This fall, visitors to the museums’ Lightbox Gallery—a collaborative space that has previously hosted digital artworks, animations made by Harvard students, and digital tools—have been greeted by the sights and sounds of a much earlier time.

Adding Voices to Harvard’s Past

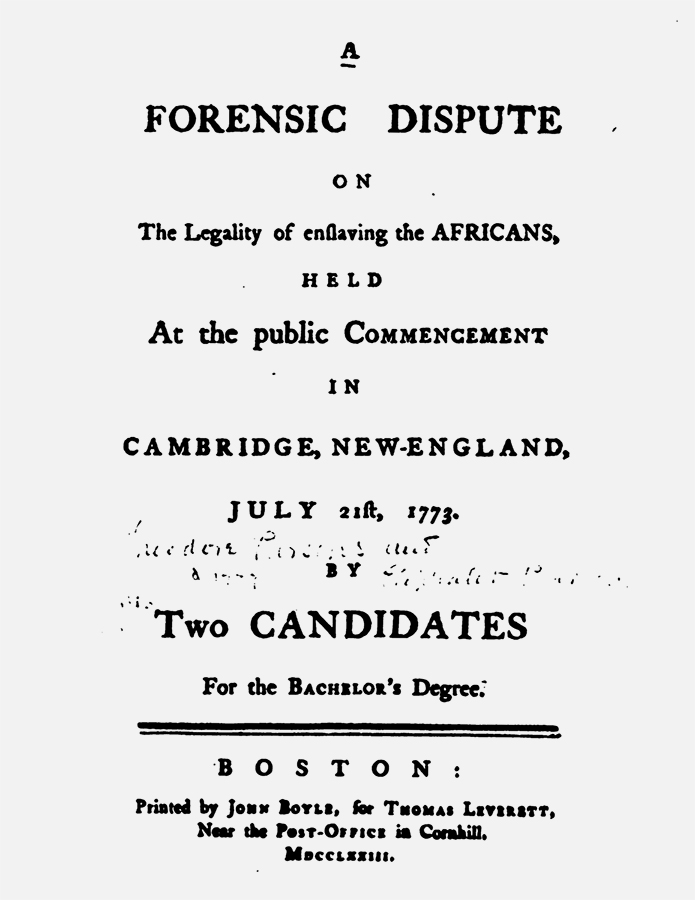

The film on view is No More, America, made by Peter Galison, the Joseph Pellegrino University Professor and faculty director of the Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments, in collaboration with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher, Jr., University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research. It reimagines a forensic disputation—an 18th-century debate form that represented an evolutionary step between the logical, Latin-language syllogisms favored in the 16th century and today’s intercollegiate debates—that was held on July 21, 1773, between 21-year-old seniors Theodore Parsons and Eliphalet Pearson. The students debated the morality of the institution of slavery, which was then legal in Massachusetts, as it was in all of the colonies.

Though these debates were common features of Harvard graduations in the second half of the 18th century (with records of more than 400 deposited in the Harvard Archive), this exchange is the only example for which a full verbatim transcript survives, a circumstance that was almost certainly brought about because of its explosive subject matter. Missing from this conversation, of course, is the voice of an actual enslaved person, leaving the two young men to argue based on abstract concepts gleaned from their study of philosophy and religion.

