What happens when a recently conserved painting is ready for display in the galleries but its frame is all wrong? This is the story of how a curator and frame conservator teamed up to create a historically accurate reproduction of an unusual 19th-century frame.

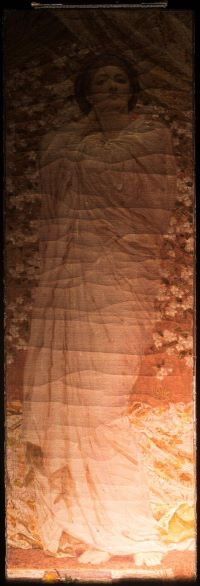

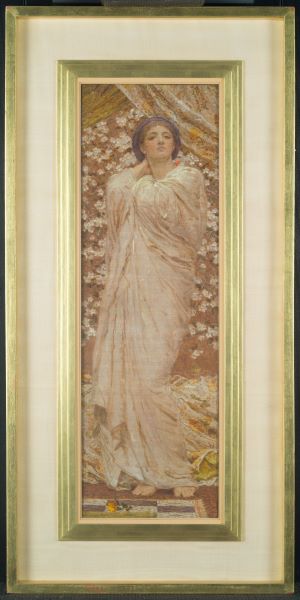

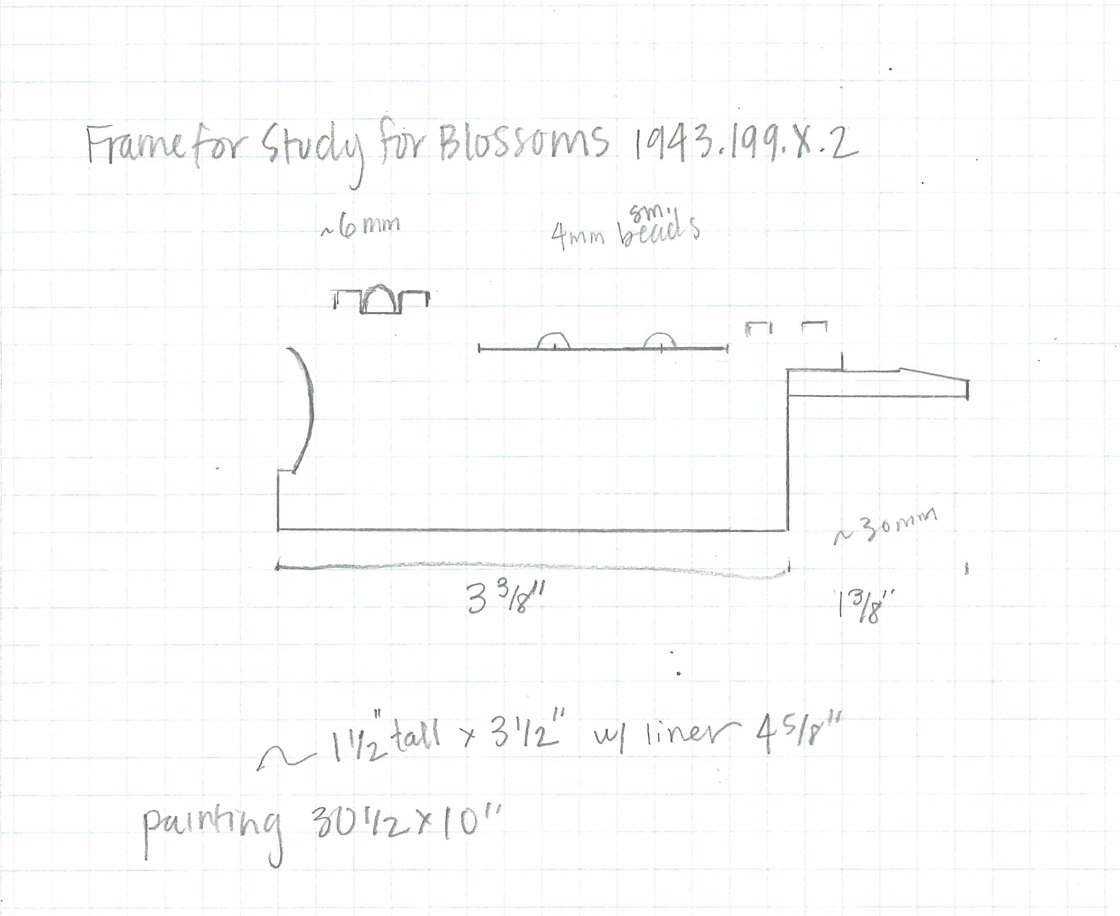

In the summer of 2019, Miriam Stewart, curator of the collection in the Division of European and American Art, considered organizing a display of paintings and drawings by 19th-century British artist Albert Moore. Examining the museums’ four works by Moore, Stewart was struck by the condition of the painting Study for “Blossoms.” With a dramatic tenting crack pattern covering its surface, the painting appeared to need extensive conservation treatment. Stewart requested the work be brought to the paintings lab in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Study for examination by paintings conservator Kate Smith. This transfer of the work from storage to the lab set in motion a dynamic multipronged, collaborative project that spanned three years, involving six Harvard Art Museums colleagues and the expertise of a local frame-maker and five paintings conservators, conservation scientists, and frame conservators in the United Kingdom.