When this 5th-century BCE Greek red-figure wine jug entered the objects lab of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, it was in less than ideal condition. The wine jug had at one point been broken and was reassembled, but the restored neck, trefoil spout, and handle were not the right size or shape; there were new, unstable cracks along the old joins; and, in the words of Conservator of Objects and Sculpture Tony Sigel, it rattled when tapped.

The conservation of this jug, or oinochoe, however, is only the latest development in its story. 1960.354 has had a very long life, which began on a potter’s wheel in Athens some 2,500 years ago.

First, what do we know about it? Its shape is unusual, with the upper body of a wine pitcher and a foot more typical of an oil flask. The decoration features a woman playing a barbitos, a type of lyre associated with leisure and revelry. She might be the famous Greek poet Sappho of Lesbos or an anonymous entertainer at a drinking party. There are two inscriptions on the vase—one reads “ka[l]e,” in the field to the right, meaning “she is beautiful” (maybe our musician?) and the other, “kalos,” meaning “he is beautiful,” appears to the right of her head, almost as if the word is coming out of her mouth. Perhaps she is praising the beauty of a boy or man as she sings.

A Long Journey

As it seems the wine jug was meant for actual use rather than mere decoration, one might imagine that soon after the potter sold the vessel revelers poured wine out of its spout at a symposium, the ancient Greek drinking party, while listening to poetry sung to the accompaniment of a lyre. It was then possibly deposited in a tomb, only to be rediscovered millennia later . . .

Of its modern history, we know that sometime before 1903 Henry Hucks Gibbs, Lord Aldenham of England, acquired the oinochoe, because he lent it that year to an exhibition of Greek art at London’s Burlington Fine Arts Club.

One of the richest men of England at the time, Lord Aldenham was a politician and a banker, at one point serving as the governor of the Bank of England and another as its director. Our vessel was likely displayed in his lovely home. He was a member of the Burlington Fine Arts Club, which had the prestigious address of 17 Savile Row, and was one of the many private owners of Greek art who shared their collections during this celebrated exhibition. The show was extremely well attended, according to Harold Fowler, writing for The Nation in 1903:

A remarkable exhibition of works of Greek art, gathered almost entirely from private collections in England, is now open at the Burlington Fine Arts Club . . . Almost every object exhibited is an exceptionally fine specimen of its kind, so that a selection of those that can be mentioned in a short letter must be made more or less at haphazard . . . The room of the Burlington Fine Arts Club is crowded by midday. It is to be hoped that this success will lead to further efforts. There are many works of Greek art hidden away in private houses, where they serve no useful purpose except as they may give their possessors an occasional moment of pleasure. If these could be occasionally exhibited in London, the gain would be—from this year’s exhibition it already has been—great. (Fowler 1903)

With such a breathless review, one wonders how our vessel appeared to visitors of the exhibition. Was it already broken apart and reassembled? Here is what that exhibition’s catalogue wrote about it:

With red design on black ground. A girl wearing a chiton [a long tunic] with diploïs [overfold], and a drapery thrown over the arms, moves to the right playing a lyre. Her hair is dressed in formal rows of curls in front and on the back of her head she wears a cap or folded handkerchief. Good, vigorous drawing. The oinochoe is put together out of several fragments. Lent by the Lord Aldenham (Burlington Fine Arts Club 1903)

It doesn’t seem that its reassembly was an offense, but in a 1939 Journal of Hellenic Studies article, the revered classical scholar and connoisseur of Greek vases John Beazley describes it as having “a mouth and neck hardly original,” and he goes on to say that these restorations “had disappeared when I saw it, in bits, some years ago; [it] was sold at Sotheby’s the year before last; and has since been cleaned and restored” (Beazley 1939).

It is clear then, that over the years work had been done on our oinochoe, but to what extent and when is less certain. Beazley notes that it was sold in 1937 at Sotheby’s, but to whom we do not know. It might have been sold to the classical archaeologist David Moore Robinson, who bequeathed it, among many other objects from his extensive collection, to the Harvard Art Museums upon his death in 1959. Robinson is most known for the discovery and excavation of the ancient city of Olynthos, in Greece.

Our oinochoe has been exhibited twice at the Harvard Art Museums since we first received it in our collections: in The David Moore Robinson Bequest of Classical Art and Antiquities: A Special Exhibition (May 1–September 20, 1961) and The Ideal of the Everyday in Greek Art (January 31–May 31, 2012), in our teaching galleries. (Read Harvard alumna Isabel Hebert’s experience of viewing works in that installation here.)

