The stone steps were deeply worn from 400 years of papermakers treading on them. That was one of the first things I noticed when I arrived at Moulin du Verger, a paper mill in Puymoyen, in southwest France, for a weeklong workshop on blue paper and its use by artists through time.

Making Blue Paper in the French Countryside

As a paper conservator at the Harvard Art Museums, I have years of experience working with paper in the Straus Center. I have also taught class sections at Harvard about paper and papermaking, helping undergraduates make paper in our lab’s big metal sink. But being at Moulin du Verger was different. It gave me the chance to learn from the pros in a historic setting. I was thrilled, to say the least.

The six other workshop participants and I started our week by touring the mill. We visited the rag room, where countless piles of old sheets and linens were stored, awaiting their turn to be cut up. We saw, in action, the very loud stampers that broke down these rags into fiber bundles and the Hollander beater that further converted the bundles into individual fibers ready to be made into paper.

That first afternoon, we began to make paper using fibers made from rags mixed with new cotton fibers. Jacques Bréjoux, master papermaker and owner of the mill, led us in this endeavor. I was surprised how hard it was to pull the paper mould smoothly from the vat of water and pulp. The process by which the fibers and water slurry were lifted up on a paper mould and coalesced into a piece of paper was absolutely magical. (For a basic introduction into making paper, this video by Chancery Papermaking is excellent.)

The workshop included lectures about natural dyes, the history of dyeing and the dye trade, the history of blue paper, and papermaking around the world. We learned about making natural dyes from master dyer Philippe Chazelle and took turns coloring wool with indigo, cochineal, madder, and other natural dyes, to learn more about the working properties of each colorant.

