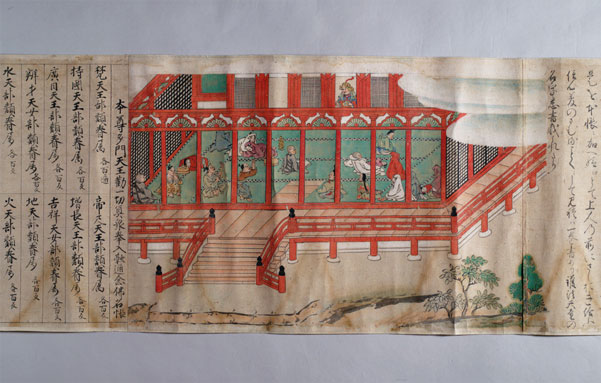

All-night vigils. Paradise and hell. Demons of plague and pestilence. Monks, nuns, emperors, princesses, farmers, and families reciting a sacred Buddhist prayer known as the nembutsu. These are just some of the many dramatic scenes that unfurl from the Harvard Art Museums’ Illustrated History of the Yūzū-nembutsu Sect, Volume I and Volume II, a pair of 15th-century Japanese scrolls attributed to Monk Musashi Hōgen. The scrolls recently received a major conservation treatment and remounting, thanks to a grant from the Sumitomo Foundation in Japan.

“We are exceedingly grateful to the Sumitomo Foundation for its generous support of this important project,” said Melissa Moy, the Alan J. Dworsky Associate Curator of Chinese Art. “The grant allowed us to complete this remarkable restoration and, ultimately, to make these works more stable and attractive for viewing, study, and teaching.”

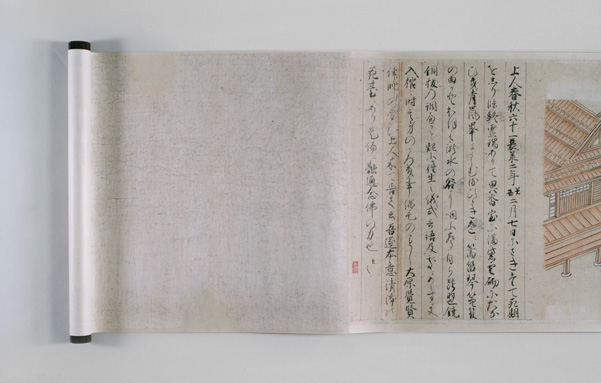

The Yūzū-nembutsu Buddhist sect believed that salvation could be achieved by chanting the name Buddha Amida and that the resulting spiritual merits from this prayer (nembutsu) could be transferred (yūzū) to another person. As this prosperous sect of Pure Land Buddhism spread, its many branch temples used scrolls to illustrate the legend of the sect’s origins and miracles. Rendered in ink, color, and gold on paper, the museums’ newly restored 15th-century scrolls present a version of the sect’s story that, when fully rolled out, is more than 100 feet long.

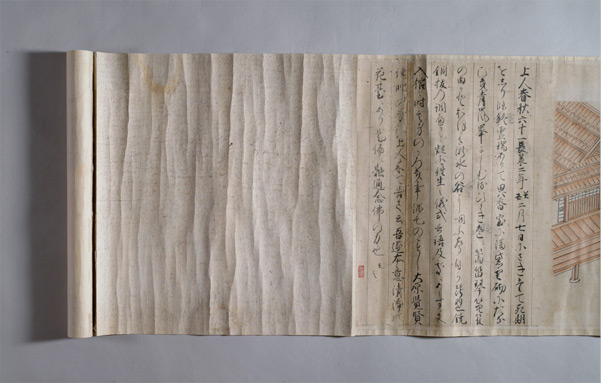

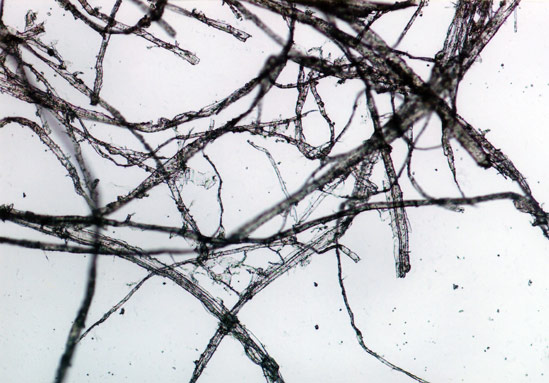

Time had taken its toll on the 500-year-old scrolls. Both had visible paint and paper losses; their linings appeared to be delaminating; and stains, worm holes, and dirt were present. In 2012 the elite restoration studio Handa Kyuseido, in consultation with our Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, began working on a two-year project to treat and remount them. The studio specializes in the restoration of two-dimensional East Asian paintings and calligraphy and is the only conservation studio in Tokyo certified to work on Japanese national treasures.

This complex treatment involved consolidating pigments as well as cleaning and removing surface dirt, staining, and mold. Old paper linings and infill papers were removed and replaced, and creasing was reduced. Losses were infilled and toned to match the painting’s original background color. The scrolls’ knobs, cover silk, and inside cover papers were replaced. During the treatment process, conservators noticed that certain sheets weren’t arranged in the traditional order prescribed by the Yūzū-nembutsu, and after discussions with museums’ staff, the Handa studio conservators rejoined these sections in the correct order.

Upon their return to the Harvard Art Museums, these important pieces of Japanese visual history will provide powerful opportunities for teaching and learning—to students, faculty, scholars, and the public.