More than three decades after his death, James Baldwin remains one of the most well-known voices in American cultural criticism. A prolific writer, Baldwin addressed issues of race, inequality, sexuality, violence, family, and personal transformation in 20th-century America, among other subjects.

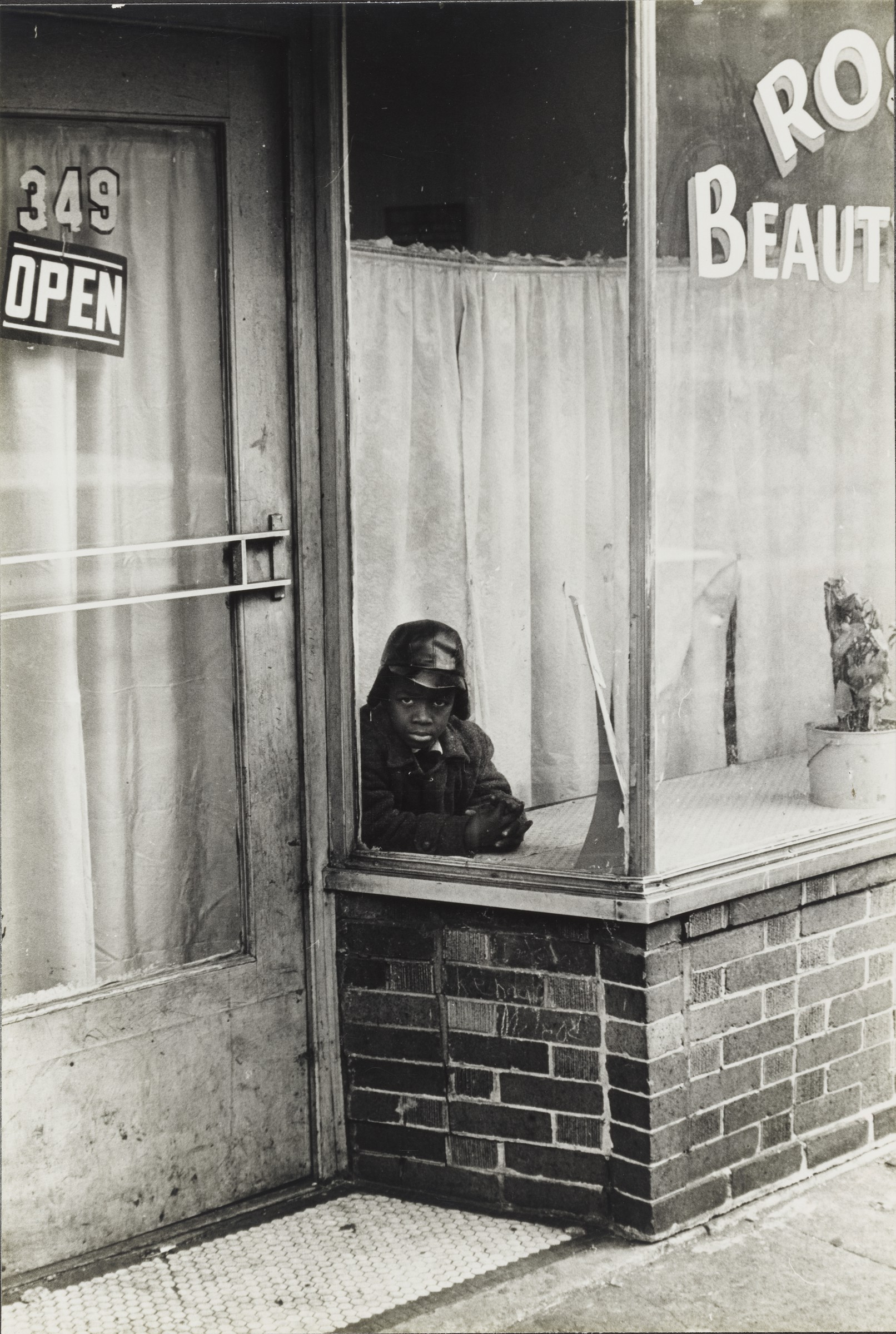

Time is Now: Photography and Social Change in James Baldwin’s America(September 13–December 30, 2018), a new special exhibition at Harvard’s Carpenter Center for Visual Arts, celebrates and expands the conversation around Baldwin’s formidable legacy, with a selection of approximately 30 photographs taken during the writer’s lifetime. It also complements Teresita Fernández’s public art installation in Harvard Yard this fall, which references Baldwin's essay Nothing Personal, which was published in 1964 as a collaborative book with photographer Richard Avedon.

