Makeda Best: Maybe we can start with what brings you here. For me, it’s important I use my work to expand the circle of voices in discussions about art. This installation project is really a celebration of the role different voices can play in the museum space and elevating the insights those voices bring to the objects.

Archy LaSalle: Most of you know that I’m deeply involved with the organization that I spearheaded and founded called WHERE ARE ALL THE BLACK PEOPLE AT. We are all here. All you got to do is look around and you see us. As an educator, I was frustrated with the fact that so many times I would take my students to museums, and they would not see themselves. Meanwhile, I look at museums’ mission statements versus what they’re doing, and most museums and art institutions do not reflect what I think they should be doing for youth and for the community. WHERE ARE ALL THE BLACK PEOPLE AT came about because of those experiences.

I’ve often heard curators talk about these kinds of photographs, and they say, “We haven’t seen these before.” And I always think: Wait a minute, I’ve seen those photographs. I grew up with these photographs.

L’Merchie Frazier: Just dovetailing off what Archy has offered: as director of education and interpretation for the Museum of African American History for 20 years, I’ve worked to develop the education department for that museum, and to establish opportunities to expose people, especially our youth, to our history. I want to give them what they don’t get in their classrooms and help teachers be able to teach this history, which is hard and tough stuff.

Desiree Ivey: I learned a great deal about the impact art can have on who you are as a student at an HBCU [Historically Black College and University]. I remember Professor James Lewis at Morgan State University, who was the director of the art gallery there. At the time I was at Morgan, the Walters Art Gallery featured an exhibit called The Image of the Black in Western Art. I had never before seen such an exhibition. That was part of the reason why I wanted to be a museum educator. I wanted to be like Professor Lewis.

Jade Burns: This is all relevant to my work and my research into how images play a role in people’s understanding of healthcare. I spent many years in cities providing care as a nurse and a nurse practitioner, and then I went back and got my Ph.D. Images are important—if providers don’t look like you, you don’t want to come in. This also relates to this project. It took you to see this painting differently and to see these photographs in dialogue with the painting.

MB: When I think about Negro Solider, I wonder why it is always about what is supposedly unknown. I’ve said exactly what Archy said before: We know who he is. We know his community. We know this.

Dosha Beard: I am very inspired by everything I’m hearing. Brother Archy said that going to a museum should be like going to a supermarket. We should be seen all the time everywhere, not just in the month of February. I have a particular problem with Black History Month being the shortest month in the whole year. You had to find the shortest month to give to honoring what the history of Black people have contributed everywhere. It’s not fair. So I try to promote Black history all year long. All you need is to be reinforced in some way, whether it’s through humor or art. It needs to be instilled in us. And we shouldn’t have to go digging for it. So, I hope this is the beginning of something. I remember the Museum of Fine Arts had the Quilts of Gee’s Bend exhibition, and oh my goodness, wow. That made me pull out my quilting things again and start to go back into that. I’m not a photographer. I might become one, though, because one thing I like about these photographs is looking at the subjects. It really cracks me up. Some of the people in the photographs are smiling. The looks on people’s faces tell so much about who they are inside.

Richard Haynes: I want to say that art institutions have been backward for many years. They are the most significant cultural keepers and culture makers, but I don’t think they understand it.

What caused me to start painting the kinds of things that I paint and photograph is that I didn’t see myself in positive images. You go to a book and look at the vaudeville era. You look at the Jim Crow era; man, we are buffoons. I decided to move to New Hampshire 39 years ago. I thought I would be a face in this small community, but I became faceless in this community. And faceless to a point where I decided I don’t like this life, I’m about to check out. And thank God I had a spiritual intervention that said: No, I got you where I want you, but now I’ll make you who I think you are. And what I started doing was painting. I promised this divine spirit that I would forever paint the story of the faceless people in this society until I die. It’s an American story, and we as artists must remain optimistic, remain disciplined, and keep doing the work because one day the country and the institutions who are cultural keepers and makers will begin to wake up and truly see the importance of our contribution to America.

“We should be seen all the time everywhere, not just in the month of February.”

Archy LaSalle: One of the things that caught my eye right away was the different formats and types of photographs.