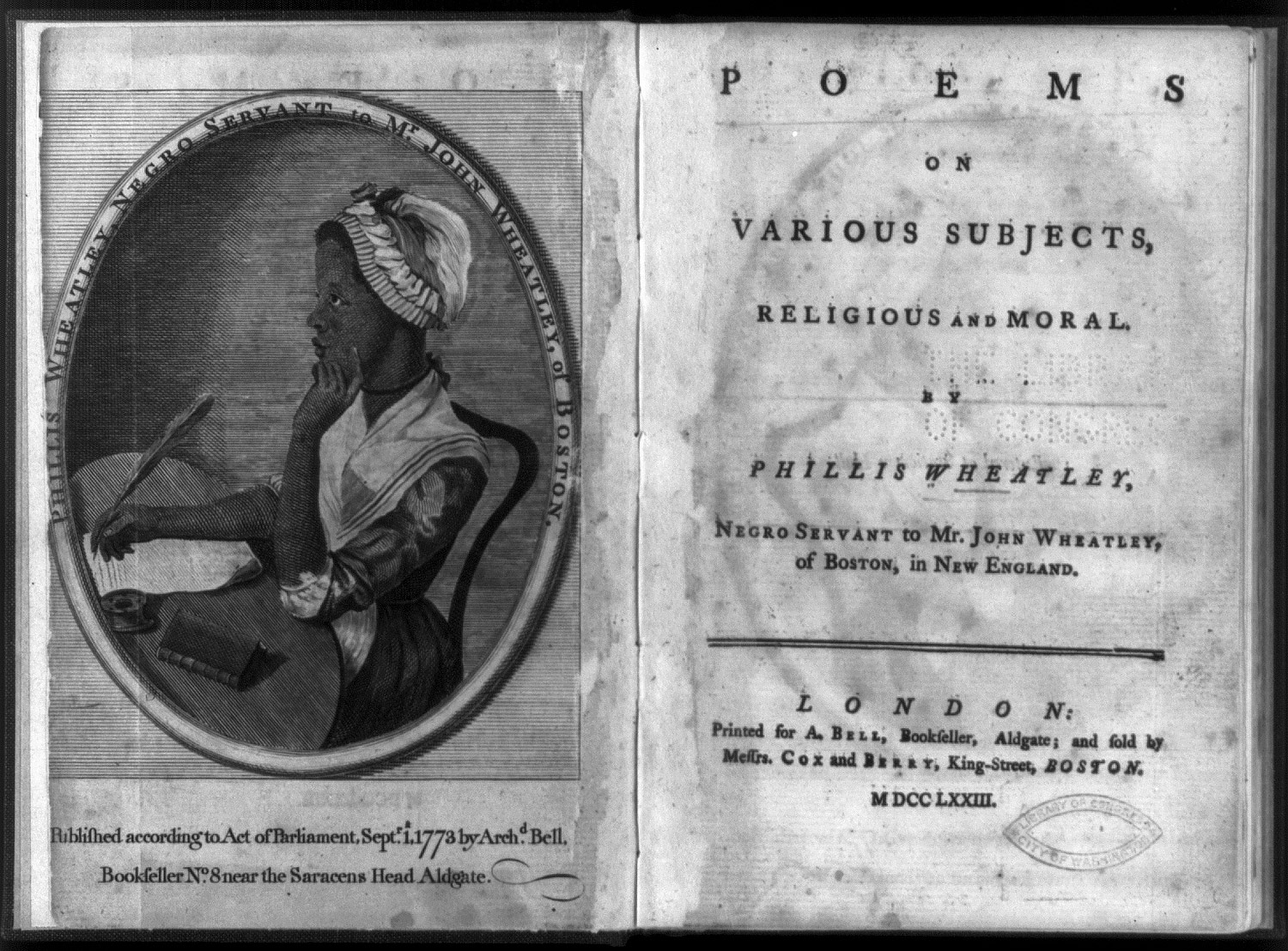

No More, America provides that missing voice, in the form of Phillis Wheatley, also 21, and then an enslaved domestic servant living and working just across the Charles River in Boston. Her book Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral would be published in London later that year. Though her voice would never have been permitted to appear next to those of Parsons and Pearson, today we see it offers a powerful rejoinder to their abstractions, confidently asserting Wheatley’s—indeed, all people’s—basic and immutable humanity.

Engaging on Multiple Levels

The film’s re-creation of a scene from 18th-century Harvard is a perfect match for the museums’ current special exhibition The Philosophy Chamber: Art and Science in Harvard’s Teaching Cabinet, 1766-1820 (on view through December 31, 2017), which invites consideration of hidden aspects of Harvard’s history. “From the beginning [of the development of the exhibition], we were interested as much in celebrating and looking at these objects as in the structures that underpinned them,” said Ethan Lasser, the Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., Curator of American Art and head of the Division of European and American Art. “All the money that supported this city and this university in that period, one way or another, had to do with slavery and its links to the plantation economies of the South and the Caribbean,” Lasser said.

Besides responding to the Philosophy Chamber exhibition, No More, America engages with the Harvard Art Museums’ spaces. The film was produced in the museums’ Naumburg Room, the early 20th-century common room from the New York City apartment of philanthropists Nettie and Aaron Naumburg, which was donated to the Fogg Museum in 1930.

“I think there are many Naumburg Rooms at Harvard,” said Lasser, “and I think that type of space represents this place. It’s a way of making this film speak to the whole institution, because it’s a very celebrated room. This was a way of deliberately troubling that reputation.”

The Naumburg Room also provided the opportunity for what Galison views as one of the film’s most important aspects: dramatic staging. Pearson and Parsons, played by Harvard students Caleb Spiegel Ostrom ’19 and Connor S. Doyle ’19, respectively, stand at lecterns to begin their debate, while Wheatley, played by Harvard student Ashley M. LaLonde ’20, stands on a balcony above them. During the course of the discussion, Wheatley descends the staircase, drawing closer as she responds to the two men—though they fail to notice her, mirroring the historical invisibility of slavery in Boston and at Harvard.

Powerful Intervention

Galison conducted research about the two men in the Harvard Archives and other local repositories. Pearson, who argued in favor of slavery, would later become acting president of Harvard from 1804 to 1806, and also served as the first head of Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. Parsons, who argued against slavery, was presumed killed when the privateer on which he was serving as ship’s surgeon was lost at sea in 1779.

Galison realized the need for a third voice to be added and was struck by the fact that Wheatley, Parsons, and Pearson were all the same age. Even more remarkable, he realized, was that Wheatley was acutely aware of Harvard. Galison chose to open the film with a verse from one of her earliest poems: “To the University of Cambridge, in New England.”

It reminds the two men, “rather beautifully,” Galison said, that “while you’re studying the systems of the world . . . don’t forget to be on your guard against sin; that there’s ethics as well as science in the world. I found that very moving. It’s really from the beginning of her public persona in poetry, and it was addressed to Harvard.”

The film’s powerful intervention is made all the more apparent by its close attention to historical detail, which provided further opportunity for collaboration with a number of Harvard departments. All three characters wear costumes provided by the American Repertory Theater.

The film’s soundtrack is a remarkable piece of 18th-century chamber music written by Joseph de Bologne, the Chevalier de Saint-Georges, a French-Caribbean composer who was the son of a plantation owner and his African slave. De Bologne is now recognized as the first classical music composer of African descent. The piece was recorded for No More, America by members of the Harvard University Department of Music.

In revisiting Harvard’s past, the film reminds us that there is a continued need to confront the legacies and lasting influence of slavery not just in American society at large, but also right here at the university.

No More, America is on view in the Lightbox Gallery until December 31, 2017.

Grant Hamming is the Inga Maren Otto Curatorial Fellow in the Division of Academic and Public Programs at the Harvard Art Museums.