Five monumental Chinese paintings, which draw on a medieval Buddhist text known as the Scripture on the Ten Kings, have just returned to the Harvard Art Museums after spending three years undergoing specialized conservation treatment in Japan.

Reigning over a Hellish Bureaucracy

Based on rituals described in the text, Ten Kings of Hell paintings portray the dead facing the judgment of a different king of the underworld every seventh day after their passing. Like the circles of torment described in Dante’s Inferno, the paintings illustrate multiple hells and visceral torture scenes. The underworld, which functions as a kind of hellish bureaucracy, is driven by magistrates who mete out the punishment appropriate to each sinner who appears before them, assisted by clerks and other functionaries.

The five Ten Kings of Hell paintings in the Harvard Art Museums collections are in the hanging scroll format; each is nearly eight feet tall and dates to the Ming dynasty (15th–16th century). Four of the five are now on view in gallery 2740.

History of the Ten Kings of Hell at Harvard

The Harvard paintings were originally part of a set of ten (the whereabouts of the remaining five are unknown). Remarkably, these examples entered the museums’ collections over a period of almost 40 years from different donors. Three—the scroll above and the two below—were given to the museums in 1966 by Clifford Kaye.

In the summer of 1979, Professors Donald Rabiner and Claudia Brown of Arizona State University discovered that they owned two paintings from the same set, one of which they generously donated to Harvard that same year. In 2002, Professor Brown and her daughter, Emily, gifted the last painting from the same set to Harvard (pictured below).

