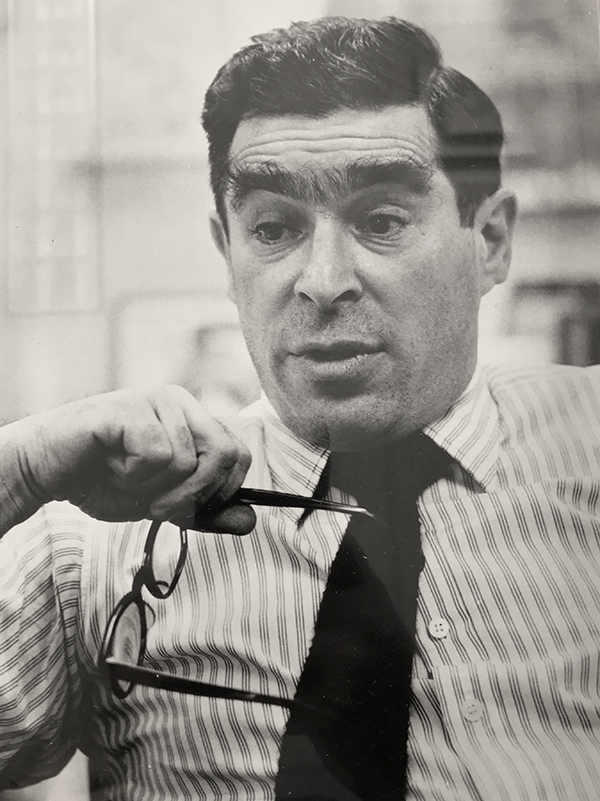

Cuno further noted that Kramarsky “likes to change people’s lives. He would never say that, but it’s true. He did this through his work in government. And he does it still with his drawings: changing the lives of artists, students, and others who come to discover the honesty of drawings and the sincerity of Wynn’s commitment to them (to works of art as well as to people).”[3]

Kramarsky’s donations to Harvard ensure that future generations of students, faculty, and the public will have access to the works he enjoyed and will no doubt inspire the kinds of conversations he relished. He gave masterpieces such as Jasper Johns’s Wilderness I (1963–70), which he presented in recognition of the success of the Drawing is another kind of language exhibition, as well as works by less-familiar artists he admired. For anyone interested in drawing as a medium, Kramarsky’s donated works, including those by William Anastasi, Suzan Frecon, Sol LeWitt, Karin Sander, Richard Serra, Robert Smithson, and many other artists, continue to offer inspiration and encouragement.

Friends and collaborators of Wynn Kramarsky offered their memories of this remarkable man:

Pamela Lee, Carnegie Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art, Yale University

As a graduate student, I always appreciated the foundational importance of drawing in the history of art, but I neither studied nor wrote about drawing in any systematic way. Wynn Kramarsky gave me and Christine Mehring the opportunity to do just that when Drawing is another kind of language was planned for the Harvard Art Museums in the late 1990s and we were recruited to write for the catalogue. Wynn’s extraordinary collection included all my favorite artists from the 1960s and 1970s (Eva Hesse, Sol Lewitt, and Robert Smithson, to name just a few) but many other names I did not know but came to know—and love. Because of this encounter with contemporary drawing, I’ve gone on to write and lecture about the topic with some regularity ever since. An exceptional collector, Wynn was an exceptional human being: incredibly kind, humble, and always interested in learning—and giving—more.

Christine Mehring, Professor and Chair, Department of Art History, University of Chicago

Working on that [Drawing is another kind of language] catalogue as a fourth-year graduate student, and working so closely with Wynn, launched and shaped my career as an art historian in so many ways. Not only did it become my first serious art historical publication that helped me garner my first teaching job at Yale (where I got to work more with Wynn!), Wynn’s eye, and curiosity about mine, instilled confidence in my own, seemingly old-fashioned, “connoisseurial” passions. His vast knowledge opened up for me the many different functions of drawings for artists, which became crucial for my dissertation and for so much art historical research since. Sitting in the 560 Broadway loft [in New York] every day for a summer, writing with my friend Pam Lee across the table and an original drawing at my side, taught me close looking and disciplined writing, which were always rewarded with Wynn’s humor and brownies from Olive’s. As faculty and chair of art history at the University of Chicago, I have tried to give back just these experiences—organizing visits to local private collections and starting a large-scale collaboration with the Art Institute of Chicago to enhance object-driven training for our doctoral students, which I’d conceived with Martha Tedeschi before she left for the Harvard Art Museums!

William Robinson, George and Maida Abrams Curator of Drawings, Emeritus, Harvard Art Museums

Wynn first got involved with the Harvard Art Museums through his friendship with former director Jim Cuno, and for more than a decade afterward the Drawing Department benefited from his remarkable generosity and peerless knowledge of contemporary drawings. With the shows at his 560 Broadway gallery [in New York] and his support of museums and other exhibition spaces, he selflessly cared to foster the artists he admired. Some were established figures, such as Richard Serra and Sol LeWitt, and many were women; most were young and emerging—or not yet emerged—when he visited their studios, bought their work, encouraged curators and other collectors to acquire it, and, eventually, placed it in museums. Wynn gave Harvard important drawings by Serra, LeWitt, and Jasper Johns, but it was above all his advice and example that influenced the direction of the collection.

