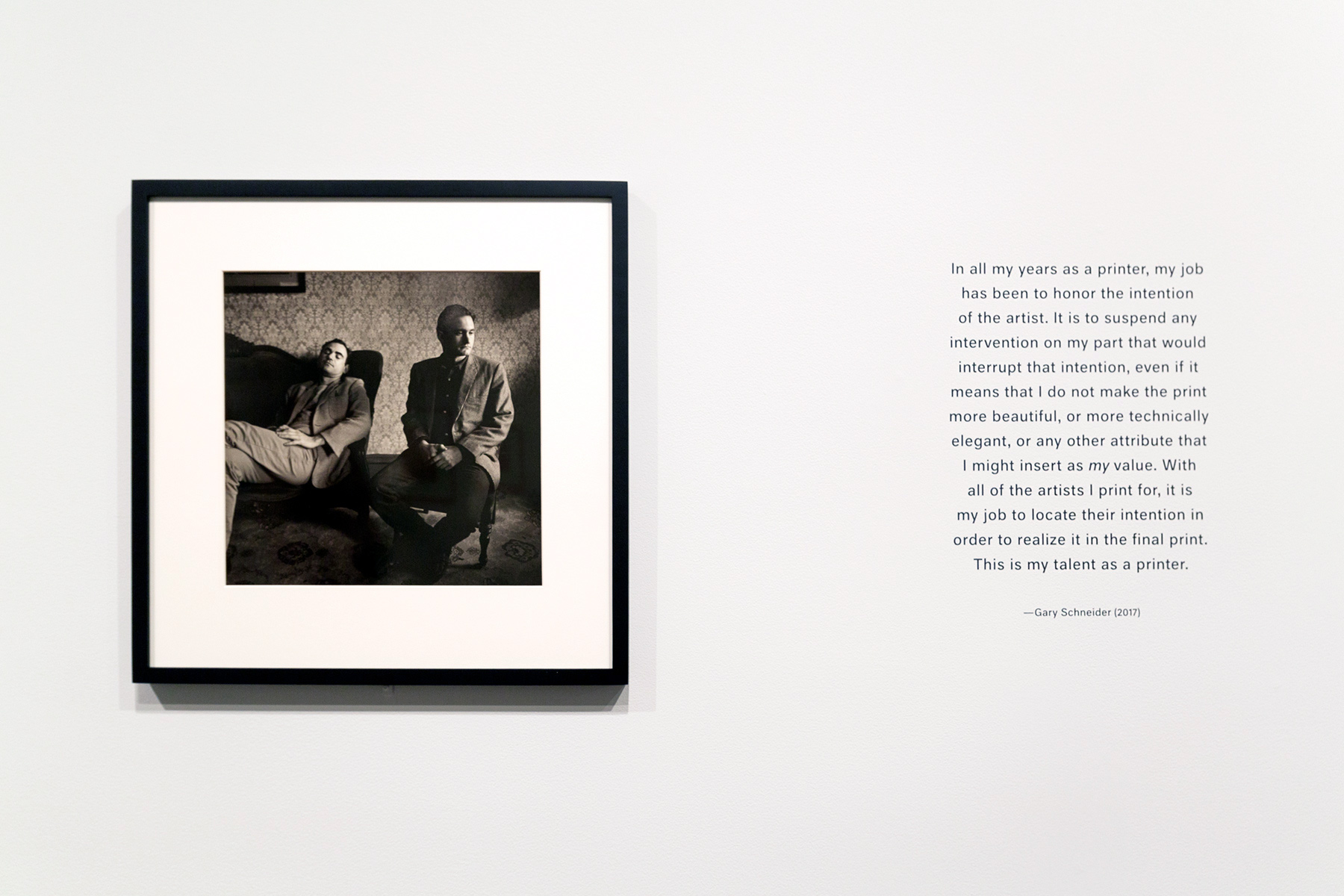

The masterful work of a photographic printer and the dozens of artists with whom he collaborated is represented in this summer’s exhibition Analog Culture: Printer’s Proofs from the Schneider/Erdman Photography Lab, 1981–2001. And as staff organized the exhibition and related programming, another form of collaboration was front and center.

Curated and led by Jennifer Quick, the John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Associate Research Curator in Photography, the project was supported by the museums’ hardworking staff but also by three Agnes Mongan Curatorial Interns, brought on specifically to help develop aspects of the exhibition.

Over the last two years, graduate students Jessica Bardsley, Davida Fernandez-Barkan, and Jessica Williams conducted foundational research for the exhibition, wrote for the online Special Collection and the exhibition’s accompanying book, produced gallery text, and helped plan events and film screenings as well as the related Lightbox Gallery installation A.K. Burns: Survivor’s Remorse.

“All three students were essential colleagues for the project,” Quick said. “Each drew upon her own areas of expertise to make important and unique contributions to the exhibition.”

As the first of the three interns to work on the exhibition, Williams helped envision the shape and content of the digital resource The Schneider/Erdman Printer’s Proof Collection, an online repository for the approximately 450 prints and associated materials that inspired and informed Analog Culture. With Quick, she conducted multiple interviews with Gary Schneider and John Erdman about their experiences working in the photography lab they operated from the 1980s to the early 2000s. Fernandez-Barkan also contributed to this work; she and Bardsley later assisted in building the digital resource.

