It’s not every day that you can witness the transformation of dead insects into a renewable, non-toxic, and all-natural dye. But visitors to the museums’ Materials Lab recently had a chance to do just that.

A Colorful Tradition

Porfirio Gutiérrez, a member of Mexico’s indigenous Zapotec community, comes from a long line of weavers. His family is just one of a dozen in their village of Teotitlán del Valle that uses traditional techniques to create dyes for the yarn in their richly hued textiles. To produce a red dye, the weavers grind their own dried cochineal—parasitic insects found on the prickly pear cactus—into a powder, which they then combine with a few other natural ingredients. Their dyes derive also from about seven plant sources that, when combined and applied in various proportions, can yield 60 to 70 different hues.

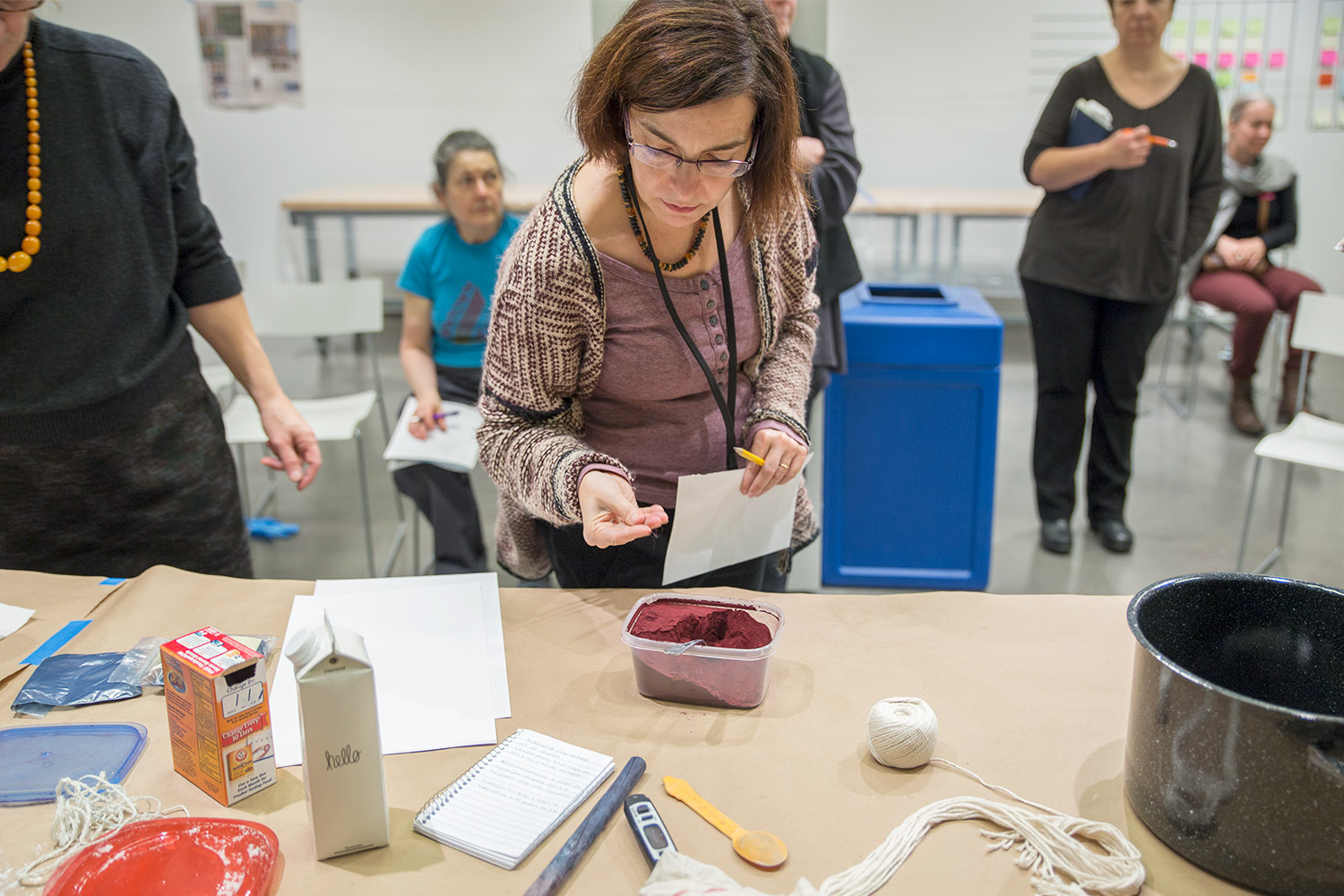

During a December visit to the Harvard Art Museums to lead a Materials Lab Workshop, Gutiérrez gave participants the chance to experience working with these natural dyes, including cochineal.

“Cochineal always surprises people,” Gutiérrez said. “A lot of people have heard about it but they haven’t seen it.”

During the course of Gutiérrez’s three-hour workshop, he led participants through every stage of the dye’s creation and usage, starting with grinding the pellet-like bug carcasses with a mortar and pestle.

“It takes nearly 70,000 insects to yield one pound of dye powder,” he told participants as they mixed the powder into boiling water to create a dark red solution. Next, they submerged white yarn, which had been pre-treated with a mordant to help ensure the dye’s permanence, in the solution. At the end of the session, they removed and wrung out their now vibrant red- and pink-stained yarn.

