Curator Makeda Best recently talked with photographer Mariette Pathy Allen, who created a groundbreaking portfolio focused on crossdressers in the 1980s. Now 80, Allen explains the circumstances and artistic processes that shaped the work, which is preserved in the Harvard Art Museums collections. Allen Frame, a friend of the artist and a photographer himself, also joined the conversation.

Mariette Pathy Allen’s books include Transformations: Crossdressers and Those Who Love Them (1990), The Gender Frontier (2003), TransCuba (2014), and Transcendents: Spirit Mediums in Burma and Thailand (2017). She has worked on numerous films as well as radio and television programs about gender topics, and has given lectures around the world. Learn more here.

Makeda Best: Could you tell us about your early career? What drew you to photography?

Mariette Pathy Allen: I was a painter first. I became a photographer only after graduating from the University of Pennsylvania. By fluke, I met a photographer named Harold Feinstein, and it was through him that I started to do photography. I got a couple of wonderful jobs right at the beginning of my career. One was to photograph artists in the Philadelphia area for WCAU-TV. I also got a job working for the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton. There, I was asked to photograph “The Face of New Jersey.” The curator had just seen [the MoMA exhibition] The Family of Man, and he thought New Jersey should have something like that.

Around 1969, I moved back to New York. I continued to paint, but I also started photographing in color—flowers and fantasy. And then, in 1978, my husband and I went to New Orleans for Mardi Gras, and we stayed in the same hotel as a large group of crossdressers who were there for the parade. On the last day, I went down to breakfast, and there they were. This incredible group of people were very friendly, and they invited me to join them for breakfast. Outside the dining room, there was a swimming pool. They started parading around the pool and someone started taking pictures of this lineup, and I thought, maybe it’s okay if I take a picture. So, I lifted the camera to my eye and, looking through the lens, I saw that the person in the middle of this lineup was looking straight at me. I said to myself—it just came to me—I’m not looking at a man or a woman, I’m looking at a human being. I’m looking at a soul. I took the picture. I said to myself, “I have to have this person in my life.”

It turned out this person, Vicky West, lived about 20 blocks from me in New York. That is how it all began. Vicky took me to all the events that she went to. Ultimately, she took me to Fantasia Fair, which is where it all really took hold. I started to learn more about this phenomenon and how to photograph people who had never been photographed in a positive way, by anybody. That was a huge learning curve for me. Suddenly, I realized I’d been given a huge gift. I began to feel like I was the conduit through which information could be disseminated about people who had been degraded, who had been considered evil and dangerous, who had not been allowed to go to their churches, who’d had to hide from their spouses and certainly their children. Some of them even grew up thinking they were insane, because they didn’t know anyone like themselves. The more stories I heard, the more pictures I took, the more I continued to work. I saw no reason to stop. As the community evolved, I continued to participate in its trajectory.

MB: At the time you started making the photographs, were you aware of how transgender people were made to feel in society? How much was that awareness part of how you pursued your work?

