What would a private home in ancient Sardis—capital of the Lydian empire and one-time Roman metropolis—have looked like?

That question has long been on the minds of students, archaeologists, architects, and others excavating at Sardis, in western Turkey. Every summer since 1958, a team from Harvard and Cornell Universities has unearthed and researched this site through the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis.

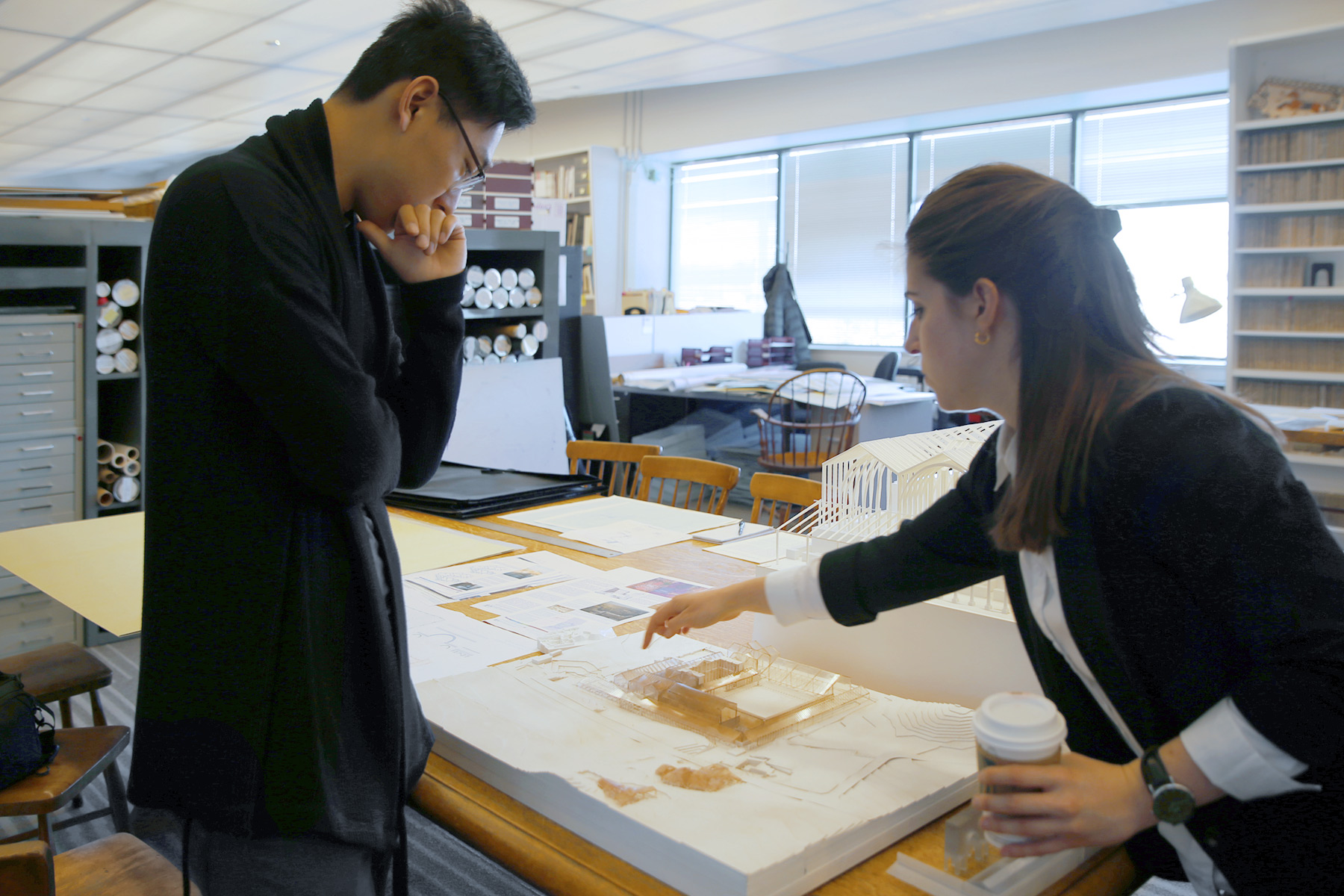

Zhao Sheng, a student in Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, spent the summer of 2018 serving as a student architect with fellow graduate student Kelly-Anna Louloudis. Their role was to survey, document, and help reconstruct (in drawings) the remains of buildings from all periods at the site. “There were several moments during the daily digging when I was struck by the space,” Zhao said. “It’s been there such a long time, and you can feel that history.”

