“There’s something about having the chance to borrow and hang an original print in your room that lets you really connect with it,” said Eloise Lynton, a history of art and architecture concentrator who is graduating this December. “It becomes part of your everyday visual experience in a way that has an impact on your overall time at Harvard.”

Prints to Rent—and Relish

Lynton should know. Not only did she and her roommates borrow a print to hang in their dorm during the 2016–17 academic year (Louise Bourgeois’s Eight in Bed [2000]), she just spent her summer researching many of the over 300 objects in the museums’ Student Print Rental Collection.

As part of an internship supervised by Elizabeth Rudy, the Carl A. Weyerhaeuser Associate Curator of Prints, and curricular registrar Jessica Diedalis (who oversees the Student Print Rental Program), Lynton delved into the details behind the prints in the rental program. The goal of her internship was to research new information about the works for the benefit of future student borrowers.

“In previous years, students have come to the museums to try to find out more about the prints they’ve borrowed, and now we want to be able to provide them with information when they pick up their print,” Lynton said.

The program, formally established in 1972, allows undergraduate and graduate students to borrow framed, original prints for the academic year. Works to rent are part of a collection designated specifically for the student program; there are a number of well-known artists represented—Andy Warhol, Claes Oldenburg, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso among them—but many lesser-known standouts as well. The aim of the program is to introduce and expose Harvard students to original art in a unique way: by living with it.

This year’s print rental period occurred on August 28 and 29, and was a swift success. By the middle of the second day, all 259 prints on offer had been rented. (The fee for rental during the 2017–18 academic year is $30.)

“The Student Print Rental Program is a wonderful Harvard tradition,” Rudy said. “Through her internship, Eloise has helped us improve and enrich the program. Her careful research and unbridled enthusiasm for prints have added so much to our existing resources about this special collection, and we are pleased that we can share this material with our student borrowers this year.”

In some cases, Lynton’s research involved filling in the blanks about works that were donated to the collection without much context—adding or correcting artists’ names, dates, and other critical details. In other instances, she was uncovering larger stories behind certain works.

“Overall, this was one of the best experiences I’ve had at Harvard,” Lynton said. “I learned a lot from working with the collection and thinking about how other students engage with it.”

Here, Lynton shares some of what she learned about a few works in the collection.

Bruce Conner, Lincoln Center, 1965

Conner created this print in 1965 for the New York Film Festival. Each year, the festival commissions a contemporary artist to design a poster for the show.

Rather than making a traditional poster for his commission, Conner produced TEN SECOND FILM, a short work that he wanted to play as a “leader” before the featured films. Conner’s film was made up of 10 strips of 24-frame-long footage, which played at the average speed of 24 frames per second—making his film last a total of 10 seconds. TEN SECOND FILM thus visually riffed on the material from which the film was constructed to play with ideas of time and materiality.

Ultimately, Conner’s film was rejected by the festival because it was “too fast”; however, the festival agreed to use his first frame as the official poster that year.