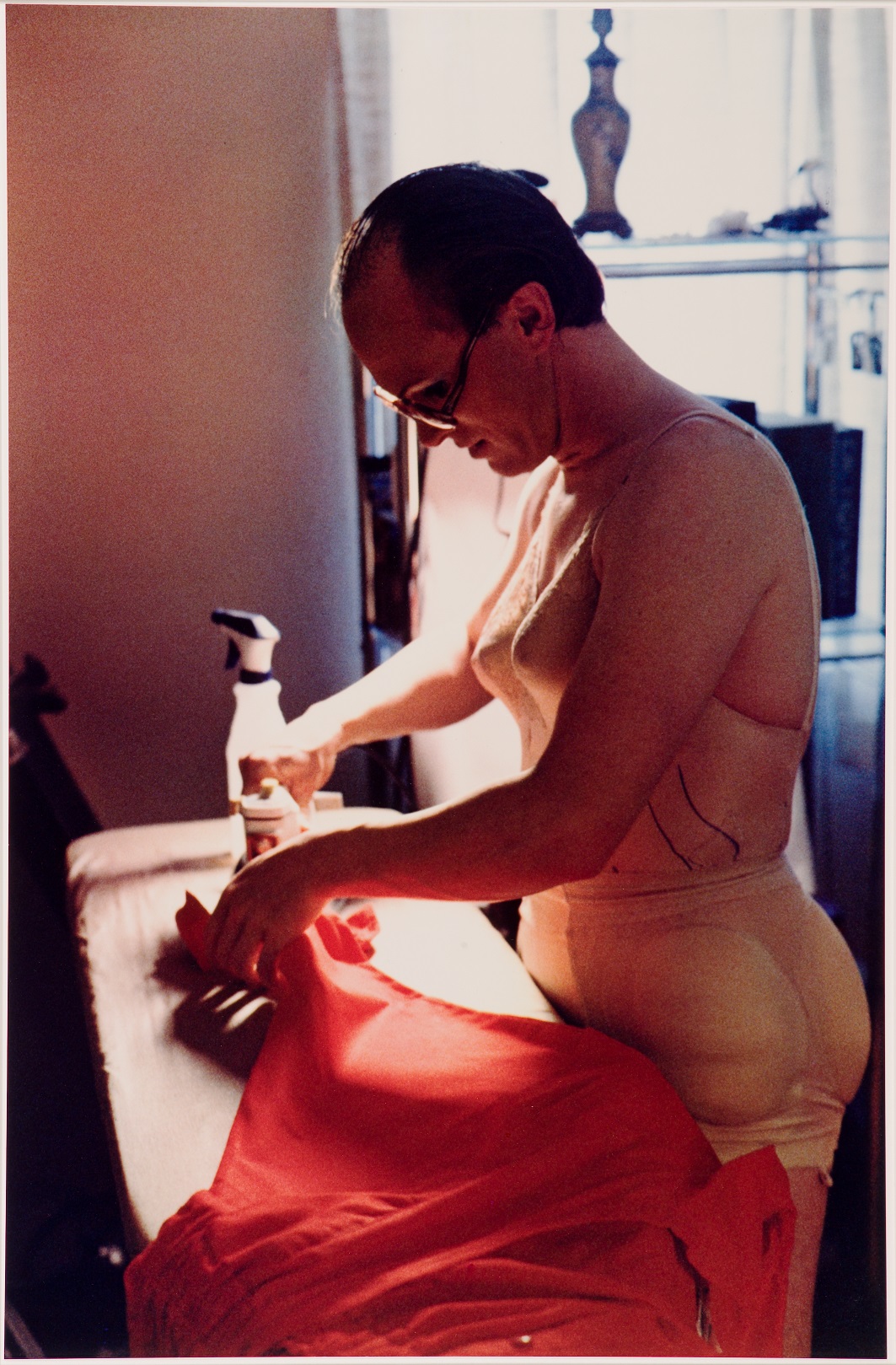

MPA: In talking to transgender people, I became aware that they couldn’t find images that they related to. The images they could find were in porn shops or academic books. And those books were always for the doctors and psychiatrists who looked at them objectively, often in the nude, not from the perspective of care or of help, but as a source of scientific and medical knowledge. The crossdressers didn’t identify with this imagery. They often pointed out to me that they weren’t gay, contrary to the general assumption. They weren’t interested in being depicted as creatures of porn or being scrutinized. I learned that anatomy, gender identity, and gender expression were separate issues that could be combined in any form.

When I was in high school, I was lucky enough to take a class in cultural anthropology. The course made me question something about myself. I never understood why men were supposed to have certain characteristics and women to have others, and why these were the implied rules of our society. I didn’t understand that, and I felt rebellious. And then, when I met trans people, I had a great sense of relief, because I realized it was true that gender didn’t always go according to the “rules.” But I had a lot to learn.