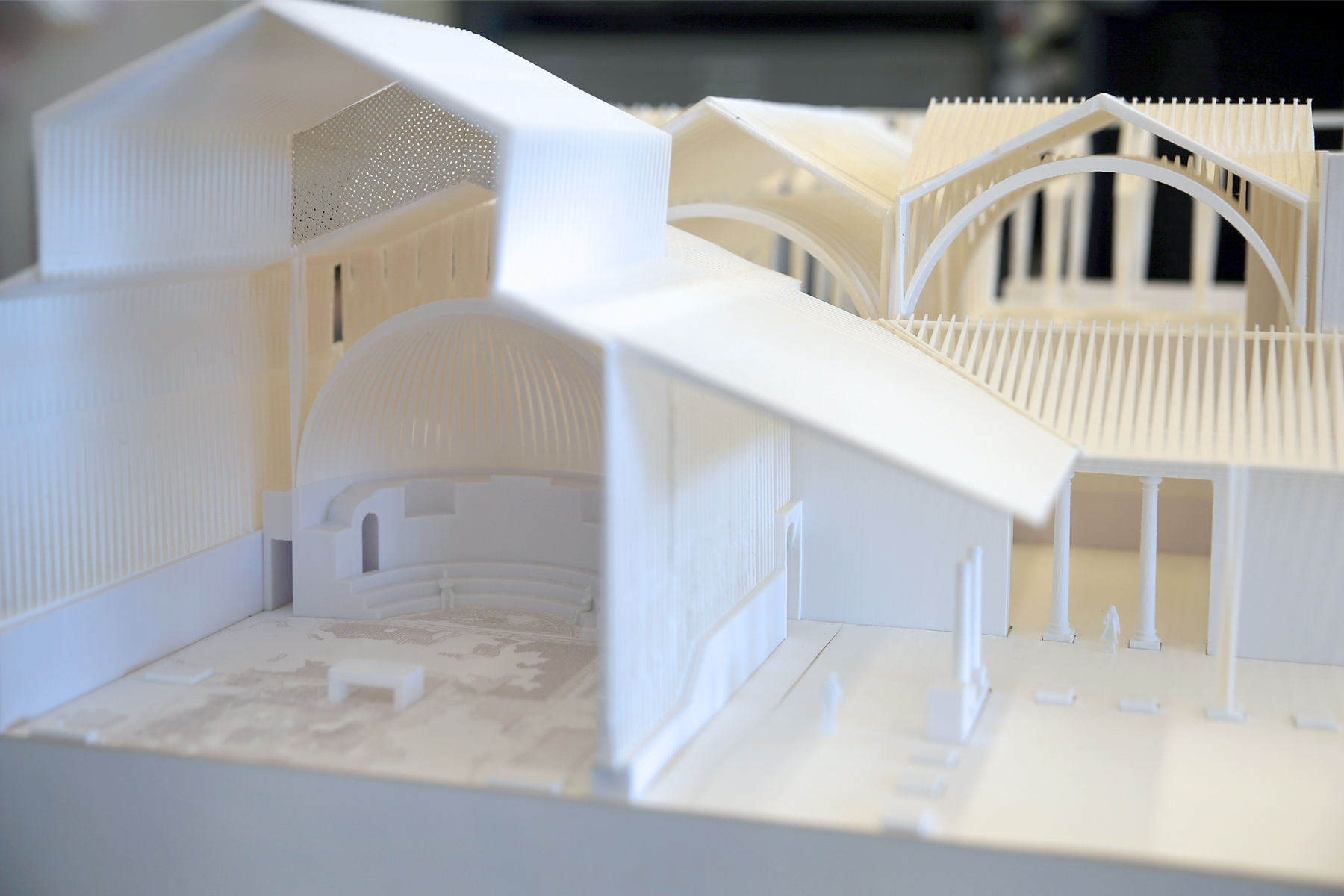

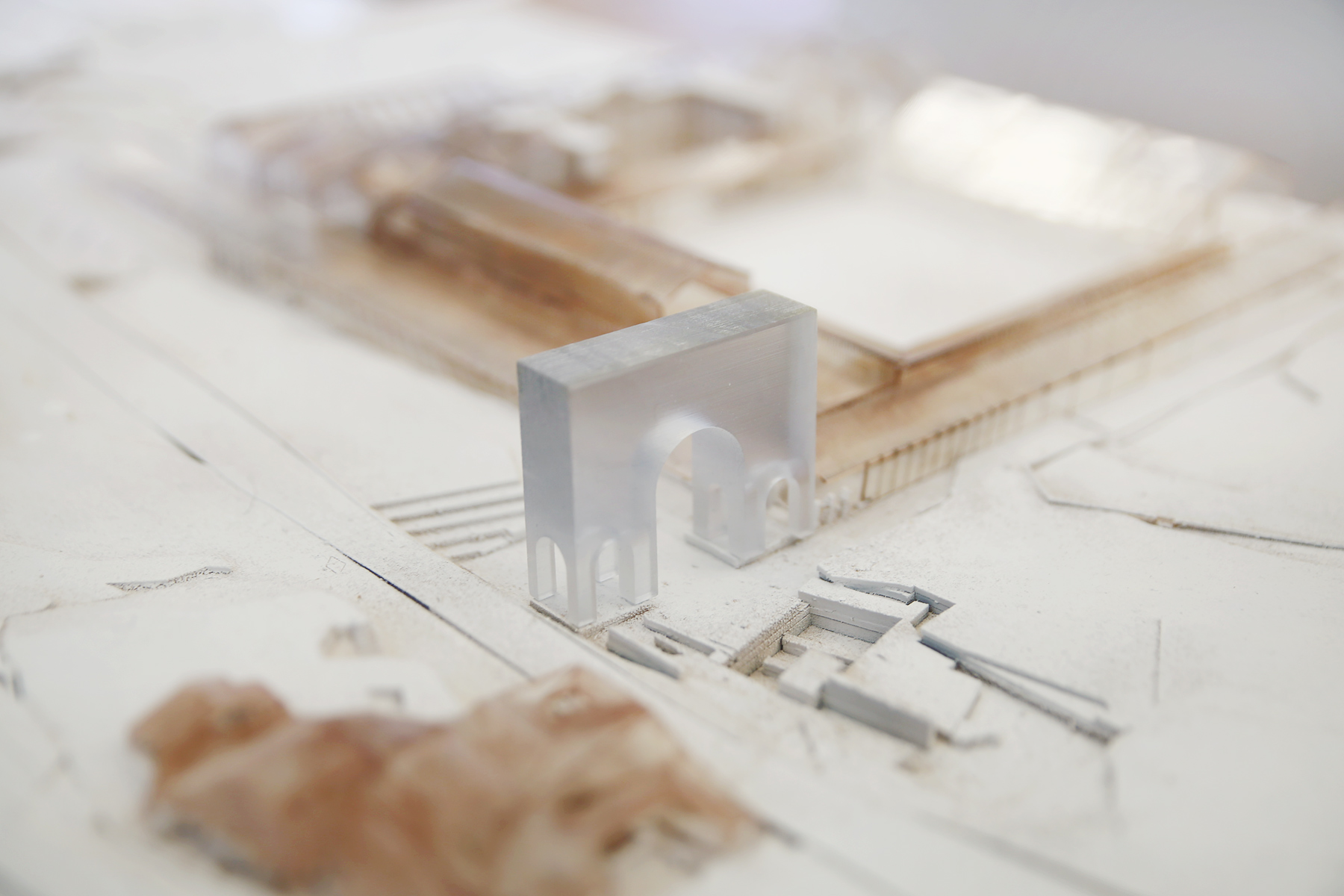

Zhao and Louloudis quickly learned that they shared a keen interest in one particular question: what might Sardis have looked like during various eras? To help get closer to an answer, each designed models of Sardis at different points in its history—and, potentially, its future.

