When Maja Wismer came to the Harvard Art Museums in September to select multiples by German artist Joseph Beuys for display in the new building, she knew the task would be enormous.

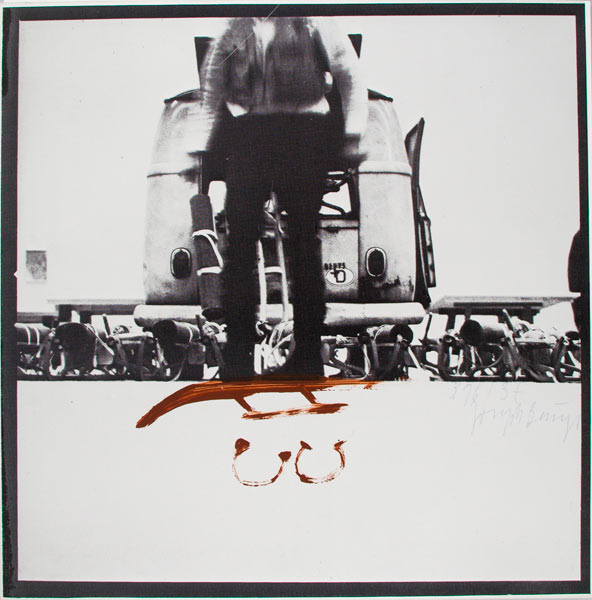

Maja, who is the Renke B. and Pamela M. Thye Curatorial Fellow in the Busch-Reisinger Museum and is writing her PhD on the subject, will be curating a series of six to ten thematic installations. She’ll need to choose from our near-complete collection of 600 multiples, which are editioned objects, prints, photographs, and postcards. Because Beuys (1921–1986) worked with such diverse media as fat, felt, and chocolate, she knew she’d have to collaborate with the conservation department to determine which objects could be treated in time for the opening. But she didn’t know that an object she was especially drawn to would require the most extensive treatment.

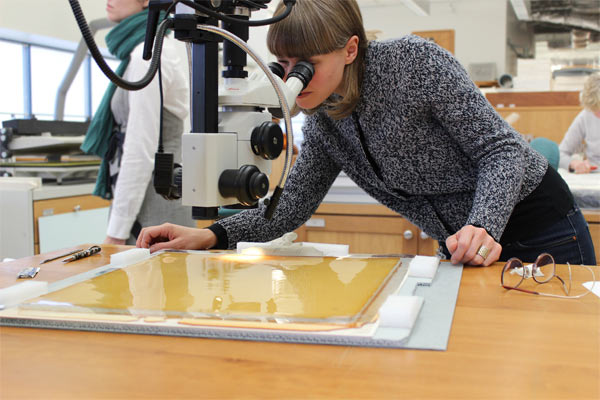

In her search for appropriate objects for exhibition—which requires considering how multiples relate to one another and to other works within the galleries—she found Beuys’s Phosphorus-Cross Sled (1972) crucial to include to help contextualize the multipleSled (1969). She invited Nicole Ledoux, the Samuel H. Kress Object Conservation Fellow, to the storage area to look at the object together. When they opened the box, the level of deterioration surprised them, and they realized that they would need to devise a conservation plan for display and long-term storage for this piece.

“We expected that the multiples composed of materials such as fat, felt, and sulphur would be the pieces showing the greatest need for conservation, but not really. It was the plastics,” said Nicole.

Though Beuys was very interested in ageing processes, which is why he often worked with organic materials, Maja suspects that he did not intend the plastic to change over time, simply because no one expected it to. “In the 1970s, plastic was an exciting new material and, of course, it always looked brand new—it looked great, it looked cool. Nobody considered this to be something that wouldn’t stay the way it was, that it might turn into something dangerous.” Deteriorating plastic, as it turns out, can produce volatile byproducts harmful to humans and objects in its vicinity.

Rather than a hiccup in the process, this discovery has led to an incredible opportunity. Not only will Nicole take on this project to study and conserve the plastic Beuys multiples, but the Harvard Art Museums’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies can apply the resulting treatment strategies to other works in our collection made of similar materials. Maja says that other museums with contemporary art collections are facing the same challenges. “For instance, [Robert] Gober is another artist whose work continually raises conservation concerns because of [his use] of wax. How to keep these materials and how to store them—it’s a very lively discussion at the moment.”

Another rewarding aspect of the project is the collaboration between Nicole and Maja. Though their backgrounds are strikingly different—Nicole’s experience has primarily been in conservation of anthropological collections and Maja’s is in contemporary art—their collaboration makes perfect sense. Nicole was drawn instantly to Beuys’s use of unconventional materials, which are often found in ethnographic objects. The Beuys project has satisfied her desire to work with contemporary art. And Maja is thrilled to be able to rely on Nicole’s expertise to gain deeper knowledge of Beuys’s materials.

In the end, Nicole says, they are working toward the same goal: “to devise a strategy for storing these pieces for the long term and for exhibiting that specific piece [Phosphorus-Cross Sled] in a way that’s safe for people, for the object, and for the other objects in the [display] case—and still have an arrangement that works.”