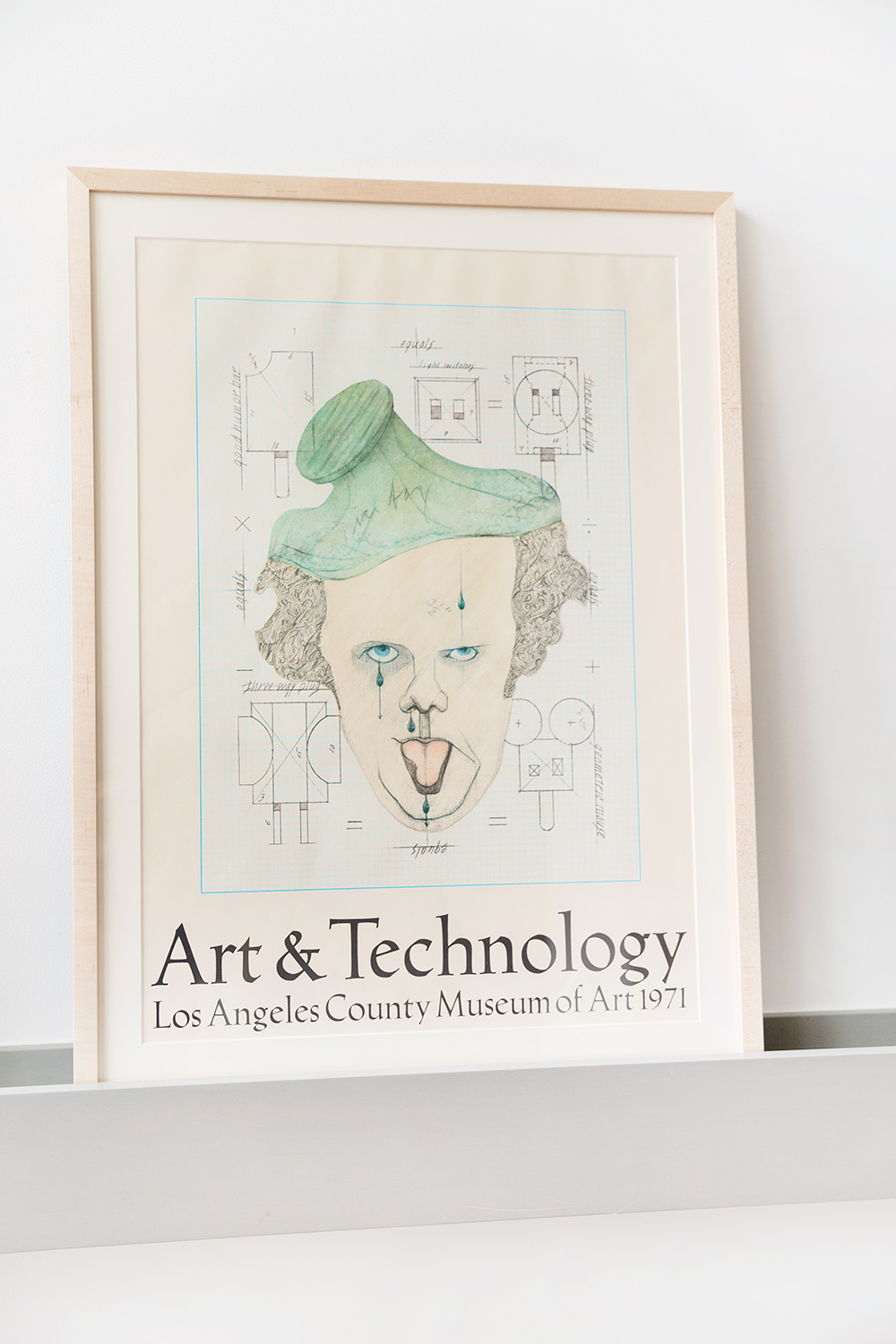

Claes Oldenburg, Symbolic Self-Portrait with Equals (poster for Art & Technology), 1971

In the late 1960s, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) began its Art & Technology initiative, a program that paired contemporary artists with technologically focused institutions in order to create new works of art. (The program continues in a similar form to this day.) In 1968, Claes Oldenburg collaborated with Disney animators to create a large kinetic sculpture for the 1970 World Expo in Osaka, Japan.

Oldenburg brainstormed numerous ideas. Some early thoughts included creating a “giant toothpaste tube . . . which rises and falls,” a “colossal rising and falling screw” that releases oil, and “a large undulating green jello [sic] mold.” Eventually, he settled on creating an oversized “ice bag,” which would slowly deflate as if the ice inside were melting.

About halfway through the project, Disney backed out. Oldenburg instead partnered with a company called Gemini G.E.L. and Kroft Enterprises. Due to time constraints, the sculpture had to be created in three months. The finished product, made of vinyl and powered by six fans inside its base, was 18 feet wide and 16 feet tall.

This print was created as a promotional poster for a group exhibition at LACMA in May 1971, where Oldenburg showed his sculpture. The ice bag is visible on the head of the figure in the poster.

Today, one of the three surviving sculptures based on Oldenburg’s model resides at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Walter Simonson, Samurai, c. 1970

This poster was created by Walter Simonson when he was a student at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). For his senior thesis, Simonson created a 50-page black and white comic book series titled Star Slammers. Later, in 1983, the book was published by Marvel. It’s possible that this early print is a color rendition of one of the many characters from Simonson’s series.

After Simonson graduated from RISD in 1972, he became a comic book illustrator. He’s perhaps best known for his work on Marvel Comic’s Thor in the 1980s.

Joan Miró, Composition (after Harkness Common Mural), 1951

Miró originally designed this mural for the west wall of Harvard’s Harkness Graduate Center cafeteria. The Harkness building, designed by Walter Gropius, was decorated with artwork by other prominent 20th-century artists as well, including Josef Albers, Jean Arp, and Herbert Bayer.

Miró’s original design (of which the museums have multiple prints in the Student Print Rental Collection) is thought to represent a bullfight. A large bull with horns stands in the middle. To the left, a fighter with banderillas faces the bull. The figure next to him may be the back of a picador’s horse. At right, the matador stands at the ready with his flag in hand.

The mural was controversial among students at the time, who criticized its “weirdly shaped forms,” according to the Harvard Crimson.

In 1960, the mural suffered damage due to a combination of humidity and food stains. Miró replaced it with a more durable ceramic tile version and donated the original mural to the Museum of Modern Art, in New York, where it now resides.