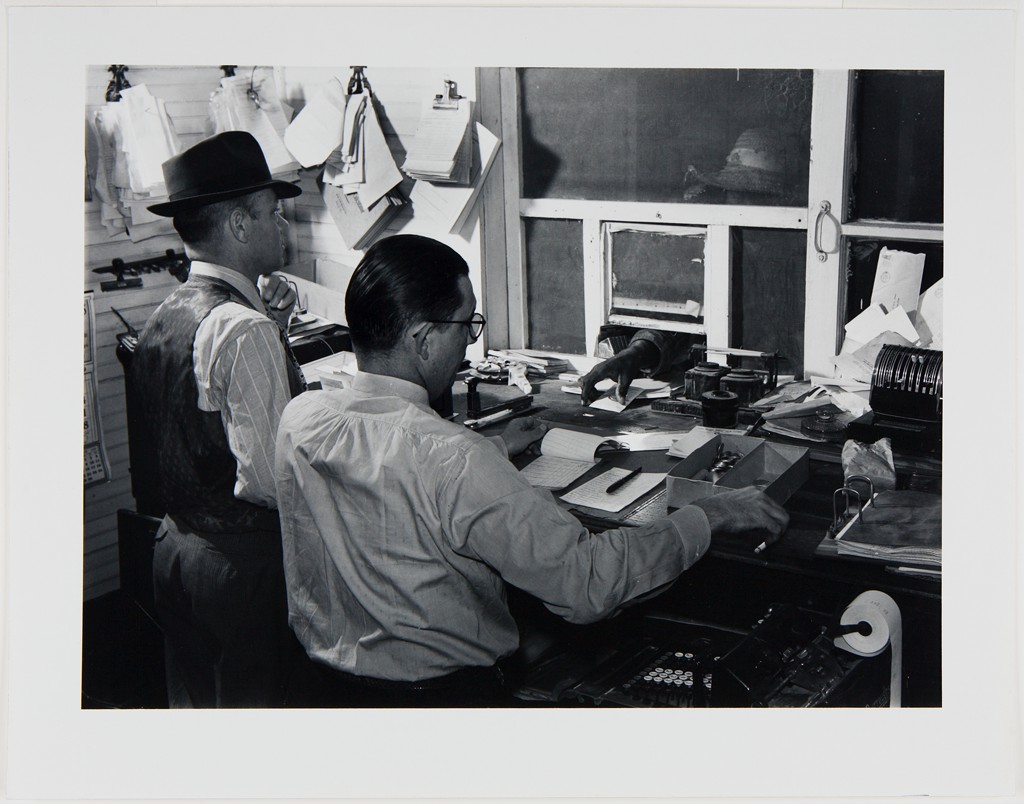

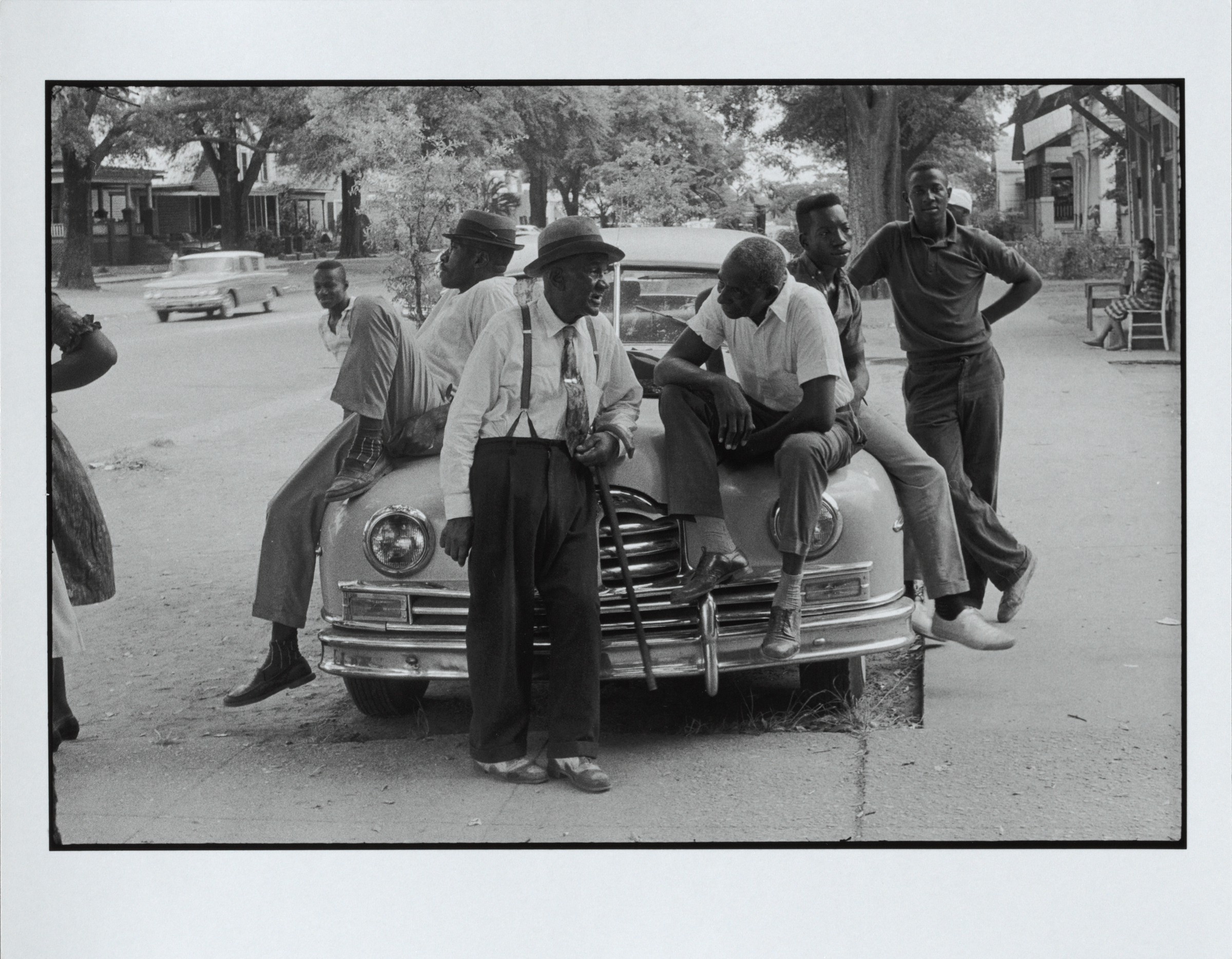

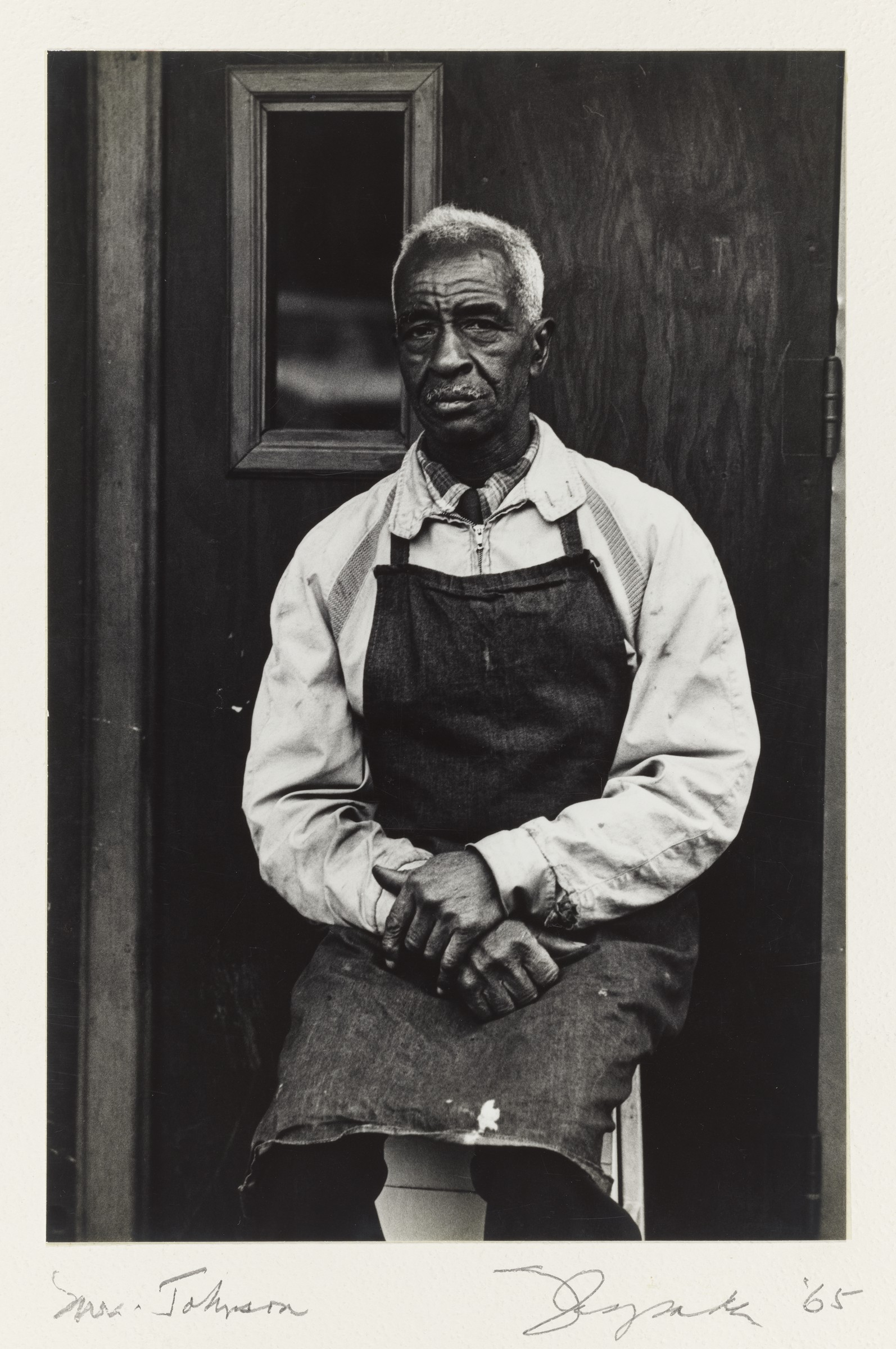

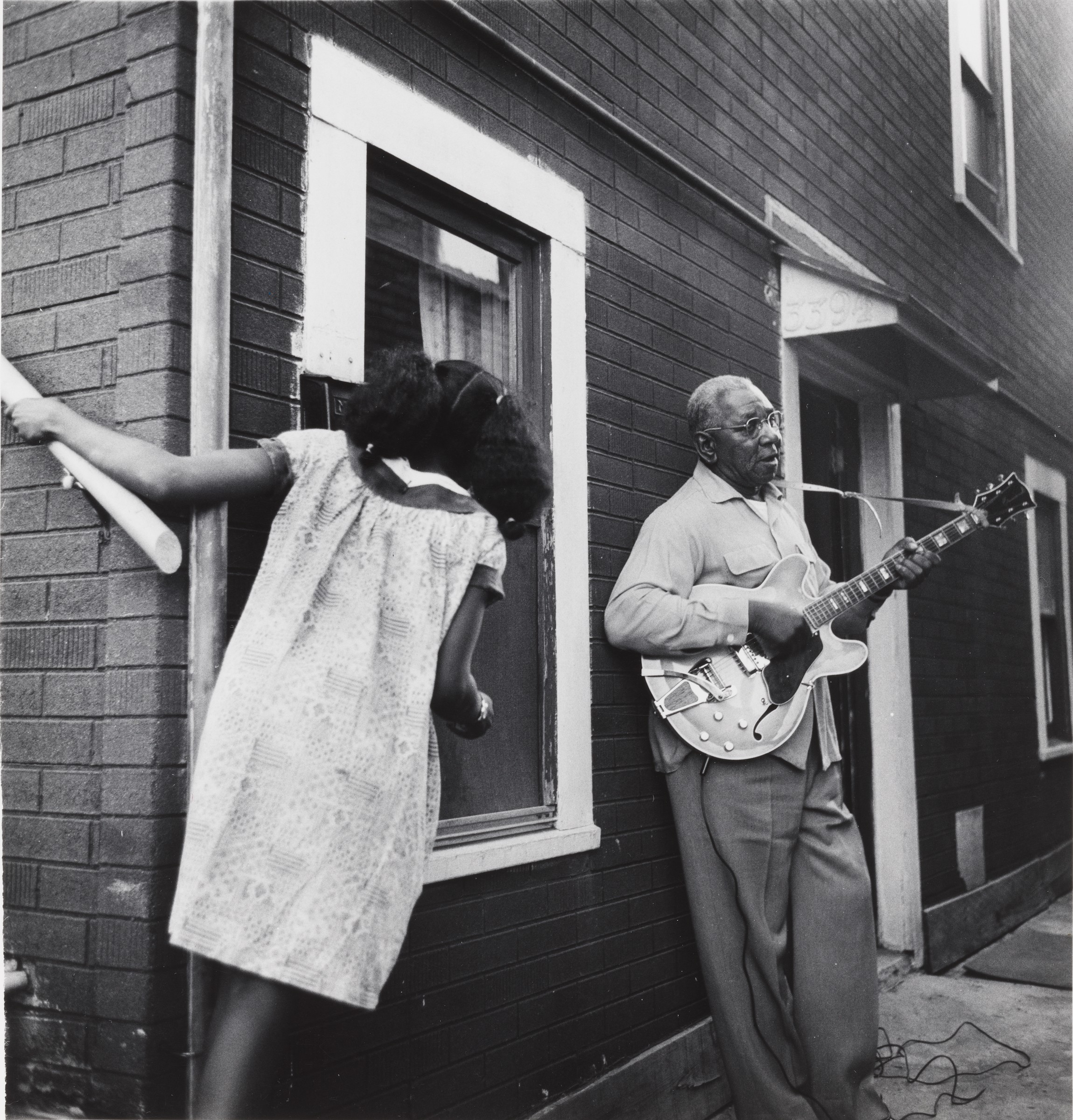

Time is Now is organized chronologically and centered on themes related to Baldwin’s life and times; it features a multi-generational set of documentary photographers, including Diane Arbus, Dawoud Bey, Frank Espada, Robert Frank, Joanne Leonard, Danny Lyon, Ben Shahn, John Simmons, and Marion Post Wolcott. All of the photographs are drawn from the Harvard Art Museums’ permanent photography collection, which was significantly strengthened in 2002 when the Carpenter Center transferred its renowned teaching collection of more than 10,000 prints, 40,000 negatives, and related materials to the museums. A number of the images in the exhibition are recent acquisitions, and most photographs have never been shown at the museums. Time is Now represents the latest in a series of collaborations between the two institutions.

We asked exhibition curator Makeda Best, the Harvard Art Museums’ Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography, to tell us more about the exhibition and the photographs she selected for display.

Index: What makes James Baldwin’s life and career such enduring subjects for study and reflection?

Makeda Best: There is a great deal of scholarship on Baldwin, and a persistent theme that I noticed in my research for this exhibition and in popular writing about him is the ways in which America hides from its past. He articulated a lot of the hypocrisies and ironies in American culture, which continue to be relevant. His ideas about America not living up to its true potential and his criticism of American life and history—those things have always resonated with people.

His very deeply reflective personal journey—as a man and as a gay man—and his thoughts about the artist’s role in society are also still relevant today.