In some ways, learning how to examine art is much like learning a foreign language. Both entail a process of translation and making sense of something that may not be immediately perceived. “One must dedicate considerable time and effort to achieve mastery of either a new language or an understanding of a piece of art,” said Danielle Carrabino, associate research curator in European art at the Harvard Art Museums. Both pursuits can be frustrating, “but when a language or a work of art clicks in a student’s head, it is a true delight to witness,” Carrabino said.

This type of “aha” moment occurred last semester in a class at Harvard titled Italian through Art (“Dante Illuminated”), taught in the Harvard Art Museums by teaching fellow Matthew Collins, under the guidance of Elvira Di Fabio, senior preceptor and director of language programs in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures. Di Fabio originally designed the class with a focus on developing language skills; Collins worked with her to shape the current course around Dante Alighieri’s celebrated poem known as the Divina Commedia and its illustrations.

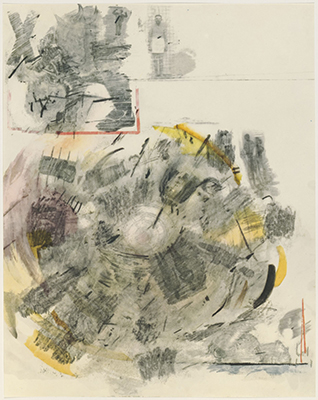

Throughout the fall semester, Collins gave his students frequent opportunities to study original works of art from the museums’ collections. The class viewed a wide range of Dante-related material, from a woodcut illustration in a 15th-century edition of the Commedia to drawings by 20th-century American artist Robert Rauschenberg that relate to the poem’s first canticle (section), Inferno. Incorporating original works into the curriculum gave students the chance to broaden their language skills while simultaneously learning how to encounter art.

In-Person Interactions

During one class session, Collins brought his students to the museums’ Art Study Center, a space for experiencing original works of art from the museums’ collections. A Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, Collins is writing his dissertation on the representational relations between words and images as discussed within Dante’s Commedia and as evidenced in 14th- to 16th-century illustrations of the work. Collins drew upon his expertise to ensure that the Art Study Center visit was filled with highlights of the museums’ Dante-related objects—and as a result, the room was literally packed with art.

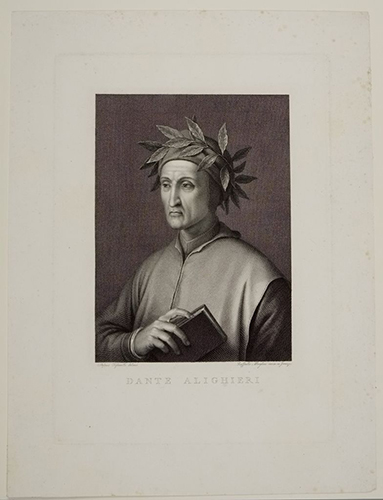

A selection of Rauschenberg’s collage-like Inferno drawings from 1964 filled one table. Hanging on walls and propped on shelf displays were older works: 19th-century engravings and watercolors by William Blake; a densely illustrated etching of Inferno According to Dante by Jacques Callot, dated to about 1612; an 18th/19th-century engraved portrait of Dante by Raphael Morghen; and the woodcut illustration described above. Two paintings by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, the unfinished Giotto Painting Dante’s Portrait (c. 1859) and Beata Beatrix (1871), were also on view, for purposes of discussing how Romantic artists interpreted Dante’s works.

The students took turns describing, in Italian, the individual works of art that had been assigned to them. Besides talking about visual elements, the students explained how the works depicted or related to a specific canto from the poem. The discussion prompted spontaneous critical conversation and additional interpretations among the group, which was exactly the point of the exercise, Collins said.

“The students are learning different manners of visual narration that can be applied beyond Dante,” Collins said. “They’re also applying vocabulary they’ve learned from the text, which requires an active use of the language. It’s a fun and productive form of language practice.”

Interdisciplinary Connections

Besides the Art Study Center, the group often visited the museums’ galleries during class sessions. There they found further connections between objects in the collections and their Italian studies, both linguistic and content-related.

Samantha Perri ’20 said the innovative approach prompted her to learn Italian terms she might not have encountered in a more conventional language class, including those related to narratives of art, such as “monoscenic” (monoscenico) and “poliscenic” (poliscenico). To describe objects accurately, she said, “words I never even thought about before this class became pertinent. At the same time, comparing different works of art and artists required knowledge of how to compare and contrast items clearly in the Italian language.”

It’s not surprising that the interactions with art enriched the language-learning experience, Carrabino said. “There is simply no substitute for viewing a work of art in person, as these objects were often created precisely to be experienced firsthand,” she said.