Conservation of the Scrolls

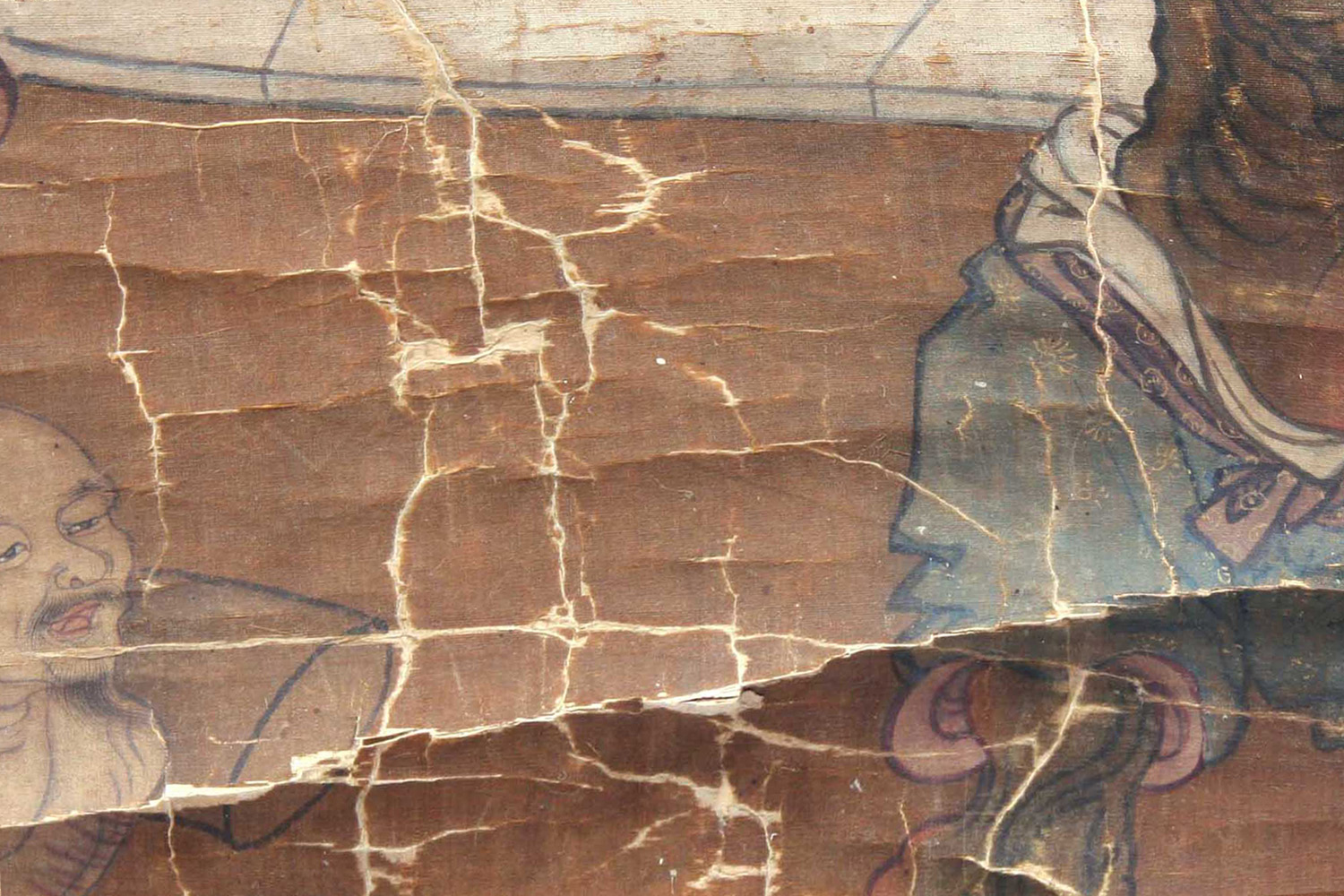

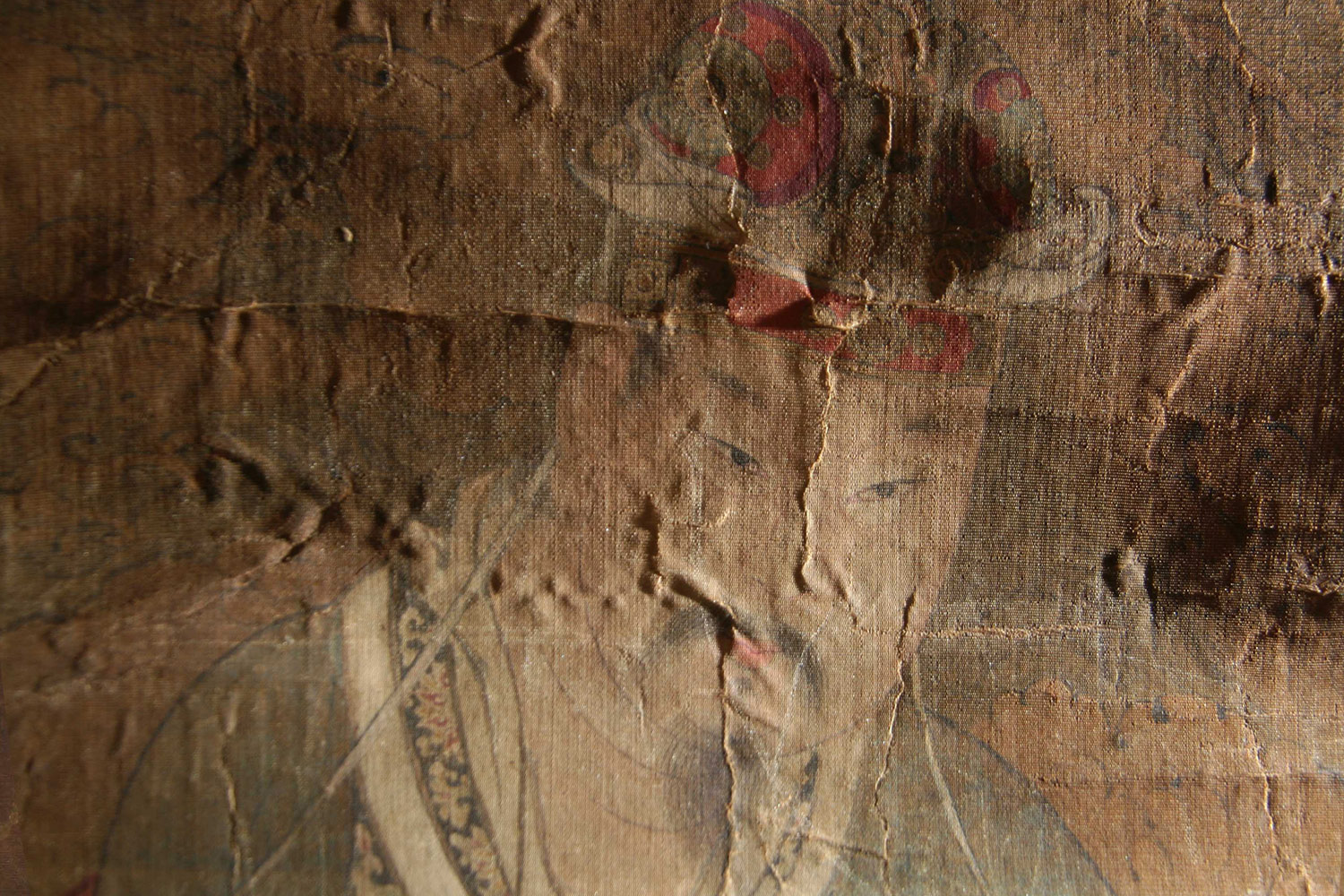

When staff from the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies examined the paintings prior to the museums’ reopening in 2014, it was clear that all five objects were in serious need of conservation. Some of the paint was flaked or cracking, and there was a good deal of creasing and staining. In addition, a few of the paintings had been repaired with tape, which caused their silk mountings to deteriorate and delaminate in areas.

The paintings themselves are mounted onto multilayered silk and paper structures that allow them to be rolled for storage. Over time, these structures break down and are usually replaced every hundred years or so. Each of our five paintings was overdue for this kind of maintenance. Moreover, one of the paintings had been cut out of its hanging scroll mounting and then framed, which meant that it would take some work to return it to its original format. Because the paintings are meant to be experienced as a group, all five needed to be remounted in the same way, as they originally would have been.

The Straus Center typically performs conservation treatment of objects in the museums’ collections, but the conservation of Asian paintings in hanging scroll and folding screen formats is a specialized type of conservation work that the museums cannot undertake. Fortunately, the museums have an ongoing relationship with the Japan-based conservation studio Handa Kyuseido. A member of the Association for Conservation of National Treasures, this studio is authorized to treat works of the highest caliber. The studio’s conservation of our Ten Kings of Hell paintings was made possible by the generosity of the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation and the Ernest B. and Helen Pratt Dane Fund for Oriental Art.