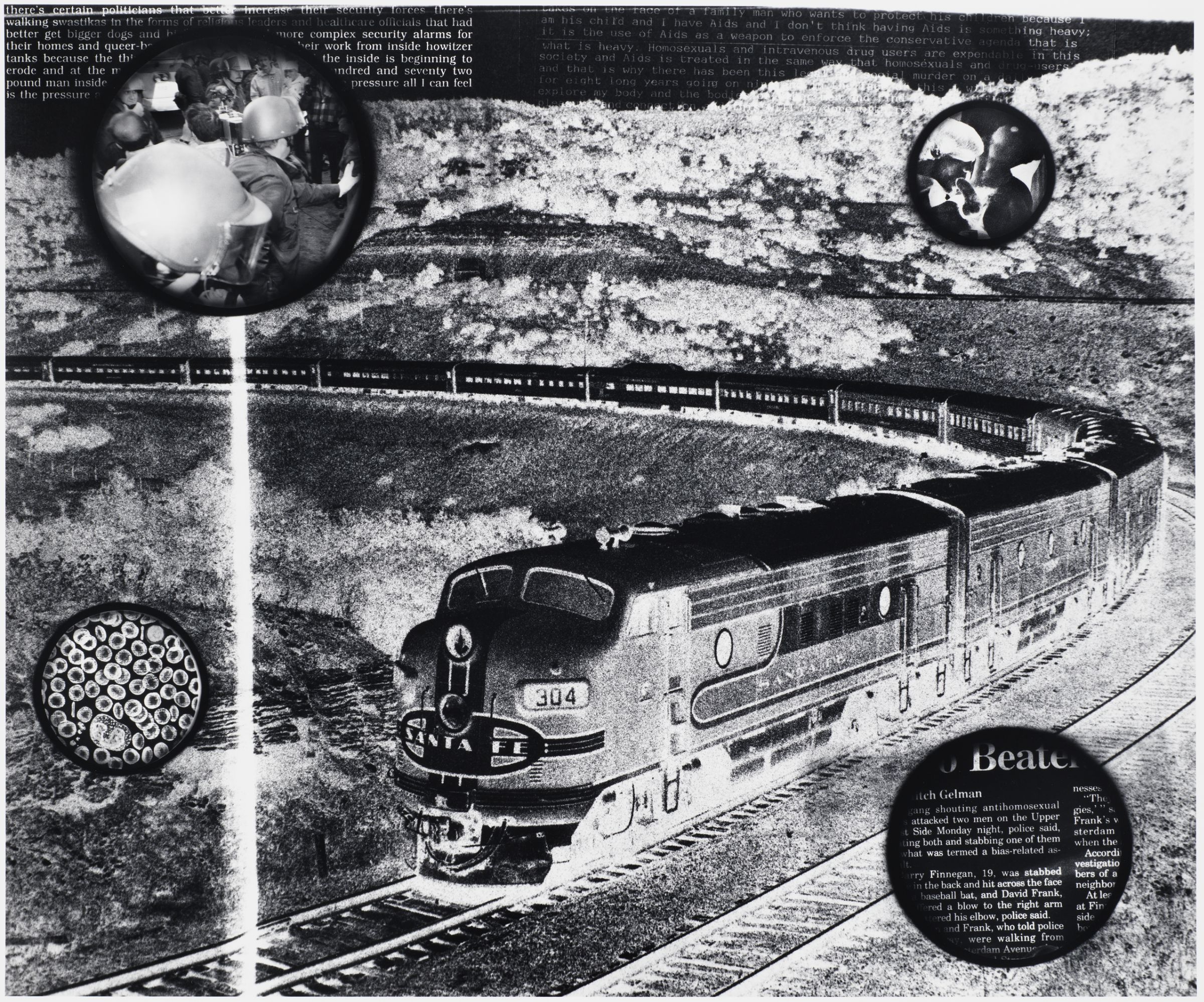

The team organized the online collection around ten case studies, each of which shares a story behind a specific image or group of images. “We tried to select prints that would be most compelling for both a general audience and historians,” said Williams, a Ph.D. candidate in the history of art and architecture at Harvard. “The case studies describe a particular process or challenge that Gary and John came up against, as well as personal stories about relationships they had with photographers.” The case studies also touch on moments of social and cultural change, such as the AIDS crisis and the transformation of New York’s urban landscape, that were taking place when particular prints were made.

Many case studies include original video interviews with Quick and Schneider. For instance, in one video, related to Peter Hujar’s Will (1985), Schneider explains to Quick how he first met Hujar and the story behind the print of Hujar’s iconic image.

Quick, Williams, and Fernandez-Barkan also ensured that the digital resource covered the technical processes Schneider and Erdman used to produce the prints. It’s a topic that will likely prove enlightening to a new generation of viewers.

“When we talk about photography and photo history, it can get bogged down in jargon,” Williams said. “We wanted to make the online collection exciting and accessible even for people who don’t know anything about analog photography.”

Drawing upon her research for the digital resource, Williams also contributed an essay to the Analog Culture publication. The book provides an in-depth look at the technical, material, and interpersonal intricacies of Schneider and Erdman’s photography lab. Williams’s essay discusses the idea of translation in photographic printing and covers a number of important prints, including Hujar’s Will, David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (Buffalo), and images from Wojnarowicz’s Sex Series.