Elise Kaufman, Artist and Collections Administrator for Wynn Kramarsky, 1992–94

He was one of the most remarkable individuals I have ever known. Generous. Astute. Funny as heck and an autodidact with an incisive intellect, the breadth of which was astonishing. He was able to toggle between the widest range of constituencies: artists (at wide ranges of careers: from the emerging young ones—me—to those far more established), curators/scholars, politicians, as well as the guy who retrieved his car from the parking garage. And he made me (and many others, I suspect) feel like I was the only artist in the world and that what I had to say and share was of value. He was my validator-in-chief and I cannot emphasize strongly enough how his attention to me and to my work supported me.

Amy Eshoo, Assistant to Wynn Kramarsky, 1998–2003

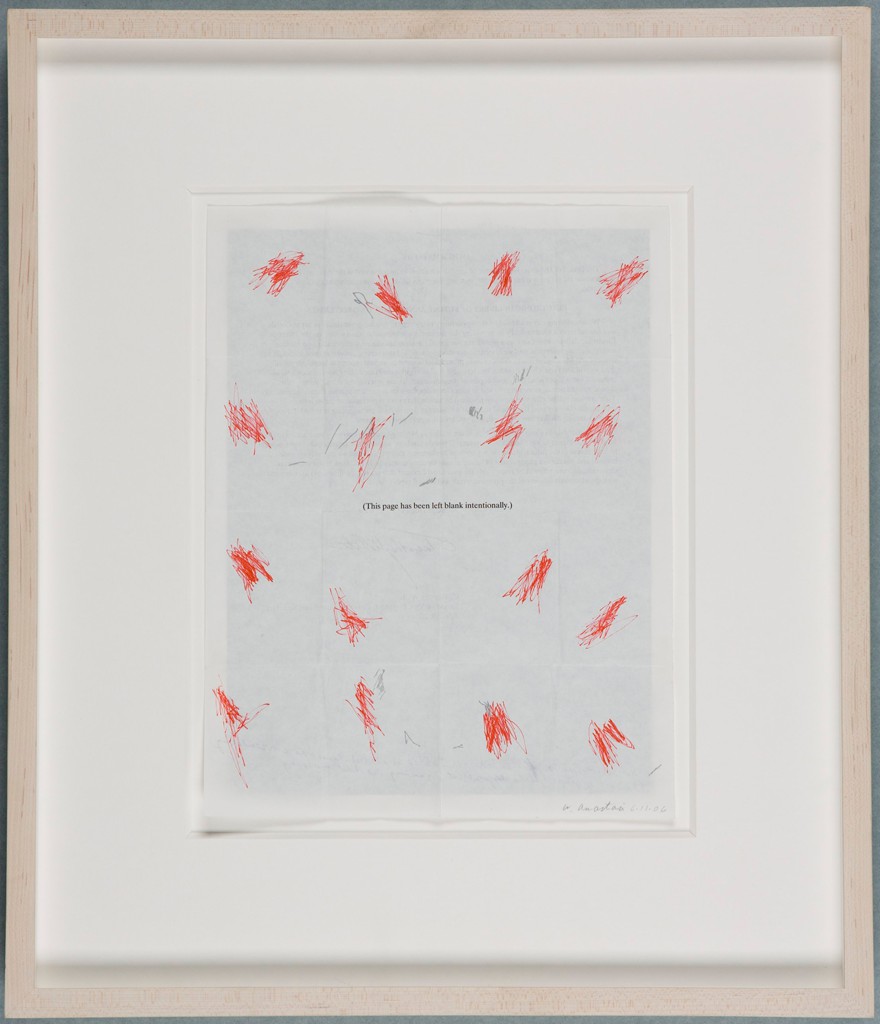

His intent was to support American artists working in an abstract language, which during the main years of his collecting had fallen out of “fashion” in the contemporary art world. He steadfastly focused on works on paper, no matter what form that took; he called marks on a flat surface a drawing. To him it really was a language. His giving to art institutions across the country was an effort on his part to share his love for this language and form with those who might not otherwise ever be introduced to it. He specifically would choose learning institutions: museums attached to universities or colleges, places where there was the chance that a viewer, a student, could spend extended time, perhaps handling time, with a work of art. He was a most unpretentious and generous teacher who used his sense of humor to lead the way. He would never tell anyone what to see but would share what intrigued him. Wynn’s passion for the drawings and the artists was infectious. His reverence for the works of art was included in their being part of his world as many of the artists intended—not to be isolated and worshiped but to be incorporated and experienced in everyday life.

Joachim Homann is the Maida and George Abrams Curator of Drawings at the Harvard Art Museums.

1. Pamela Lee and Christine Mehring, Drawing is another kind of language: Recent American Drawings from a New York Private Collection (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Art Museums; Stuttgart: Daco-Verlag Günter Bläse, 1997).

2. Amy Eshoo, ed., 560 Broadway: A New York Drawing Collection at Work, 1991–2006 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2008), 102–10.

3. Ibid., 101.