Virtual Views

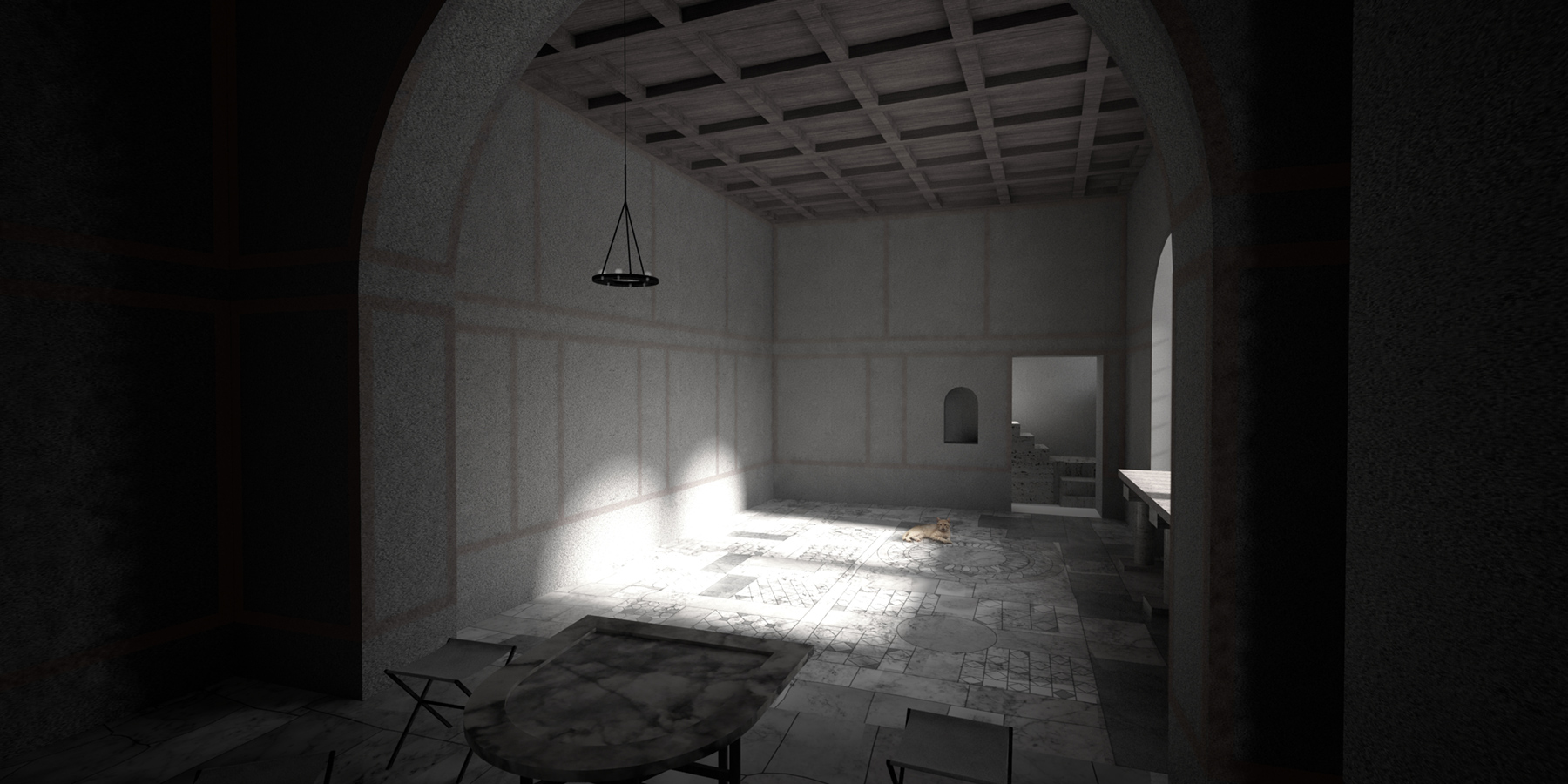

Zhao used digital technology to look back in time. Using software for three-dimensional modeling, image rendering, and image editing, he re-created spaces such as a grand living room of the House of Bronzes (named after the many bronze objects it held). The remains of this Late Roman dwelling’s mosaic floor and furniture informed Zhao’s work.

His renderings are practically photorealistic, complete with dramatic morning light streaming in through the windows. Dogs and cats (based on the real pets of current Sardis staff) are seen sitting or lounging in some spaces, adding a sense of scale and intimacy.