When Christian Thompson was admitted to Oxford University in 2010, he had no idea that his mere presence would be groundbreaking.

“I didn’t know that there had never been an Aboriginal person admitted to Oxford; that was a complete surprise,” said Thompson, who earned a doctorate in fine art. Thompson’s first year at the university (along with fellow Aboriginal student Paul Gray, who started at the same time) was filled with “lots of meet-and-greets and press. The historical significance of us being there became a preoccupation for about 12 months,” Thompson said. Even his dining hall hosted a survey show of Thompson’s work, a noteworthy event since it marked the first time that the hall’s historic paintings had been taken off view in 450 years.

After the initial excitement ebbed, Thompson focused intently on his academics and deepened his commitment to the research methodologies behind art making. He was invited to respond to the Pitt Rivers Museum’s photographic collection, which includes an archive of colonial-era images of Indigenous Australians. Classified as “evidence,” these photos were historically associated with the disenfranchisement of Indigenous people; Thompson wanted to encounter them in new ways and pursue a sort of “spiritual repatriation,” an original concept and term coined by Thompson.

“It was really interesting to think about how the photographs could become active participants in and catalysts to forms of new cultural production and contemporary art,” Thompson said. “It was a challenge to think about how, as an artist, I was able to turn something quite dire into something positive and self-affirming.”

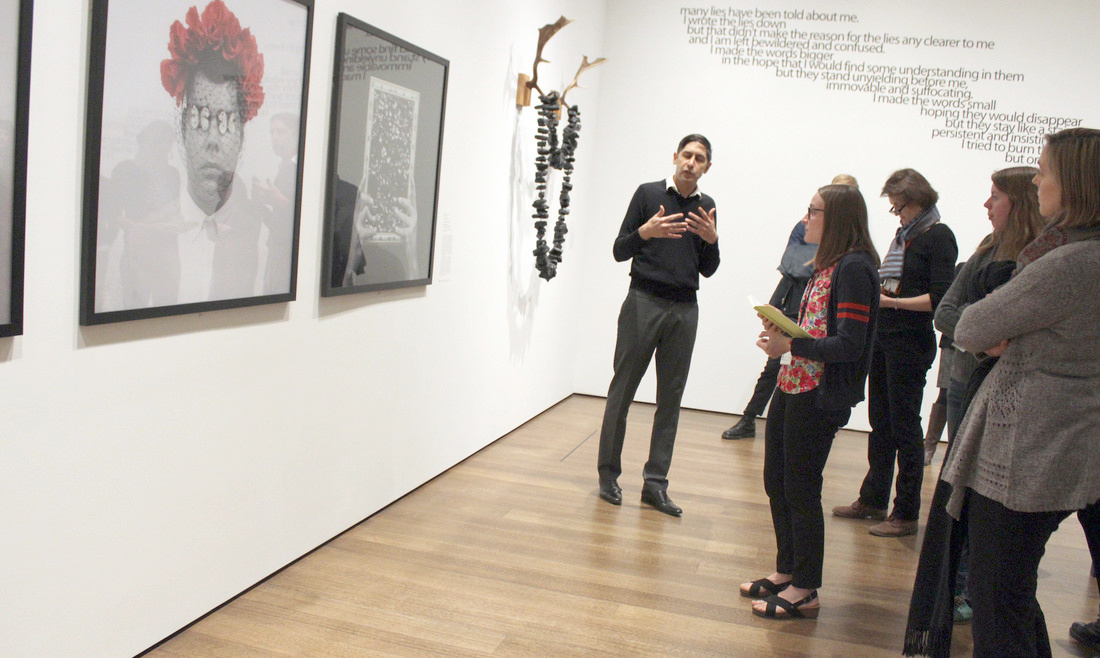

The outcome was a series of photographic images that Thompson titled We Bury Our Own. Thompson himself appears in each, often with his eyes or entire face obscured by iconic objects such as butterflies, flowers, and a tall ship bearing the Union Jack. Images from the series have been exhibited widely, including in Everywhen: The Eternal Present in Indigenous Art from Australia, the current special exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums.