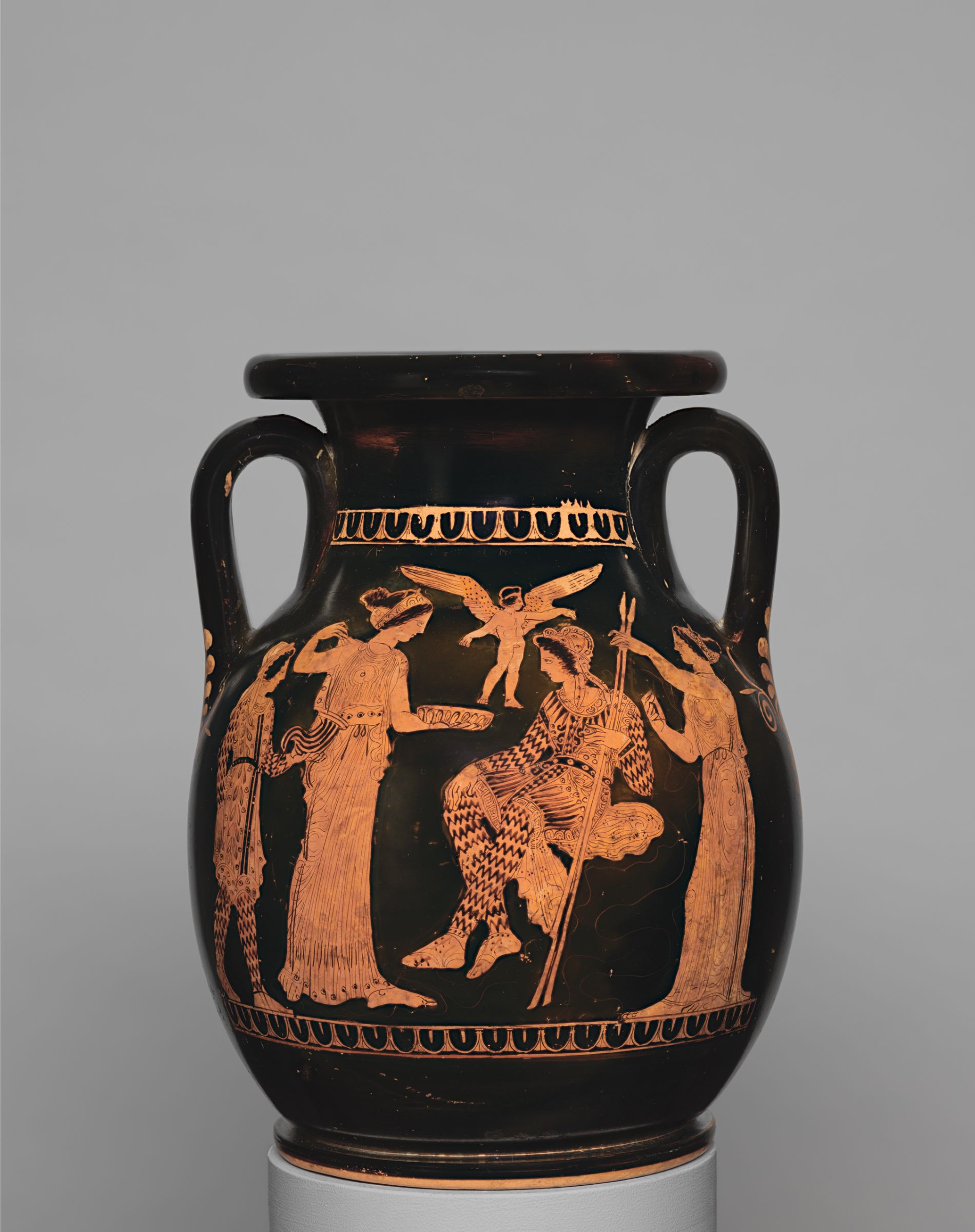

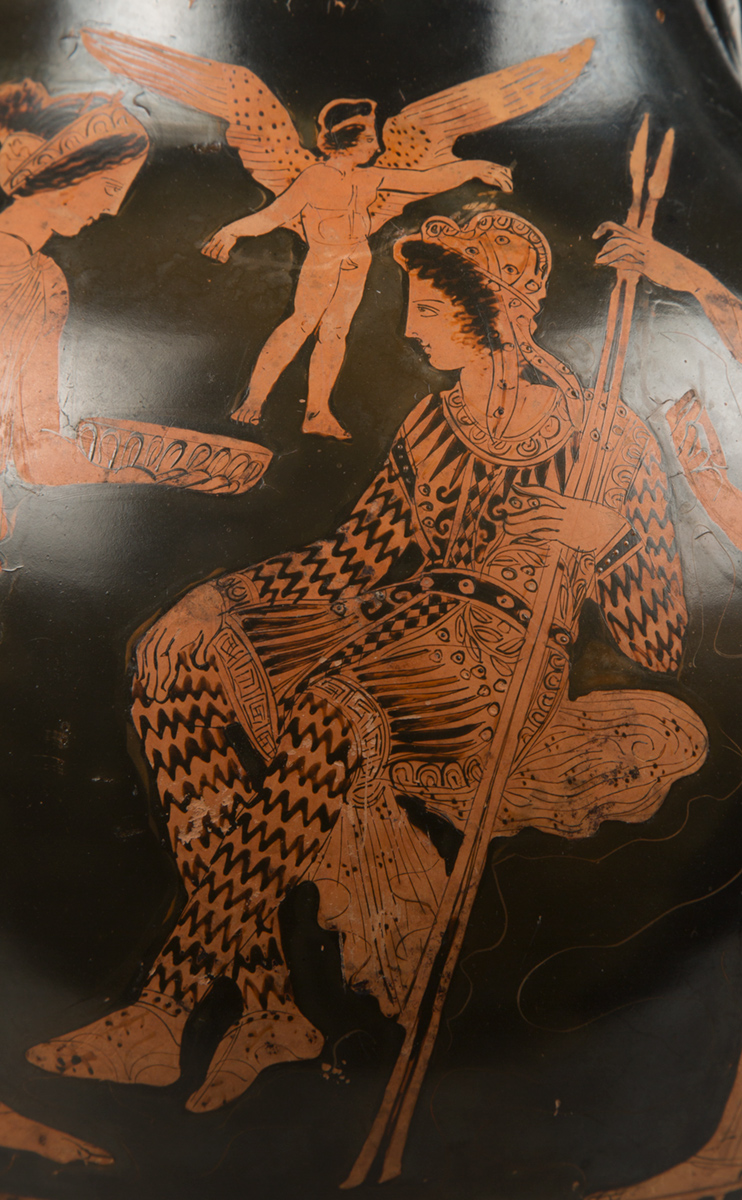

Today, burial accretions such as these are often allowed to remain on objects and are accepted as part of their archaeological history. However, this Greek jar was in otherwise pristine condition—it had never been broken, which is rare for an ancient terracotta vessel. Therefore, said Costello, “we wanted to remove the stains to help make the interpretation clearer for the viewer.”

Research and Experimentation

There was just one problem: barely any literature existed on reducing manganese staining in objects like ancient Greek ceramics. “We were basically starting from scratch,” Costello said.