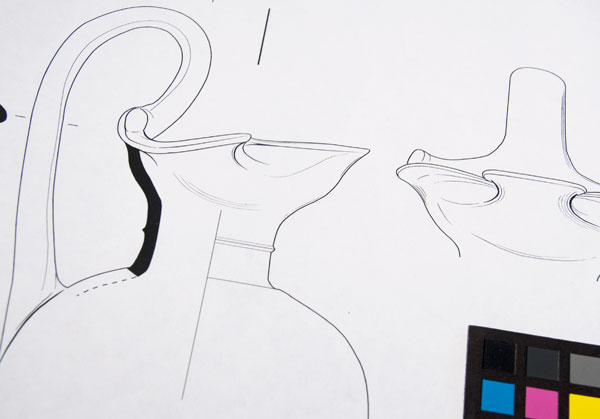

Now it is time to prepare our oinochoe for exhibition in the new galleries in the Harvard Art Museums, opening in fall 2014. And so we return to Tony Sigel’s difficult conservation project, which required him to disassemble, clean, and reassemble the oinochoe body. One of the main challenges was to remove the modern (and incorrectly sized and shaped) neck, trefoil spout, and handle and to create a new one. But because the vessel had an unusual shape, he needed help finding a comparable vessel to recreate the parts properly. Susanne Ebbinghaus, the museums’ George M. A. Hanfmann Curator of Ancient Art, identified a similar vessel in the collection of the British Museum. Her colleague there kindly had the vessel drawn and provided detailed photographs, which were going to be key to Tony’s treatment.

From Potter’s Wheel to Turntable

With the British Museum’s images as his guide, Tony planned his strategy to make a new neck, trefoil spout, and handle. To achieve an accurate, sympathetic restoration, he would need to use materials and techniques close to those the potter originally used. Instead of clay, for instance, he opted for plasticine, which is essentially clay mixed with paraffin instead of water. The neck and spout would be shaped while spinning, as was the original. And instead of a potter’s wheel, he would use, yes, a turntable. He would next make molds from the plasticine and cast the pieces in plaster of Paris, which he could then attach to the vessel.

On a square of Plexiglas mounted on the spindle of the turntable, he formed the neck and the spout as if on a spinning lathe, slowly removing material from the plasticine mass. He held tools against an adjustable, locking arm.

Once the neck and spout were roughly shaped, Tony hollowed out the interior as he refined the exterior, taking small cuts of the clay to avoid collapse. The final interior and exterior surfaces were carefully smoothed and burnished with tools, leaving a fine, wheel-thrown texture. Finally, with the funnel-like shape complete, he created the trefoil shape. As the ancient potter did, he pinched the two opposite edges of the rim inward with fingers and tools to form the three lobes. Choosing the precise points at which to squeeze was key to making a trefoil shape with the correct proportions—if he hadn’t chosen the right points, he would have to start all over. And, as a potter would with a wheel-thrown clay vessel, he used a wire to cut the neck and spout from the turntable.

Tony then focused on the handle. The original potter would have shaped his clay into the “D” shape cross-section by a pulling technique or extruding the soft clay through a die. Because plasticine is much harder than clay, Tony had to cut and form a strip, rolling it between flat glass sheets and wood strips to recreate the unique shape. Again using the drawings as a guide, Tony bent the strip into the correct curvature and cut it to fit the vase. After attaching it, he added the small points on either side using the photographs as reference.

Next, Tony transformed the plasticine neck, spout, and handle into a permanent, stable material by creating flexible silicon rubber molds and casting the pieces in plaster of Paris. After consolidating the plaster with a stable resin, he attached the recreated pieces to the oinochoe body. The vessel was complete once again.

To finish the treatment, Tony filled in other large and smaller losses on the body, correcting damages inflicted not just by accident, but also by earlier restorers. He inpainted the fills with stable, reversible paints, should future scholarship reveal new information.

Now that our oinochoe’s treatment is at last complete and its original contours and beauty are restored, 1960.354 is ready for its debut in the new galleries of the Harvard Art Museums.

Beazley, John. “Notices of Books,” Journal of Hellenic Studies LIX/1 (1939): 153. Burlington Fine Arts Club, Exhibition of Ancient Greek Art, London: Burlington Fine Arts Club (Chiswick Press), 1987, 107. Fowler, Harold N. “Greek Art at the Burlington Fine Arts Club,” The Nation, July 30, 1903, 91–92.