices of a budding discipline.