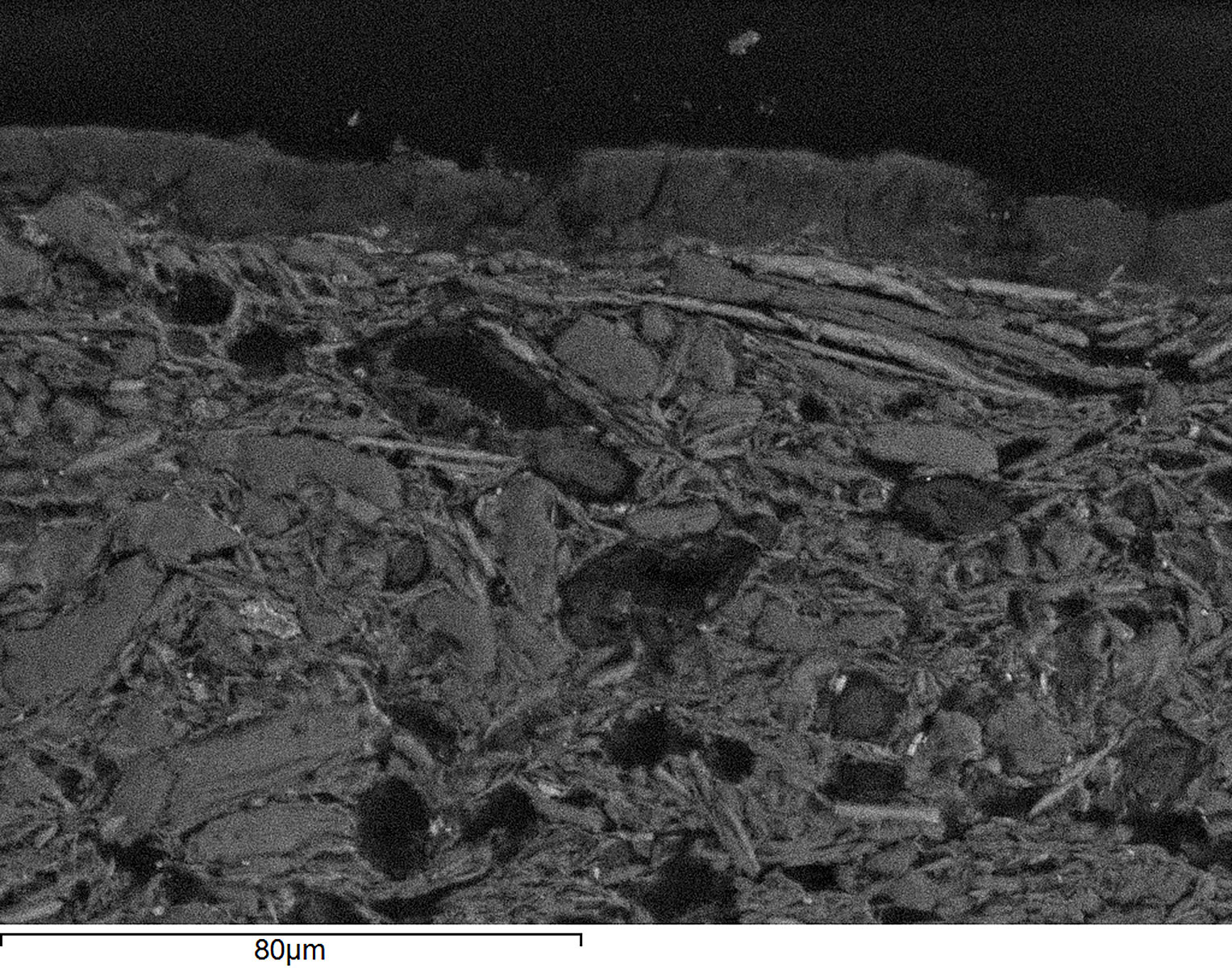

She and her colleagues realized they would have to identify a stain-reducing agent through trial and error, using mock-ups. They created terracotta pieces with artificial staining in the Straus Center’s objects lab. The team was also able to conduct tests on a small portion of an ancient terracotta plate from the museums’ collections that appeared to have similar manganese staining, and on the underside of the jar itself (a surface rarely seen by anyone but museums staff).