The hands-on demonstration complemented Gutiérrez’s recent donation to the Harvard Art Museums of five samples of Zapotec natural dye sources: cochineal, añil (indigo, used to produce blue dye), pericon (Mexican tarragon, used to make yellow dye), marush (a plant native to Oaxaca used to produce green dye), and huizache (a tree whose pods are used to make black dye). Gutiérrez also donated examples of yarn dyed with these substances, along with extensive written documentation about where each source was collected. (Many are hyper-local to the family; the notes for the cochineal, for instance, detail that it was “collected in our home in March and June of 2016.”) These materials were all added to the museums’ acclaimed Forbes Pigment Collection, an assemblage of approximately 2,500 historical and contemporary pigments, dyes, binders, and other materials used to make art from around the world.

“As keepers of this library of pigments, we think it’s fantastic to receive these types of samples,” said Narayan Khandekar, director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies and senior conservation scientist. “Porfirio’s samples are so well-documented—some samples can be collected from anywhere, but his come directly from his garden, from his family home, from the mountains around his village. They give us terrific insight into these sources and dye techniques and help us support the people who are working to preserve ancient traditions.”

Inherited Responsibility

Gutiérrez was raised in a family with a weaving practice that dates back to pre-Columbian times. One of his childhood memories, he said, is of his parents waking him and his siblings early in the morning and bringing them into the nearby hills to collect plants that would produce natural dyes. His parents remember having the same experience when they were young.

“People might be surprised to learn that there are still communities today where we carry on these ancient techniques.”

And even though this practice has likely survived the centuries among other families as well, knowledge of natural dyes is disappearing. “We don’t know how long this tradition is going to last because of today’s fast-moving technology and the [embrace of mass production] in our community,” Gutiérrez said. “We’re teaching our young people how to use natural dyes, which we hope means it’ll last a long time; but we don’t know what’s going to happen in the future.”

That concern is a large part of why he serves as a sort of spokesman for the natural dye process, and in particular for his family’s own textile production (their business is known as Porfirio Gutiérrez y Familia).

Like all 10 of his siblings, Gutiérrez was taught to weave at the age of 12—“that was just what we did,” he said. At 18, he moved to Ventura, California, where he held various restaurant and manufacturing jobs, before finally returning to Teotitlán del Valle. His homecoming after 10 years prompted an epiphany.

“I had this connection to my culture, but I also had this new perspective as an outsider,” which could be used to promote the family’s weaving production beyond their village, Gutiérrez said.

He also missed weaving. At that point, he said, “I made a commitment to weave again.”

Today he’s an accomplished weaver with a growing exhibition list for his textiles. His work was featured in a recent solo show at the Oaxaca Textile Museum. Gutiérrez splits his time between making and raising awareness of natural dyes by speaking and occasionally offering workshops around the country, such as the one at the Harvard Art Museums.

Only about 12 families in Teotitlán del Valle still use natural dyes, with just 5 or so employing them exclusively, according to Gutiérrez. It’s nearly as rare for families today to gather natural dye sources such as cochineal, Gutiérrez said. His own sources for cochineal are the farms of his nephew and another family in a nearby village, two of maybe 12 area farms harvesting the insect.

Participants in Gutiérrez’s workshop were fascinated by such details. One wondered about the origins of the practice: “How did anyone even think of this in the first place,” she mused. “Like, hey, you can grind up this insect to make a powder and then use that as a dye?”

“We don’t know,” Gutiérrez said as he helped another participant stir a dark blue dye solution made with añil. “Our ancestors were clearly great chemists, artists, and architects. I can’t imagine how long it took to perfect this technique.”

His own work, he said, pays homage to those textile masters, by putting a contemporary and personal spin on traditional designs. Gutiérrez recently began creating a body of work he refers to as fragments, which attempt to represent symbols and motifs of Zapotec culture that have endured since before the arrival of the Spanish; he has also experimented with using historical weaving materials such as plant fibers.

Meaningful Display

The gift of the Zapotec dyes and their plant and insect sources to the Forbes Pigment Collection is another way that Gutiérrez hopes to honor and preserve his heritage. He imagines that a future member of his community who may lack knowledge of natural dyes could one day turn to this resource, particularly if the tradition disappears among the Zapotec. And, he said, it could even spark curiosity among current visitors. “People might be surprised to learn that there are still communities today where we carry on these ancient techniques,” he said.

Museum visitors can view samples of his natural dye sources and yarn in a temporary installation of recent additions to the pigment collection, in a display case near the Art Study Center reception desk, on Level 4.

Already, the samples in the case have prompted plenty of interest among visitors. Cochineal in particular is a conversation starter, said Charlene Briggs, a receptionist at the Art Study Center, who frequently fields questions about the display.

For Khandekar, the display case is an ideal way to show visitors “the stuff that art is made of,” whether natural or synthetic. “It’s like looking at atoms,” Khandekar said. “When you put together a bunch of atoms, you can see what amazing things they can do. It’s the same for pigments and binding media. These are the fundamental particles; you put them together and you end up with something really spectacular.”