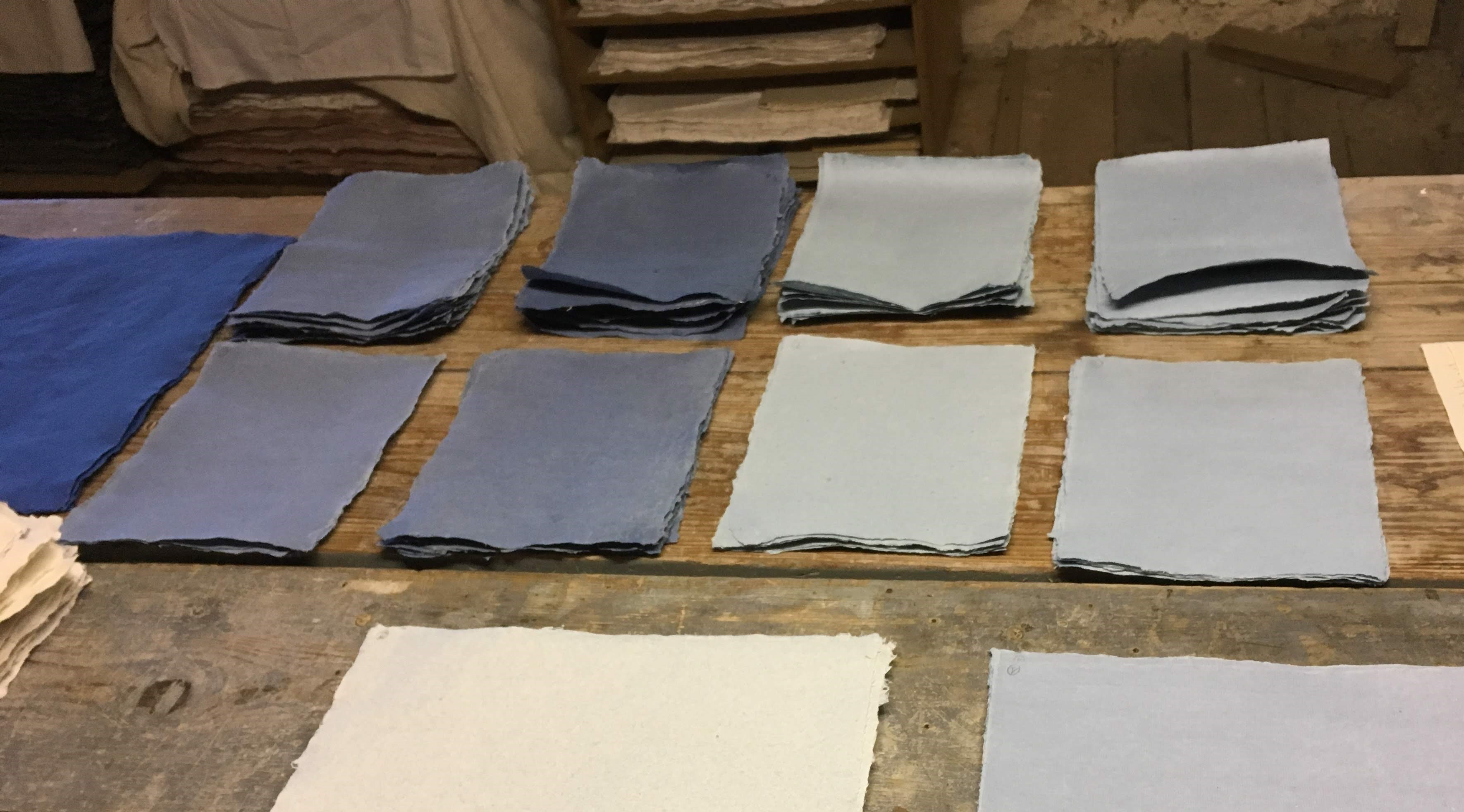

We made blue paper using the traditional blue dye, indigo, which comes from Indigofera tinctoria, a plant native to India and other tropical locales. Indigo and woad, a plant from which a chemically identical dye to indigo can be extracted, were traditionally used to color papers blue. Woad grew in the Toulouse area of France and was used until the importing of indigo from India became common. Indigo was preferred over woad because it had more coloring strength and grew more readily. Historically, blue-dyed fibers either came from blue textiles or by adding a colorant, usually indigo, to the paper pulp. Prussian blue, a synthetically produced pigment of ferric ferrocyanide, was developed in 1704 and was first used to color paper around 1770. Prussian blue was preferred because it tinted paper much more efficiently and did not need to be imported from the tropics.

One of my favorite parts of the workshop was hanging the newly made papers in the drying loft after most of the water had been squeezed from the paper stack in a press. Although I had read about and seen pictures of drying lofts, this was the first time I had been able to visit one. The loft is situated in the mill’s attic, where side louvers can be opened to allow for controlled airflow and humidity. Later, we also “sized” our papers by dipping them in a solution of thinned liquid gelatin so that any drawing or writing ink applied to the paper wouldn’t bleed. Because the papers were damp after being sized, they were hung again in the drying loft.

Another wonderful part of the course was looking closely at old papers with Jacques and Leila Sauvage, the paper conservator who conceived of the workshop. In one forensic-based session, Jacques and Leila each shared examples of sheets that showed characteristics and anomalies of various papers. A group of people stared at the structure of paper made hundreds of years ago and hypothesized what happened to it during manufacture. This kind of close looking is exactly what we do at the Straus Center. My experience at Moulin du Verger will be put to good use when teaching with and examining papers in our collections.