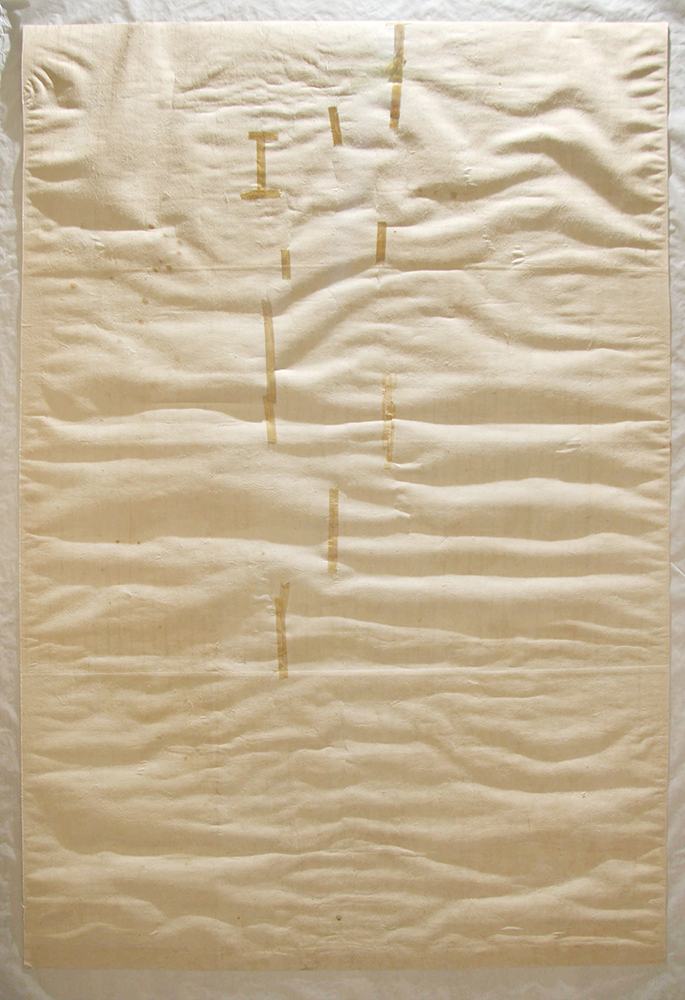

The treatment of Asian paintings, particularly hanging scroll format works, is a highly involved process. The paint layers are secured with dilute animal glue, delicate areas are faced with a thin paper to protect them until later in the treatment process, and the painting is turned facedown on a long, low table. The many backing layers are removed one by one (in this case, there were four), through wetting and peeling.

The removal of the old backings of our Ten Kings of Hell paintings offered some surprises. A number of the layers were comprised of Korean papers, indicating that the scrolls, made in China, had probably been remounted at some point in Korea. The treatment also revealed clear evidence of the urazaishiki technique, which entails painting on the back side of the silk ground of the painting to enhance the depth of the pigments and to add nuance to the composition.

The removal of the old linings continued until, finally, only the original silk support remained. After losses and holes were filled from the back with new silk that was dyed and carefully aged to blend with the original, the paintings were remounted and backed with several layers of backing papers. The Handa studio used Japanese papers for the first five linings, finishing with a final lining of handmade Chinese paper—a fitting choice for these Ming dynasty paintings.

Ten Kings of Hell Iconography

Despite the painstaking conservation of these delicate scrolls, which took three years to complete, this was but a brief chapter in the life of these centuries-old objects, which are part of an even older pictorial tradition.

Illustrations of the Ten Kings of Hell were found within the ninth-century Scripture on the Ten Kings, stored in the Dunhuang cave complex in China. The text presents the afterlife as a three-year journey undertaken by the deceased, passing through courts administered by ten different Kings of Hell.

Seven days after death, the dead appear as prisoners in front of the first king. Acting as magistrate in this bureaucratic setting, the king listens to the prisoner’s plea before meting out the appropriate punishment for sins committed during life. The severity of the ensuing torture depends on the transgressions and is counterbalanced by offerings made on behalf of the dead by the living relatives.

Every seven days, the deceased passes through the court of a different king until, on the 49th day, he or she faces the seventh king. Next, the dead appear before the eighth king after 100 days, the ninth king after 13 months, and the tenth king after 3 years.

In contrast to the orderly layout of the king’s court in the upper half of each painting, the lower half is full of chaos, replete with scenes of punishment and torture. These images drew not only on the Scripture on the Ten Kings, but also on numerous non-canonical writings and depictions of hell and the underworld. Descriptions of prisoners being boiled in a flaming cauldron, ground in a mill, or forced to climb mountains of blades had a long history in early Chinese literature about the underworld.

The Harvard paintings were likely produced in an atelier in the eastern Chinese port city of Ningbo, where workshops created multiple sets of Buddhist paintings for local temples as well as for export. Japanese temples acquired these paintings for ritual use and, in many cases, continue to treasure them today. A complete exemplary set, which has been designated an Important Cultural Property, is now in the collection of the Nara National Museum.

Though the five Harvard paintings represent just one half of the original set, they share a distinctive history that spans the globe. Made in China, possibly used in a Korean temple, conserved in Japan, and now studied and exhibited in the United States, these paintings tell a remarkably global story, just one example of the type of international collaboration that the Harvard Art Museums are undertaking.

Wai Yee Chiong is the Cunningham Curatorial Fellow in Japanese Art, and Penley Knipe is the Philip and Lynn Straus Senior Conservator of Works on Paper and head of the paper lab in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, at the Harvard Art Museums.