Doris Salcedo’s chair sculptures are full of contradictions. From afar, they seem familiar and even inviting, giving the impression of simple wooden furniture. Up close, however, they’re deeply unsettling: the chairs are backless; some are fused together in jarring combinations; and all bear subtle and not-so-subtle areas of damage.

“You look at these objects and think, can wood crumple?” said Mary Schneider Enriquez, the Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, standing in a room filled with the disconcerting structures that are part of the special exhibition Doris Salcedo: The Materiality of Mourning (November 4, 2016–April 9, 2017). In the dimly lit gallery, the sculptures appear to emit a slight glow; the purposeful lighting accentuates areas that seem mangled or missing. “After looking more closely, you realize that these works aren’t made of wood at all,” Schneider Enriquez said. “They’re stainless steel, carved by hand to appear to have wood grains and nail holes. The longer you look, the more you realize how detailed these pieces are and how seemingly impossible it is that they were created in the way that they were.”

Indeed, making these objects involved a laborious process for the Colombian artist and her studio, from creating wax and paper models for casting individual pieces, to assembling parts, to carefully carving each detail by hand. This complexity is typical of Salcedo’s work, which challenges the limits of materiality and pushes contemporary sculpture in new directions. Besides the chair sculptures, The Materiality of Mourning features a hand-sewn tapestry of rose petals, cement-filled fused furniture, and blouses made of needles and silk—all of which attest to Salcedo’s exhaustive focus. “There’s nothing about Salcedo’s work that isn’t painstakingly controlled down to every single detail,” Schneider Enriquez said.

The Handmade

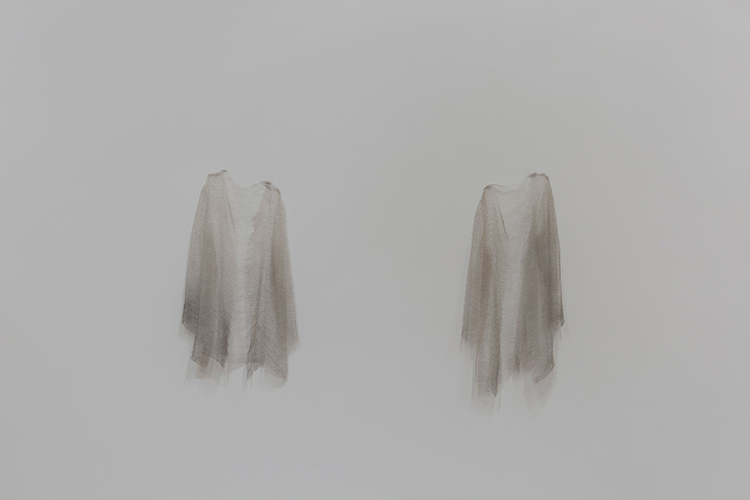

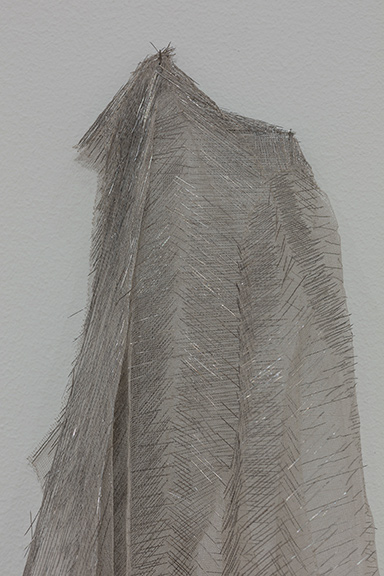

Salcedo’s use of unlikely materials is perhaps nowhere more apparent than in her four blouse-like sculptures, titled Disremembered II (2014) and Disremembered VI (2015–16). She created the works in response to her experiences meeting mothers who had lost their children to gun violence in Chicago. A reflection of the constant presence of grief for mourners, the textiles both imply and inflict pain: each piece contains more than 12,000 tiny burnished needles, handwoven with silk thread. “The blouses appear to be both menacing and beautiful specters,” Schneider Enriquez said.

The creation of the works was necessarily an iterative act, as was Salcedo’s A Flor de Piel, made of thousands of hand-sewn rose petals. This process not only gives the works a personal quality, said Schneider Enriquez, but also references a rich tradition of handmade crafts in Salcedo’s native Latin America.

Though stitching the blouses was a repetitive and isolating process, the completed objects project a collective message. “This work is about forcing us to remember and acknowledge those whose deaths are unrecognized and to realize that each victim is an individual with a mother, father, siblings, and friends who continue to mourn them,” said Schneider Enriquez, who was able to witness Salcedo make one of the pieces when she visited her studio in 2015.

In addition, the works’ countless stitches recall “putting yourself in a process of repeating something to be able to get through the mourning,” Schneider Enriquez said. As with all of Salcedo’s sculptures, the story of their creation is integral to their meaning.

Groundbreaking Materiality

The subtle presence of the Disremembered sculptures—which are hung on the wall as if they were real pieces of clothing—makes them a stark contrast to some of Salcedo’s earlier works, and particularly to the incredibly dense untitled furniture pieces also featured in the exhibition. In a conversation with Salcedo, moderated by Schneider Enriquez, Harvard professor Elaine Scarry referred to the Disremembered pieces as “on the cusp between making and unmaking. They are so delicate and exquisite that it seems as though they are coming midway in the air between mental creation and material realization,” she said.

That suggestion of simultaneous presence and absence underscores how Salcedo has pushed sculpture to its limit. “She challenges materiality in a way that is not only groundbreaking but has also blurred the lines between what is sculpture and what is performance,” Schneider Enriquez said. By making materials perform in unexpected and unlikely ways—forcing stainless steel to appear as painted wood on purposely mangled chairs, creating blouses with thread that is literally painful, and building a tapestry out of rose petals and thread—Salcedo is “pushing the question of ‘what is sculpture’ to its limit,” Schneider Enriquez said.

“Sculpture by Salcedo is something that’s completely handmade and yet monumental,” she said, “and that’s one of the things that is so exciting about her work.”