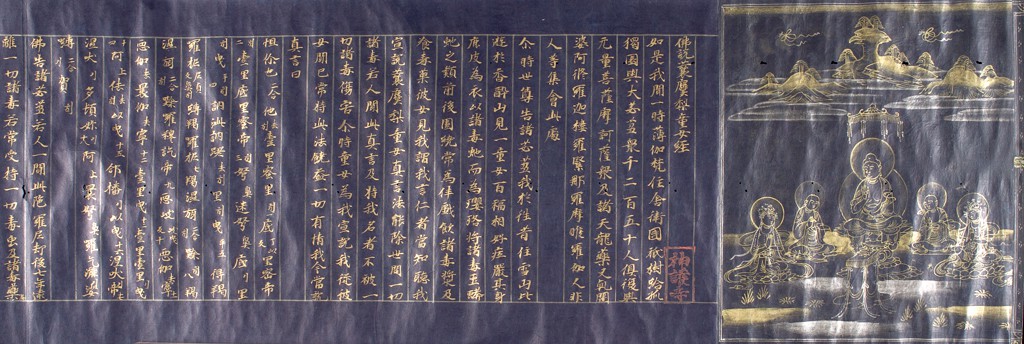

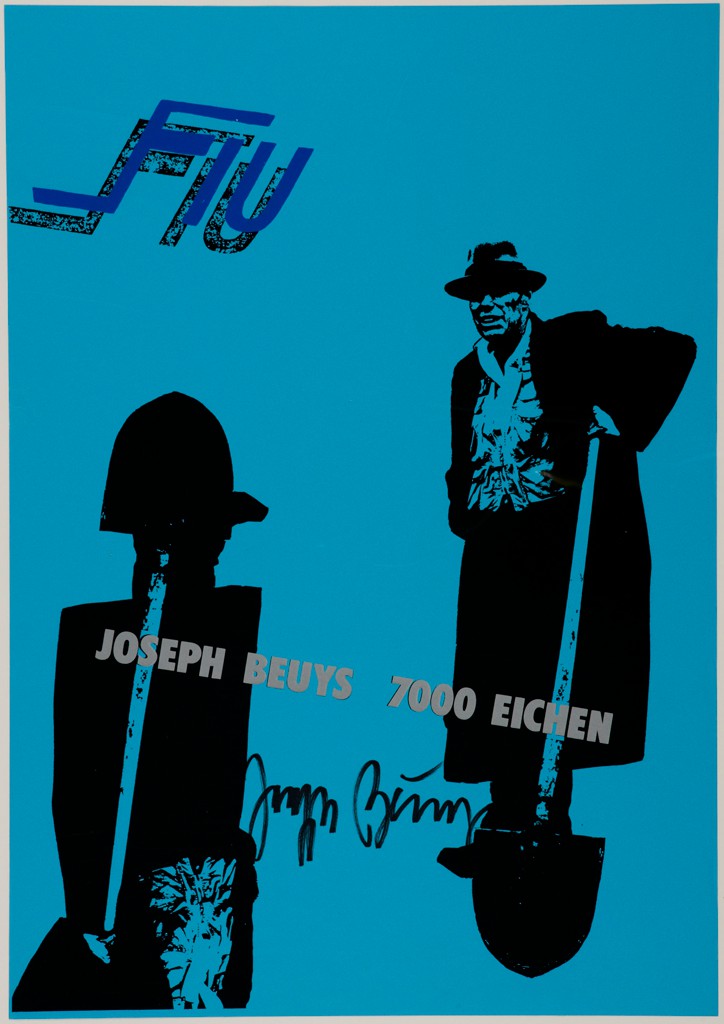

The Harvard Art Museums collections include a large number of drawings executed on blue paper. Blue paper makes an excellent mid-tone for working in black chalk and adding highlights in white chalk, as seen in this figure study by Jan Asselijn and in the charmingly drawn dromedary by Jean-Baptiste Oudry, seen at the start of this article. Thomas Gainsborough made excellent use of black and white chalks in a landscape, where some of the black chalk (in the foreground) is blended using a cloth stump. The Harvard Art Museums own prints on blue paper as well, such as a wonderful woodcut by Hendrick Goltzius. There are also some stunning Japanese works on blue paper, including a Jingo-ji sutra that is painted and written in gold and silver on indigo-dyed paper from the Late Heian period (898–1185). More recently, Joseph Beuys used blue paper for his screenprint Joseph Beuys, 7000 Oaks.

There are not many papermaking mills like Moulin du Verger left in Europe. This made the experience of being there even more special. This mill may close someday, so the opportunity to make paper by hand and to learn from people who make paper all day was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. I hope you enjoyed this armchair travel to southwest France, and I encourage you to explore our collections of works on blue paper.

Penley Knipe is Head of the Paper Lab in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies at the Harvard Art Museums.