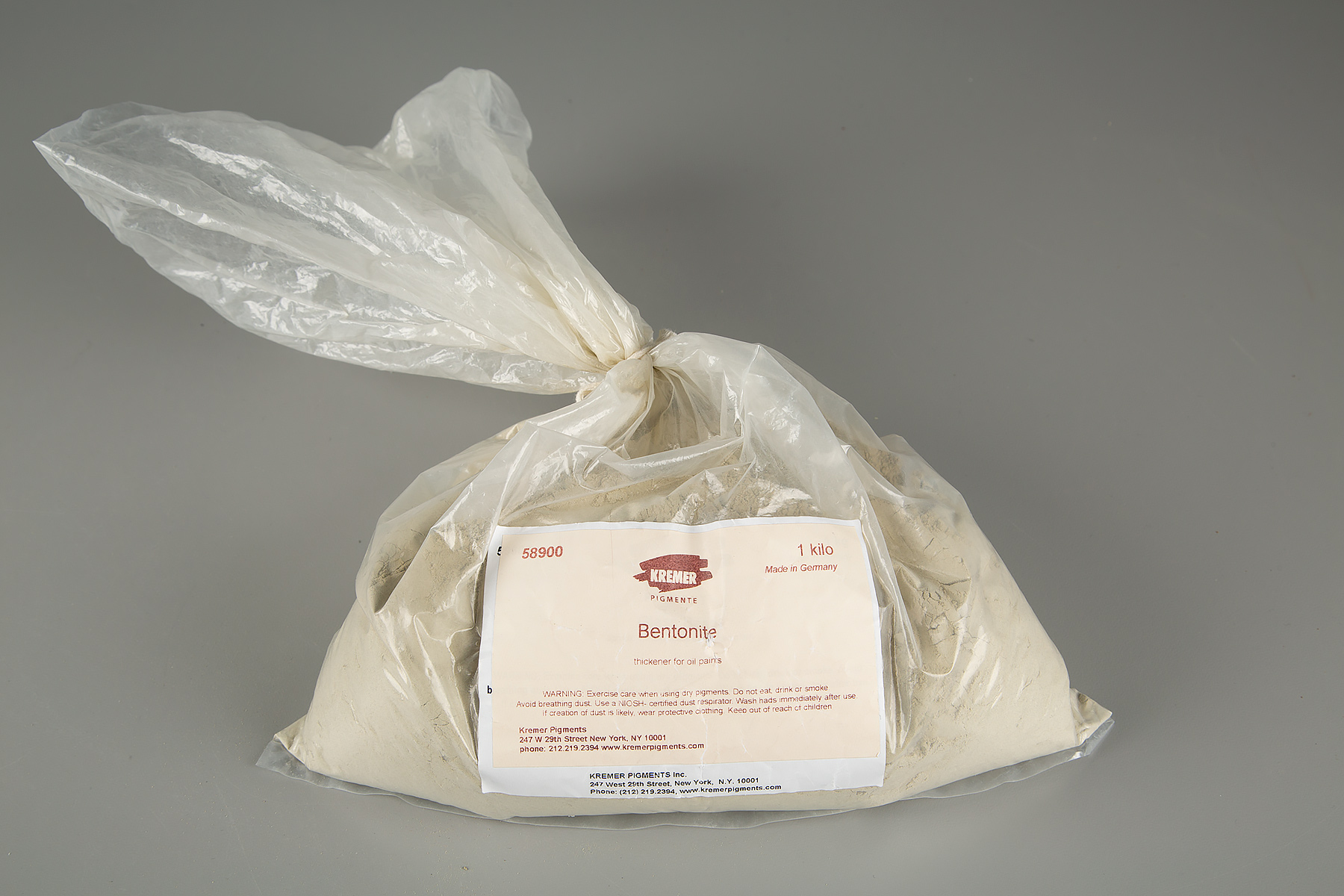

In efforts to break the stain’s bond with the ceramic, the conservators tested a variety of chemicals, but had no success. Then, they thought to try to remove the manganese’s bond by applying a material with a high ion-exchange capacity to encourage the manganese stains to exchange their cations (positively charged ions) with