This is the first story in a series of articles about “museum-speak,” or the lingo of those who work in museums, as well as museum-related knowledge. It is intended to deepen your understanding of the behind-the-scenes workings of a museum, and in particular the operations of the Harvard Art Museums.

When curators and other museum staff discuss the logistics behind setting up and maintaining galleries, they often use terms and phrases that connote activity: “acquisition,” “installation,” “exhibition.” “Rotation” is another of those words.

Nothing’s actually going around in circles, however. A rotation, in museum lingo, is the changing of a work or multiple works on display; as one is taken off view, another replaces it. And there certainly is plenty of behind-the-scenes action involved with each rotation.

In many museums, the practice of rotating objects ensures that light-sensitive or extremely fragile works—often works on paper, such as drawings, prints, and photographs—are not on view for too long. Sometimes, because of the need for specially reduced lighting levels, works slated for rotation are housed in a separate room or on their own wall. In the new galleries of the Harvard Art Museums, works on paper are incorporated among more stable, less-sensitive works.

“It’s a signature of this new installation to have works on paper throughout the galleries,” said Miriam Stewart, curator of the collection in the Division of European and American Art. “Works on paper have their own voice, and we want them to be seen as equals to paintings and sculpture, which traditionally have taken on more prominence in gallery installations.”

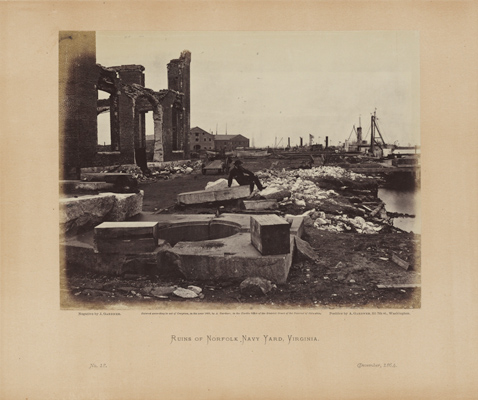

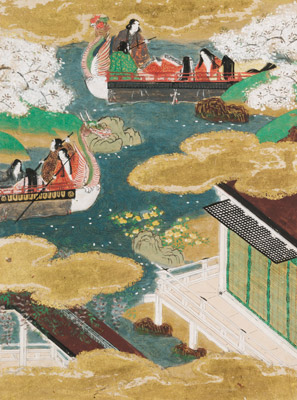

Now, for instance, an album of Civil War photographs is displayed in a glass case, just feet away from 19th-century American paintings by Winslow Homer and Edward Lamson Henry about the impact of that war. A Japanese illustrated Tale of Genji book created in the Muromachi period (1392–1568) is exhibited near painted Asian vases and vessels of the same era.

Because many works on paper must be on view for a limited time, rotations occur every four to six months, depending on the art’s fragility. That means a greater number of works from the museums’ collections may be exhibited over time—a boon to the museums’ teaching and learning mission. It also means more work for the curatorial team, who must plan out rotations far in advance so that the objects can be prepared for display and wall text can be written.

In fact, more than a year before the new museums opened, curators were busy determining how best to incorporate rotating works into more permanent gallery installations. They needed to be sure they would have enough works on paper that would be relevant to and spark conversations with the surrounding works, while also being roughly the same size and shape (in order to fit in allotted spaces on walls or in cases). “It’s tricky, but we’re devoted to it,” Stewart said.

Stewart and her colleagues in the Divisions of Asian and Mediterranean Art and Modern and Contemporary Art have each arranged long lists of works slotted for future rotations (some stretch out beyond the next five years). And though works on paper will be the primary objects featured in rotations, the coming months and years will see other types of objects go on view, such as plaquettes (small plaques made of carved metal or stone), miniatures, and medals.

For now, however, curators—and collections management staff, who install and de-install every object—are gearing up for the first major set of rotations later this month as well as in March. More than 140 works will be rotated (with about 70 rotating out and 70 rotating in, including a few books and albums whose pages will be turned). An additional handful of works will rotate as part of the current special exhibition Mark Rothko’s Harvard Murals. Stay tuned for more stories revealing highlights from our upcoming rotations.