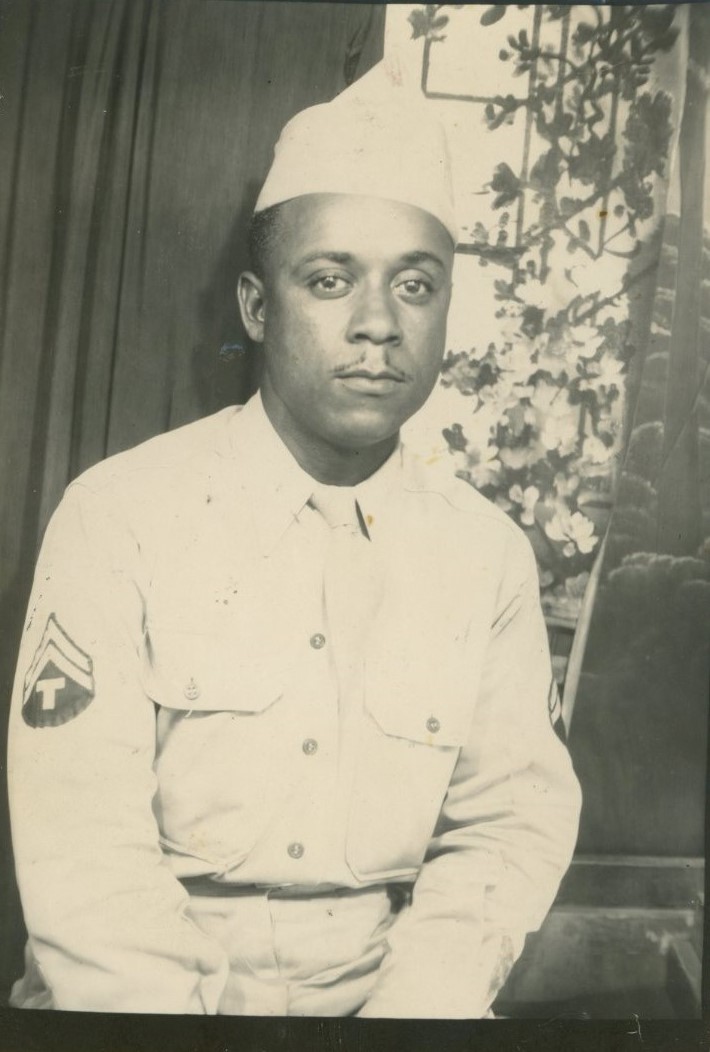

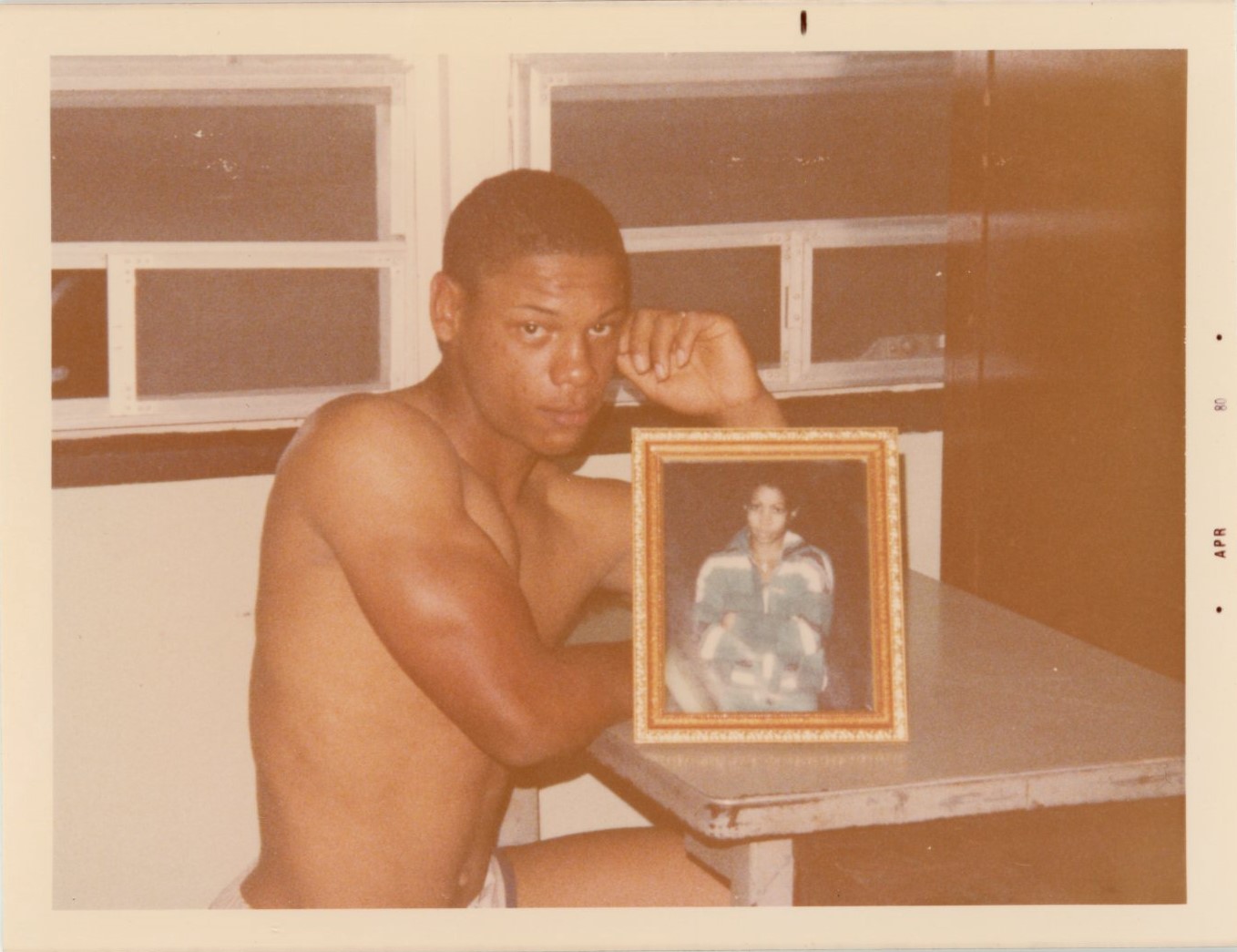

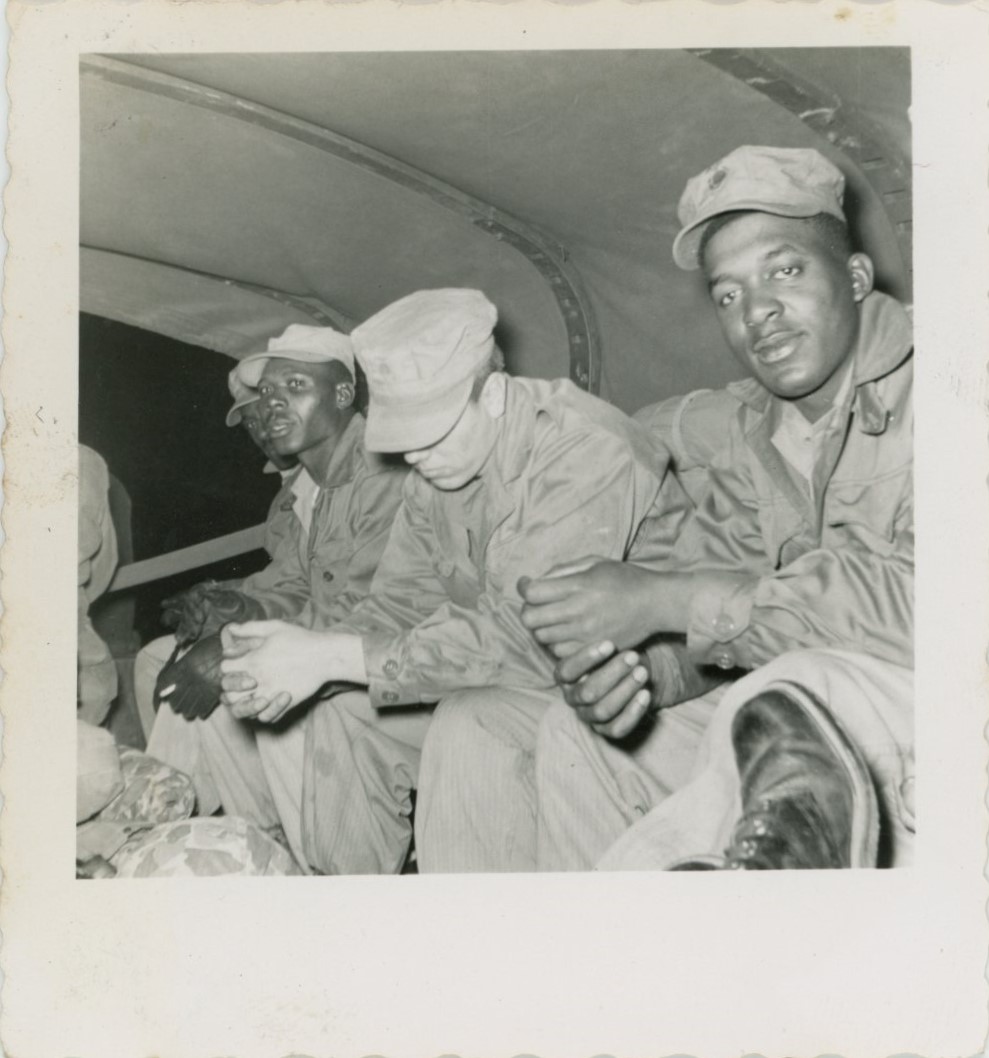

MB: These photos are from people’s homes. These were part of people’s lives. The Robert Smullyan Sloan painting was displayed in the Carnegie International Exhibition where it won medals in 1948. Recently, there has been interest in the sitter’s identity and on how to figure out who he was.

I began visiting a collector of vernacular photographs in the fall of 2019, Peter Cohen. I was seeking images about African American military service. At first I sought images from the same time period of the painting, but then I expanded the selection to emphasize the broader historical context of service to which the unnamed soldier belongs. I expanded even further from military service to everyday life, because he had a family and a community. I wanted the collection of photographs to portray his world, a world in which I also see myself.

In Sloan's painting, there seemed to be a way in which the soldier is frozen in 1945, but metaphorically, the photographs show us he isn’t frozen. He wasn’t “born” in the time of the painting’s construction. And he didn’t come from nowhere—so it goes both ways.

When you look at this painting, what are you curious about, or what’s a detail that you think is interesting. I focus on his gaze or his eyes, and the kind of urban background behind him makes me wonder where he is and what his relationship is to the outside world.

George Annan: His gaze shows he’s not 100 percent at ease—there’s a little bit of hesitancy. And I would say even during the time period in which the painting was made, it’s almost like he needs his family, his community, to adapt to the world that he is returning to.