those in the newly introduced material, which would then release the stains.

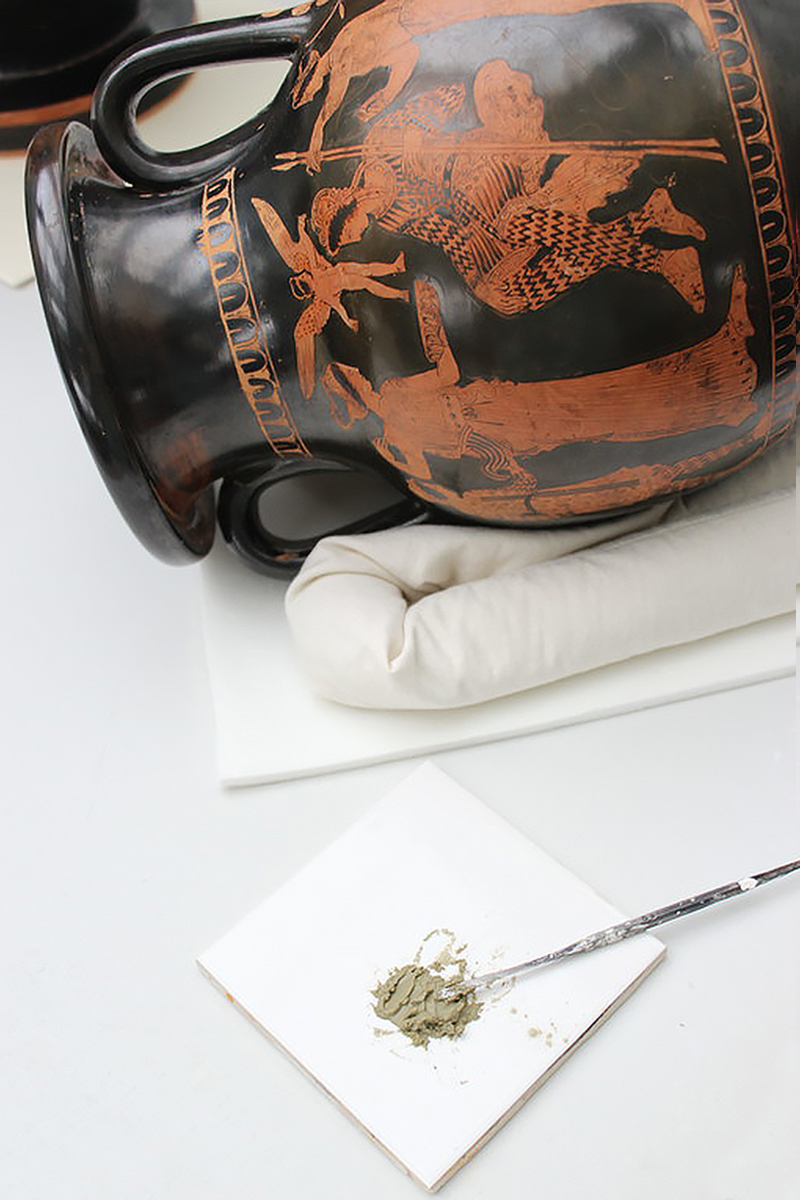

A natural clay called Bentonite fit the bill. “We mixed the clay with deionized water to create a poultice, applied it to the surface of a stain, and covered it with plastic, which slows the drying process, to allow it to dry overnight,” Costello said.