Before Maurice Wertheim (1886–1950) started collecting art, he had already established a successful investment firm, bought the flailing magazine The Nation, founded the New York Theatre Guild, and pursued his love of chess.

When, at the age of 50, Wertheim turned his eye toward art, it is no surprise then that he approached it with as much zeal as he had his other interests. Fourteen years after his first purchase—Picasso’s The Blind Man (1903)—Wertheim had amassed a stunning collection of impressionist and postimpressionist paintings, drawings, and sculpture. Among them were works by Cézanne, Degas, Matisse, Monet, Renoir, Seurat, and van Gogh.

To the delight of the Fogg Museum’s Associate Director Paul Sachs, Wertheim (Harvard Class of 1906) bequeathed the entire collection of 43 works to Harvard University. But there was one stipulation. The collection must always be shown together as a group. So when the collection was taken off exhibit two years ago in preparation for our reopening, curators and conservators relished this rare chance to work on it behind the scenes. They could now update the scholarship and perform much-needed conservation treatments on these prized objects—which will in turn inform the way curators present the collection in the new Harvard Art Museums.

“It has been a thrill for all of us to examine the Wertheim Collection closely, while humbly seeking to consider it from new perspectives and in new contexts,” says Elizabeth Rudy, the museums’ Theodore Rousseau Assistant Curator of European Paintings. Rudy is coordinating the ambitious research project, which has already borne fruit.

Rich Results in Conservation

Because most of the paintings had never been X-radiographed and none of the sculptures studied by conservators, the team in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies is making extraordinary advances.

Dina Anchin, our current Paintings Conservation Fellow, for example, is in the midst of a revelatory project on Seurat’s Vase of Flowers (c. 1879–81), a rare example of the artist’s pre-pointillist work and his only known still life. She is finding that Seurat may have made several changes to the composition—X-ray images digitally superimposed on the color image indicate that he changed the shape of the flowers and the position of the table. What is most intriguing about the work, though, are the clumps of paint on the top and right edges of the canvas. Perhaps they are excess paint that Seurat wiped off his brush or evidence of compositional changes. Anchin is eager to find out what her explorations will suggest for future treatment of the painting. (See Anchin’s conservation images below and the photo story on Flickr.)

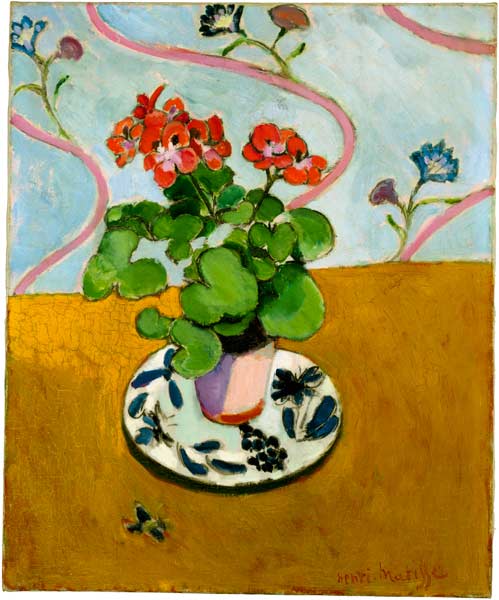

Former Paintings Conservation Fellow Gabriel Dunn discovered multiple reworkings by Matisse in Still Life with Apples (1916) and Geraniums (1910). X-ray images of Apples showed that the artist had made changes to the apples, glass, and the angle of the table. Analysis of paint cross-sections in Geraniums showed his experimentation with color: he revised the wall and table colors multiple times, from pink to blue or red to green, for example. Both works have benefited from conservation treatment, as well. Dunn removed a varnish from the surface of Geraniums, which clarified the colors throughout. Frame conservator Allison Jackson removed the linen from the wooden frame liner of Apples and gilded it, creating a more striking, harmonious presentation.

Kate Smith, Project Paintings Conservator, uncovered many details about Monet’s process when he created his masterpiece The Gare St. Lazare; Arrival of a Train. What gave her a thrill was finding, through X-ray images and an examination of paint layers, that he didn’t initially plan the train on the right, but added it late in the painting process.

A Wertheim Study Day

While so much has been accomplished, there is still much to do, and not much time to do it. Elizabeth Rudy has been instrumental in keeping curators and conservators engaged in the project. To help them view the works from fresh angles, she organized a study day last year, inviting outside scholars to put the works in context.

The talks proved to be inspiring and informative. For instance, a Renoir specialist helped answer questions about Renoir’s later work (the collection’s Gabrielle in a Red Dress is from 1908). “I wanted to find out why we should pay closer attention to his paintings in the collection,” Rudy explains. “His late work is so maligned, and I felt we weren’t appreciating what other artists had seen in him. Matisse was devoted to Renoir, as was Picasso, who thought Renoir was revolutionary for his late work.”

Overall, the study day not only helped reenergize the museums’ own efforts, but, according to Rudy, it served a larger purpose, “to share our work with eminent scholars on this important collection through lively discussions and debates, which will continue beyond the reopening of our museums.”

See more conservation images of Vase of Flowers on Flickr.