I can sense from this painting that it’s like he’s fighting two wars at the same time: both the wars overseas and also the war in this country against racial discrimination. I think all those worlds are hitting him at this moment, and the painting captures this feeling of, All right, how can I adapt to the current climate in 1945, and how can I best support myself and my family?

Dosha Beard: That’s right. Exactly. And he has that look like he doesn’t really trust this scenario. It shows the distrust that most of us have had to endure over the years, whether it is an [accurate] representation of society. I love the amount of character in the subject’s face.

Jade Burns: I feel like I’m there with him. You feel like you’re sitting in the room. We’ve already mentioned his unease, his discomfort. I like the details in his uniform, because you can actually see all the intricate pieces of it. It seems too real almost.

L’Merchie Frazier: It is very well executed. There’s a relationship between the person who is being portrayed and the artist, and what is that relationship becomes my question. I’m also interested in the light and how light is brought into this image. It highlights the indentations in the wood window frame, and the light suggests the time of day. The light is also reflective of the training of the artist. But the story here is one where the viewer brings the questions to the conversation, so that makes it a very thrilling kind of portrayal.

Desiree Ivey: I’m also finding it interesting that the artist has signed this painting with his first, middle, and last name, and the title of it is Negro Soldier. So I’m intrigued by the contrast there.

Archy LaSalle: On a broader level, that is his name: “Negro Soldier.” It’s all the things that we’ve been talking about: they didn’t see us, they don’t see us, and it’s up to us to see us. We know whoever has control of the printing press determines what’s being recorded.

This artist spent so much time with this individual, and he couldn’t even ask his name. I mean, what does that say? Let’s look at the clouds. You see the blue sky in the background, all that detail. This person can come up with so much detail, but you can’t find the person’s name.

Richard Haynes: Although he may be faceless in society, the rendering of his face has made him visible. Don’t forget, as a Black man, he was despised. We were not allowed in the Marines or the Navy, and when we were able to serve in the Navy, we were servants such as cooks and cleaners. He proudly sits in that uniform, and he demands attention. The artist did an extraordinary job rendering this painting. The entire image is beautiful! I am a veteran, and I know the pride and dignity that he is feeling.

L’Merchie Frazier: It reminds me of the writing of Frederick Douglass when he said that he did not trust the artist, that the photograph became the document because it was the real image. With this painting, we may not even really know what his true expression was. I am hoping that the artist’s rendering is genuine, because there is a complexity to it. It reminds me of my uncles who served in that war and who wore this uniform, and some of the stories they told me were not glorious stories, you know.