During her first few months of graduate school in 2014, Whitney Barlow Robles, a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard’s American Studies program, visited the Harvard University Archives to gather research for her dissertation about early American natural history. Paging through a folder containing the 1810 lecture notes of Harvard professor and naturalist William Dandridge Peck, Robles made an intriguing discovery: six ink drawings of skulls.

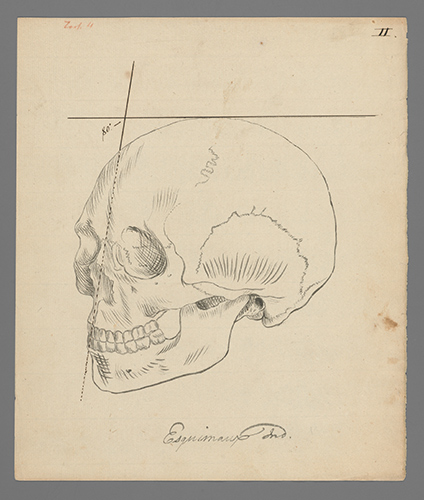

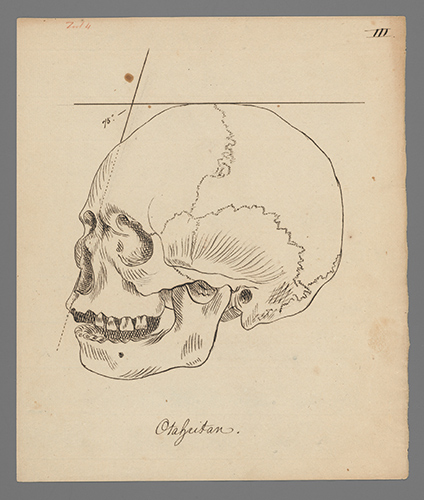

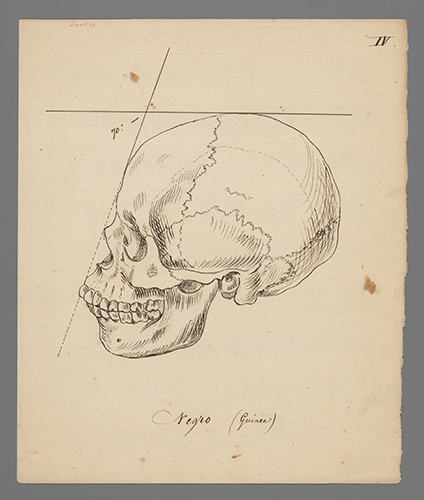

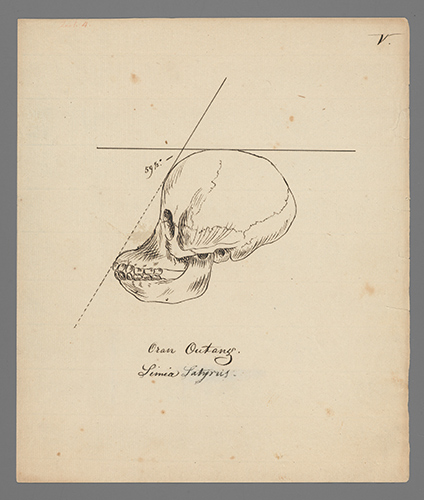

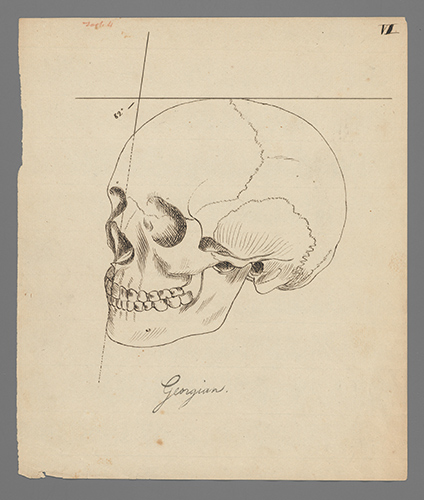

Before returning to reading Peck’s words, she paused on the illustrations, which she found quite jarring: five of them showed human skulls, and one showed an ape’s. Each was given a label, some of which were “Georgian,” “Negro (Guinea),” and “Oran Outang. Simia Satyrus” (meaning orangutan or chimpanzee).

