This story is part of a series of articles about “museum speak,” or the lingo of those who work in museums, as well as museum-related knowledge. It is intended to deepen your understanding of the behind-the-scenes workings of a museum, and in particular the operations of the Harvard Art Museums.

The Harvard Art Museums have a state-of-the-art climate control system—and it’s energy efficient to boot. By consistently keeping the air temperature between 70 and 73 degrees and the relative humidity between 45 and 55 percent, the facility provides optimal conditions for thousands of works of art that are on permanent and temporary display. (It’s also a comfortable climate for visitors.)

But for certain three-dimensional objects in the collection, that climate is not quite ideal. Those objects, often made of metal that can actively corrode in a humid environment or made of uncommon or organic materials, require display and storage conditions tailored to their individual needs. That’s where “microclimates” come in. In a museum setting, a microclimate is created inside an airtight enclosure such as a Plexiglas case. Essentially, it’s a carefully controlled environment within another environment.

In a historical building such as the Harvard Art Museums facility, a microclimate presents “an economical way to take care of objects” that require specific climate conditions, said Angela Chang, assistant director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies and conservator of objects and sculpture.

It’s also “an important way to ensure that our works of art can be protected and enjoyed by visitors for many years to come,” said Karen Gausch, manager of exhibition production and collections care. “As we have gained greater control over our interior conditions, we are using microclimates less frequently, but they remain an essential aspect of certain galleries and are critical to the display of some objects.”

Special Cases

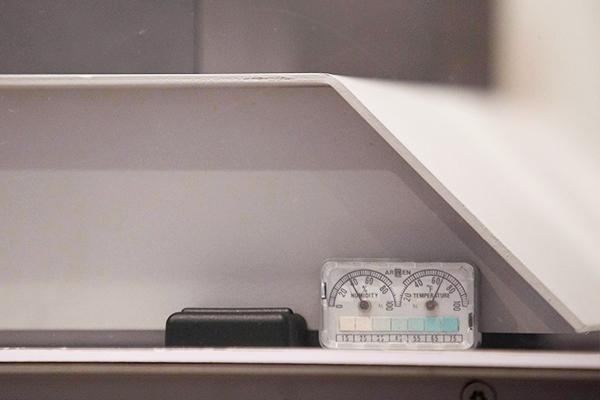

Like frames, microclimates and the display cases they are in aren’t intended to attract attention. In fact, none but the most discerning viewer would probably realize the difference between a regular display case and one with a microclimate. The only hints are two small logging devices the size of matchboxes (kept below the objects, within the cases), which help collections management staff and conservators monitor the conditions inside by providing temperature and relative humidity readings. In addition, small fans hidden in the bottom of the pedestals support the microclimates by circulating air at regular intervals.

Just a handful of microclimates are currently in use. Two surround leaded bronze sculptures in the ancient Mediterranean and Near Eastern art gallery (3740), including Horus Falcon Wearing Crown of Upper and Lower Egypt with Uraeus (mid-7th–late 6th century BCE). A third is around a sculpture representing the Jain figure Suparsvanatha (7th–8th century), made of cast bronze, in the South Asian art gallery (2590). The relative humidity in these cases is kept much lower than the rooms they are in to prevent active bronze corrosion.

The Silver Cabinet, on Level 2, also maintains a microclimate. The cabinet displays American and European silver objects made from 1600 to 1850, such as John Coney’s “Stoughton Cup.” To prevent the silver from tarnishing, these cases are equipped with hidden compartments containing a “scavenger,” a filtering material that removes tarnish-causing sulfur from the air inside the case.