Two works by acclaimed German artist Konrad Klapheck are now on view as part of the special exhibition Inventur—Art in Germany, 1943–55. The show focuses on art created while World War II was drawing to a close and in its aftermath, as Germans grappled with the conflict’s devastating consequences.

A Conversation with Konrad Klapheck

Klapheck, who was just 10 when war ended, saw in the destroyed cities and ruined buildings all around him a certain beauty or spectacle. His early drawings took up this adolescent interest, including the evocative Landscape with Ruins(1950), featured in Inventur.

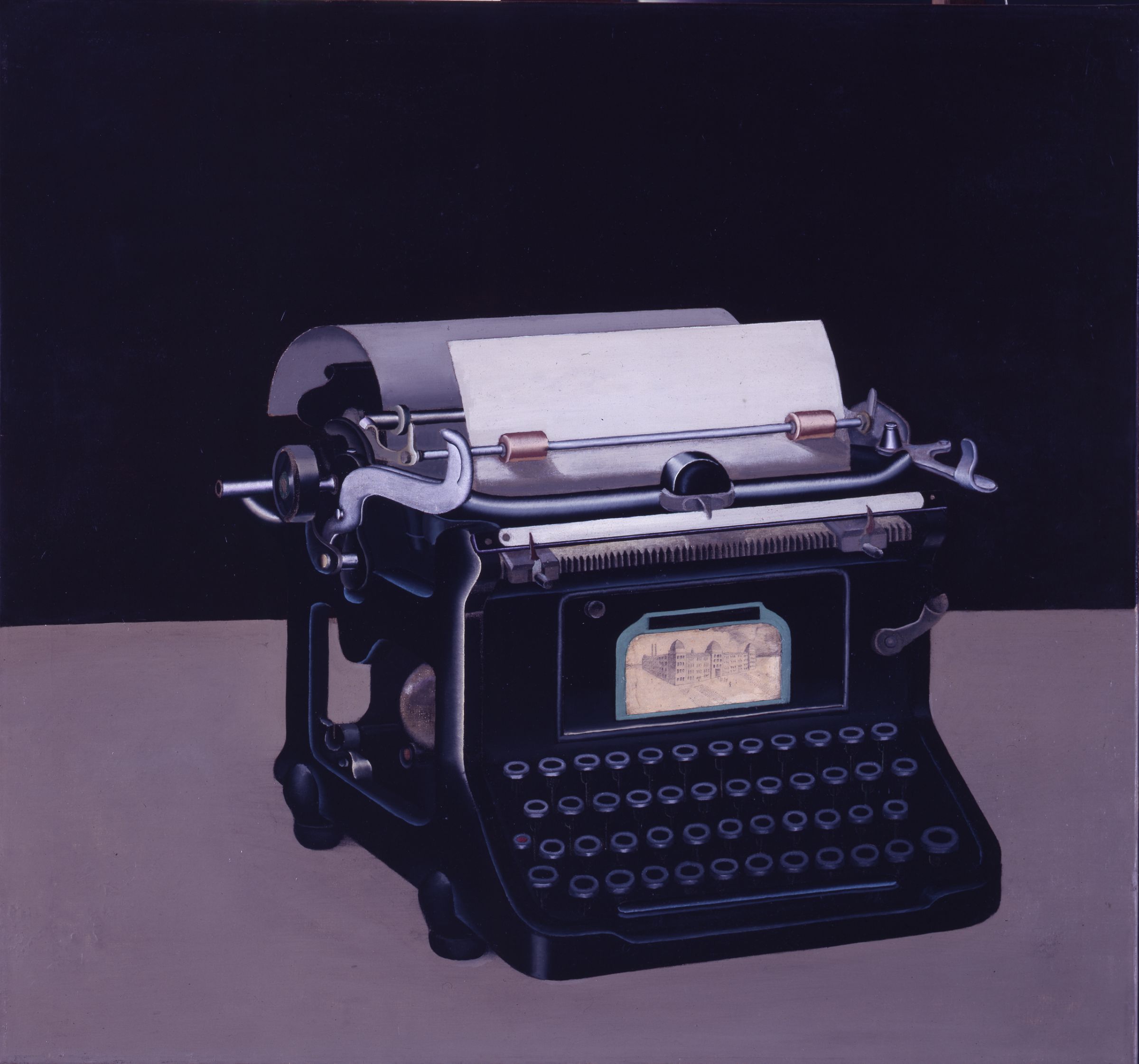

Later, once a student at the Düsseldorf Art Academy, Klapheck turned to a different kind of subject matter, creating the first of his many “machine pictures”: the 1955 painting Typewriter, also on view in Inventur. He went on to expand his repertoire to include sewing machines, faucets, telephones, irons, and even a hay-turning machine—as portrayed in Sketch for “Hero’s Chant” (1975), on view in the Busch-Reisinger Museum galleries. (Click here to watch a video of Klapheck discussing this monumental drawing.)