Two years later, Robles began a curatorial internship at the Harvard Art Museums, working with Ethan Lasser, head of the Division of European and American Art and the Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. Curator of American Art. Robles’s internship involved work on the special exhibition that Lasser is organizing, The Philosophy Chamber: Art and Science in Harvard’s Teaching Cabinet, 1766–1820, which is set to open this May. The show will reintroduce a lost collection of art and scientific artifacts that were displayed from 1766 to 1820 in Harvard’s Philosophy Chamber, an early museum space. (For more on the chamber and what it held, read about the research conducted by curators, conservators, and other experts, in developing the exhibition.)

Robles was already familiar with the Philosophy Chamber, since she’d taken a course about it that was taught by Lasser and Jennifer L. Roberts, the Elizabeth Cary Agassiz Professor of the Humanities in the Department of History of Art and Architecture. She also contributed an essay to the forthcoming exhibition catalogue, about Peck’s flattened fish specimens and other flat materials in the Philosophy Chamber. But it wasn’t until she and Lasser started discussing the exhibition’s contents that Robles shared her knowledge of Peck’s skull drawings.

“We realized they gave us a window into the politics of the Philosophy Chamber,” Robles said. “They’re important to include because we believe Peck showed these drawings as part of his lectures, which were held in the Philosophy Chamber.”

Despite being relatively far into the planning for the exhibition, Lasser decided to add all six drawings to the display of art, instruments, specimens, and curiosities collected abroad. “Like all objects that were shown in the Philosophy Chamber, Peck’s skull drawings attest to a world in which art and science were interconnected and reinforced one another,” Lasser said.

Reproductions in a New Light

Harvard’s first Massachusetts Professor of Natural History, Peck was also a recognized naturalist and a skilled draftsman; many illustrations of flora, fauna, and other subjects accompany his manuscripts in Harvard’s archives. So it wasn’t exactly surprising to find illustrations that were presumably drawn or traced by Peck among his lecture notes. But the skull drawings—and the way Peck seemed to be interpreting and teaching about them—stood out.

“It seems at first glance that Peck was just reproducing three-dimensional objects on paper, but it’s actually more politicized that that,” Robles said. In both his drawings and lecture notes (which addressed the topic of mammals), Peck referenced the notion of the “facial line” and “facial angle,” techniques of both drawing and analysis that were developed in the 1760s by Dutch physician and anatomist Petrus Camper. Camper was one of the first thinkers to primarily use the internal anatomy of the skeleton rather than the external anatomy of skin color to describe racial difference. (Scholars debate whether Camper intended to use this method for racist purposes, but his ideas were certainly taken up in that way in the 19th century.)

Peck’s reference to the varied facial angles of the skulls implied a hierarchy of races, and the composition of his drawings backed up this notion. For instance, only two skulls, the African skull and the ape skull, were drawn in profile view, which set them apart as a pair; Peck sketched the other four in a three-quarter pose, suggesting that Africans were closer to “nature” than other human beings at a time when similar arguments were used to justify slavery and other injustices against people of color.

“By looking at these skull drawings, we get a glimpse into racial arguments that Philosophy Chamber professors offered to students,” Robles said. “It’s an important way for us to bring the discussion of race into the exhibition.”

Lasser added: “As drawings of specimens connected to racial science, these objects certainly raise unsettling and problematic questions about the curriculum in this period. The exhibition will give us a chance to study this complicated subject.”

Peck’s skull drawings also shed light on the types of objects that were included in 18th- and 19th-century collections. Both aesthetics and science were integral to each item displayed in the Philosophy Chamber. That concept is not necessarily true of modern-day art or science collections, which are often more starkly delineated.

For Robles, there have been even more takeaways from the experience of researching Peck’s skull drawings. That the works straddle the worlds of art, science, and society has been particularly exciting and will inform Robles’s own academic studies. “As a historian and someone who has previously worked in a natural history museum, I’ve found this project to be a way to leverage my skills in a completely new context,” Robles said. “It’s been fascinating.”