You’ll never find actual food in the galleries of the Harvard Art Museums. Representations of food, however, are abundant. Some of these objects were recently the subject of a two-part program about food in art organized by the Food Literacy Project, a student group run by Harvard University Dining Services, aimed at promoting a more complex understanding of food, both on campus and among the wider community.

Julia DeAngelo ’17, a sociology concentrator who is a member of the Harvard Art Museums’ Student Board and a fellow with the Food Literacy Project, came up with the idea for food-related programming at the museums.

“I wanted to combine the Food Literacy Project and the Harvard Art Museums in an event, so that students who are more familiar with one group could be better acquainted with the work the other group is doing,” DeAngelo said. “Both groups aim to educate and inspire students as well as the community, and to pursue ideas where there’s meaningful and important work to be done. I thought the two topics [food and art] would complement each other nicely but perhaps in an unexpected way.”

DeAngelo discussed her ideas and initial object list with Natasha Roule, a Ph.D. candidate in musicology, and Ruth Ezra, a Ph.D. candidate in the history of art and architecture, both of whom work closely with the museums’ Division of Academic and Public Programs. Roule and Ezra then extensively researched and prepared the content for each “food in art” session, drawing upon their own multidisciplinary perspectives to consider this creative approach to our collections.

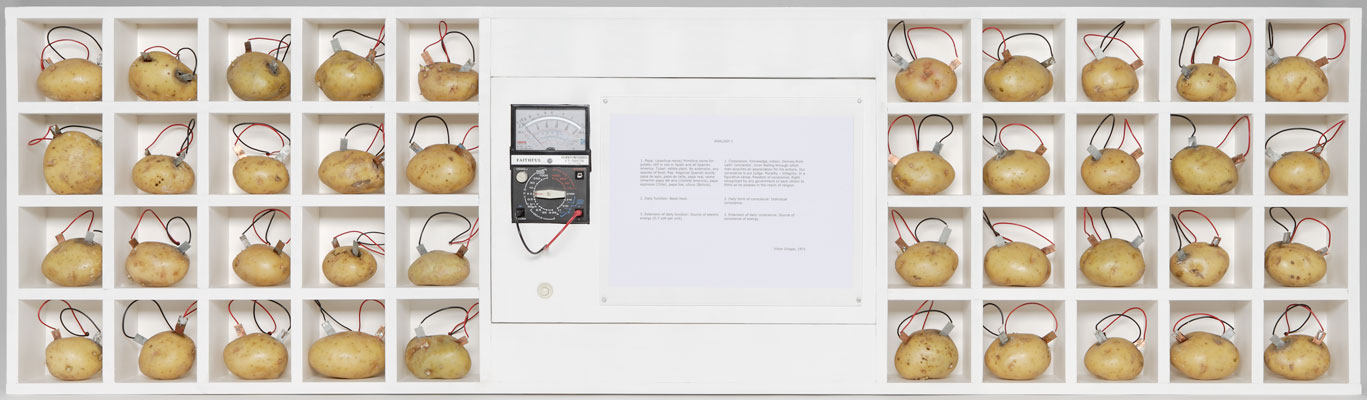

They began with a gallery tour that showcased diverse objects from each of our three museums’ collections and represented a wide range of time periods, cultures, techniques, and media. Ezra and Roule led participants through the galleries to look at works that depicted food or the process of gathering, preparing, or consuming it. Ezra spoke about alchemy and the transformation of food via actions such as cooking and drinking, while Roule focused on the social relationships that revolve around or arise through food. Among the stops were Sarah Miriam Peale’s Still Life with Watermelon (1822) and Victor Grippo’s Analogia I (1970–71). Rich discussion in the galleries raised new questions and ideas about food as subject, object, symbol, theme, and even, perhaps most unexpectedly, food as material.

Ezra and Roule brought a new set of attendees to the Art Study Center the following week, where they discussed six additional objects from the museums’ collections, including Claes Oldenburg’s False Food Selection (1966). The work consists of a wooden box containing various readymade fake foods, such as ham, eggs, and a banana. Though many attendees initially thought the items looked appetizing, closer examination revealed indications of rotting and spoilage. “Viewing Oldenburg’s work is really a layered experience, particularly as you spend more time with it,” Roule said. “It sparked a lot of debate.”

Andy Warhol’s iconic screenprint Chicken Noodle Soup (1968) also prompted discussion. “It’s an image that has become almost as ubiquitous as real cans of soup,” Ezra said, “but students are always surprised at its scale and level of detail when they see it for the first time.”

Because of the Art Study Center’s intimate atmosphere, Ezra and Roule were able to make visual comparisons between the works, physically positioning objects next to each other to help guide discussion. “We wanted to give people an experience with art that you can’t have in the gallery,” Ezra said, “and to introduce the collections as something anyone can access.”