American art historian Bernard Berenson is usually remembered as a connoisseur of Italian Renaissance painting. But a new exhibition this summer promises to broaden our understanding of Berenson’s collecting and art interests. A New Light on Bernard Berenson: Persian Paintings from Villa I Tatti (May 20–August 13, 2017) focuses on Berenson’s love of illustrated Persian manuscripts.

“Early 20th-century art collectors like Berenson were excited about Islamic art, which received attention for its bold colors and attractive designs,” said exhibition organizer Ayşin Yoltar-Yıldırım, who is assistant curator for Islamic and later Indian art at the Harvard Art Museums. “The early 1900s was also a time when many illustrated Persian manuscripts and detached folios [individual leaves of a manuscript] came on the market. Berenson felt that this was an opportunity to collect these types of works, and as a result he was able to gather some important examples.”

The exhibition is the first chance to view many of these works outside of Villa I Tatti, Berenson’s home in Florence that he bequeathed to Harvard. (The villa now serves as the Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.) A New Light is also a window into 14th- to 17th-century Persian painting from Iran and Central Asia.

Unlike European paintings from the same period, Islamic and Persian paintings usually appeared only in manuscripts. “They weren’t necessarily religious or made for any religious context; they were meant to be read and owned as prestige objects by high-level patrons such as rulers, princes, and court officials,” Yoltar-Yıldırım said. In addition to manuscripts, artists prepared individual paintings for placement in albums. Often, these works were accompanied by calligraphy.

When early 20th-century art dealers sought to trade Persian paintings like these, they often cut them directly out of manuscripts—losing important textual (and contextual) information in the bid to make individual sales. Berenson’s collection, assembled during this same time, is something of a rarity: it contains three nearly-intact manuscripts and detached folios that are mostly from known manuscripts.

Straight from the Villa

Yoltar-Yıldırım’s visits to Villa I Tatti were essential in organizing A New Light on Bernard Berenson. With a fellowship from the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, as well as the support of the museums and I Tatti, she spent the summer of 2015 at I Tatti’s archive and library, researching Berenson’s collection.

“Through reading Berenson’s correspondence with art dealers and other colleagues, I could tell he was drawn to certain objects to acquire,” Yoltar-Yıldırım said. “The letters helped me connect the objects and his purchasing history.”

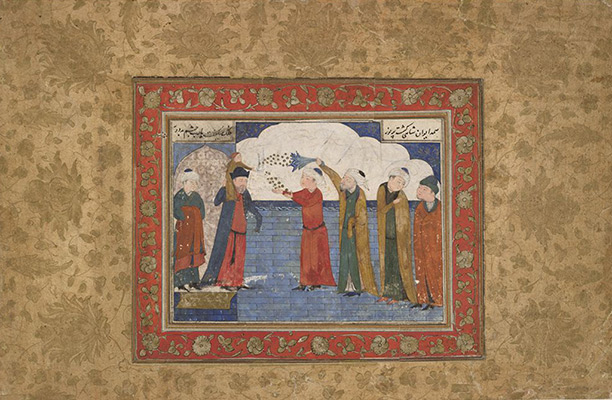

In addition, Yoltar-Yıldırım learned more about contemporaries of Berenson’s who also collected Persian paintings from the same period, bringing to the fore collectors who today are lesser known. One such collector is Sarah Choate Sears, a wealthy Boston artist who gave the Fogg Museum her sizable collection of Islamic art, including the 15th-century folio Child Showered with Money. The painting, which was likely cut from an unfinished or damaged manuscript and remounted as an album page, is featured in the exhibition. (It’s also what Berenson was viewing in the photograph Sears took of him as he looked at her painting, also included in the exhibition.)

A Rare Viewing Opportunity

Although the I Tatti works are in relatively good condition, Berenson’s 15th-century Timurid manuscript, generally known as the Baysunghur Anthology, came to Harvard especially in need of repair. Torn and loose sewing made the folios rub against each other—not ideal for their long-term preservation. To solve this problem, Katherine Beaty, a book conservator from the Weissman Preservation Center of Harvard Library, temporarily removed the binding. She plans to sew the folios back together in a way that prevents further damage.

In the meantime, however, several of the separated folios will be displayed simultaneously in the exhibition—a rare opportunity to see multiple pages from a single manuscript at once.

“The manuscript displays the highest standards in calligraphy, illumination [floral decorations], and illustration achieved in Baysunghur’s court workshop,” Yoltar-Yıldırım said. “Visitors can absorb the beauty of this anthology and learn more about its text and history from the wall labels.”

All of the I Tatti objects in the exhibition stood to benefit from technical study. Bringing them to the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies allowed conservation scientist Katherine Eremin and paper conservator Penley Knipe to analyze the materials and pigments used in the objects. Through careful study, Eremin and Knipe were able to learn more about when, where, and how the paintings were made. Their findings will be incorporated into essays in a forthcoming book Yoltar-Yıldırım is editing for I Tatti.

Other Persian paintings from Berenson’s collection, as well as additional related works collected by Berenson’s friends that are now in the collections of the Harvard Art Museums, the Morgan Library and Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, round out the exhibition. By focusing not only on the art but also on Berenson and his collection, the show highlights the wide appeal of Persian painting across time and geography—and promises to spark even more passion and curiosity.

Keep an eye out on our calendar for gallery talks related to the exhibition.