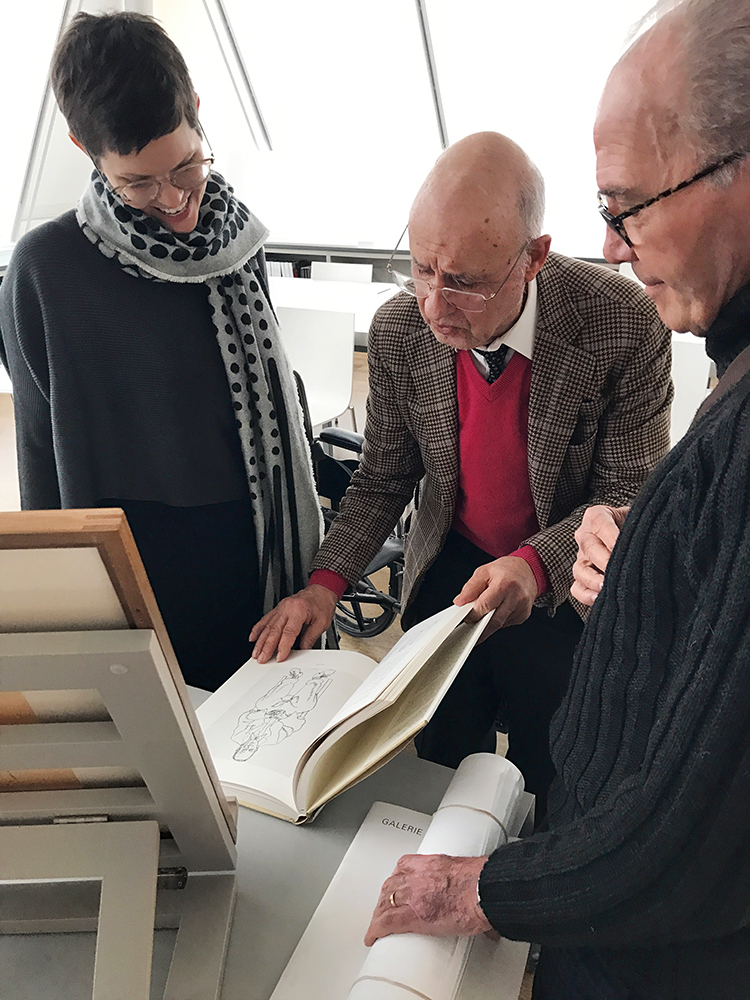

Klapheck, the only living artist featured in Inventur, spoke at the museums as part of the opening celebration for the exhibition, and led an Art Study Center Seminar with students about his work. During his visit, Klapheck took some time out to answer a few questions.

Index: Machines have been a major theme in your work. What about them appeals to you?

Konrad Klapheck: The interest was always there. It was this collaboration with the reciprocal influence of light and shadow. And I like that things look round and physical, corporeal. This is possible with machines. I started with small-scale machines: typewriters, sewing machines, and all the little machinery of the bathroom.

These [typewriters] are instruments used by politicians, by writers, by journalists. I did, all in all, more than 40 versions of the typewriter, always a different model. A different sort of viewpoint. So the machines became living people. It was . . . like classical theater, with different [archetypes]: the stingy father, the generous mother, the beautiful and sometimes cruel daughter of the stingy father, and so on.

Index: How did your experience growing up during the war affect your career and your art?

Klapheck: My childhood was partly happy, partly less, which is normal. My father died when I was four years old. But I was happy and had two parents who were historians of art. They were both professors at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. I grew up in the shadow of a fabulous library with the accent on books of art. At the age of seven, I was familiar with the work of the painters of the German Renaissance: Cranach, Dürer, Holbein. Others were still busy reading fairy tales or detective stories.

For me art was always present, and my mother was asked by friends, “How can you tolerate this? He will become a painter.” Oh, what horror, a painter. And my mother calmly answered, “If he wants to become a painter, I can’t tell him to become a dentist or a lawyer. The main thing is that he finds pleasure in what he’s doing, that he can identify with the works of art he is creating. If he wants to become a professional artist and if his talent is not to the task, he’ll be one of the first to notice it. So I won’t influence him.”

Index: Obviously, you pursued your dream and were successful.

Klapheck: I was privileged and I knew it and I enjoyed it. But art was misused by the Nazis. [When] I was born in 1935 . . . the Nazis had taken control of everything, especially art. Of course, there were artists, sculptors, some of them quite gifted, [who] . . . sold their souls to the Nazis. They were blinded by the idea of fame and fortune and wanted commissions and exposure.

Index: Do you feel your art is a reaction to that period?

Klapheck: Yes. There are a few paintings with typewriters and other instruments [in which] the scale and the angle from which the object is seen are exaggerated. One of those typewriter pictures got the title The Will to Power, the title of the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s book. In my work . . . there are paintings that have nothing to do with politics and others that are very much [related]. Sometimes it’s reflected in the title, sometimes the whole thing is inspired by . . . the governing idea of life and power.

Index: Can you describe the story behind Sketch for “Hero’s Chant” or Heldenlied, which depicts a hay-turning machine and is part of the Busch-Reisinger Museum collection?

Klapheck: Heldenlied translates to “hero’s chant,” or “heroic chant.” The idea [behind it] comes from illustrations of Greek legends with chariots of combat on stone vases. The great heroes, Achilles and Hector, [are pictured] fighting the star fighters of their armies, and fighting each other. “Heroic chant” [references] the songs of warriors, but with the idea that the warriors are from yesteryear, are long forgotten, and are underneath the surface of earth on which the hay-turner machine is working.

The word Held (“hero”) was essential for the Nazi time. Everything had to be heroic; this was the only really quality word: heroic. Here the word “heroic” exists too, but it’s broken, it’s ironic. And a friend of mine said, “Maybe you haven’t noticed, [but] you put a pun into your title. Change ‘chant’ to ‘song,’ [and you have] ‘heroic song,’ and change ‘chant’ to ‘camp,’ and it becomes ‘soldier’s cemetery.’” So the idea is, the machine works on top of the hills of earth, but underneath are buried yesterday’s heroes who are no longer alive. I said, “Maybe you’re right. Maybe there are some unconscious connections.”

Index: How does it feel to have your art featured in Inventur?

Klapheck: It’s a great honor to be represented at the Busch-Reisinger Museum and in this exhibition. It becomes quite clear that the work [created during a] certain period can reflect the surrounding conditions of political life and of human life in general.