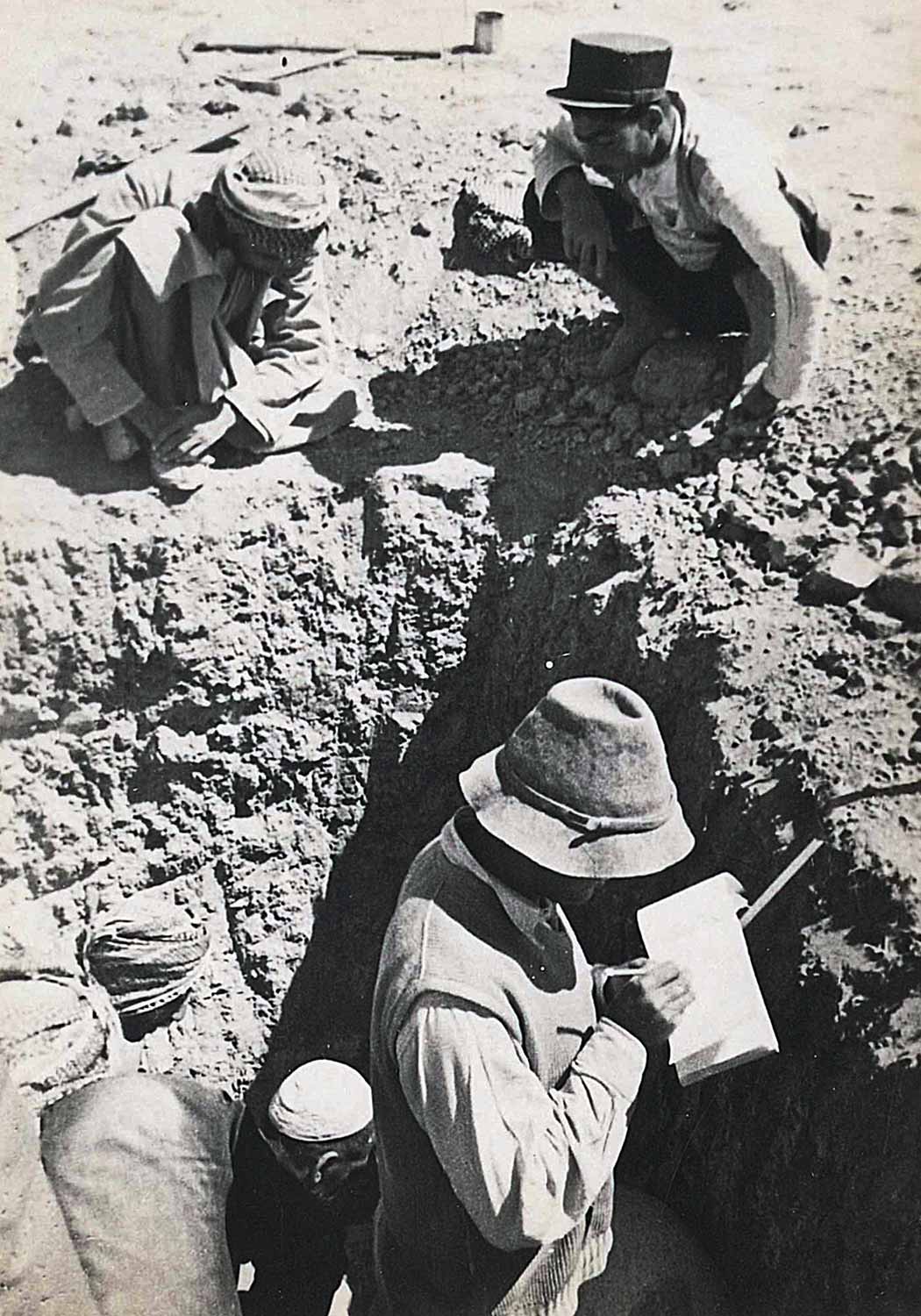

Archaeological excavations have always been exhausting yet exhilarating work for nearly everyone involved—including the excavation photographer.

Persepolis from a Photographer’s Perspective

German photographer Hans-Wichart von Busse (1903–1962) held that role in 1933 and 1934 during an archaeological expedition to Persepolis, one of the capital cities of the Achaemenid Persian Empire (c. 550–330 BCE) in Iran, near the modern city of Shiraz. As part of a team led by archaeologist Ernst Herzfeld for the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, von Busse took carefully staged images of the site’s ruins, as well as candid snapshots of the people involved. He saved copies of what he considered his best works, which later came to be part of his archives.

Now, dozens of von Busse’s photographs from the Persepolis excavation will be shown at the Harvard Art Museums over the summer and fall, and again in Summer 2018. On loan from the private collection of Azita Bina and Elmar W. Seibel, the images form the core of three themed installations in the gallery of Near Eastern Art (3440). They will complement both the Persepolis relief fragments on view nearby and the upcoming special exhibitions Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran (August 26, 2017–January 7, 2018) and Animal-Shaped Vessels from the Ancient World: Feasting with Gods, Heroes, and Kings (September 7, 2018–January 6, 2019).

Mira Xenia Schwerda, a Ph.D. candidate in Middle Eastern Studies and the History of Art and Architecture at Harvard, organized the installations as part of her internship with Susanne Ebbinghaus, Amy Brauer, and Mary McWilliams, curators in the Division of Asian and Mediterranean Art.

“These photographs give us new information about the site and its structures,” Schwerda said. “They also help us understand not only daily life but even what special events were held there.”

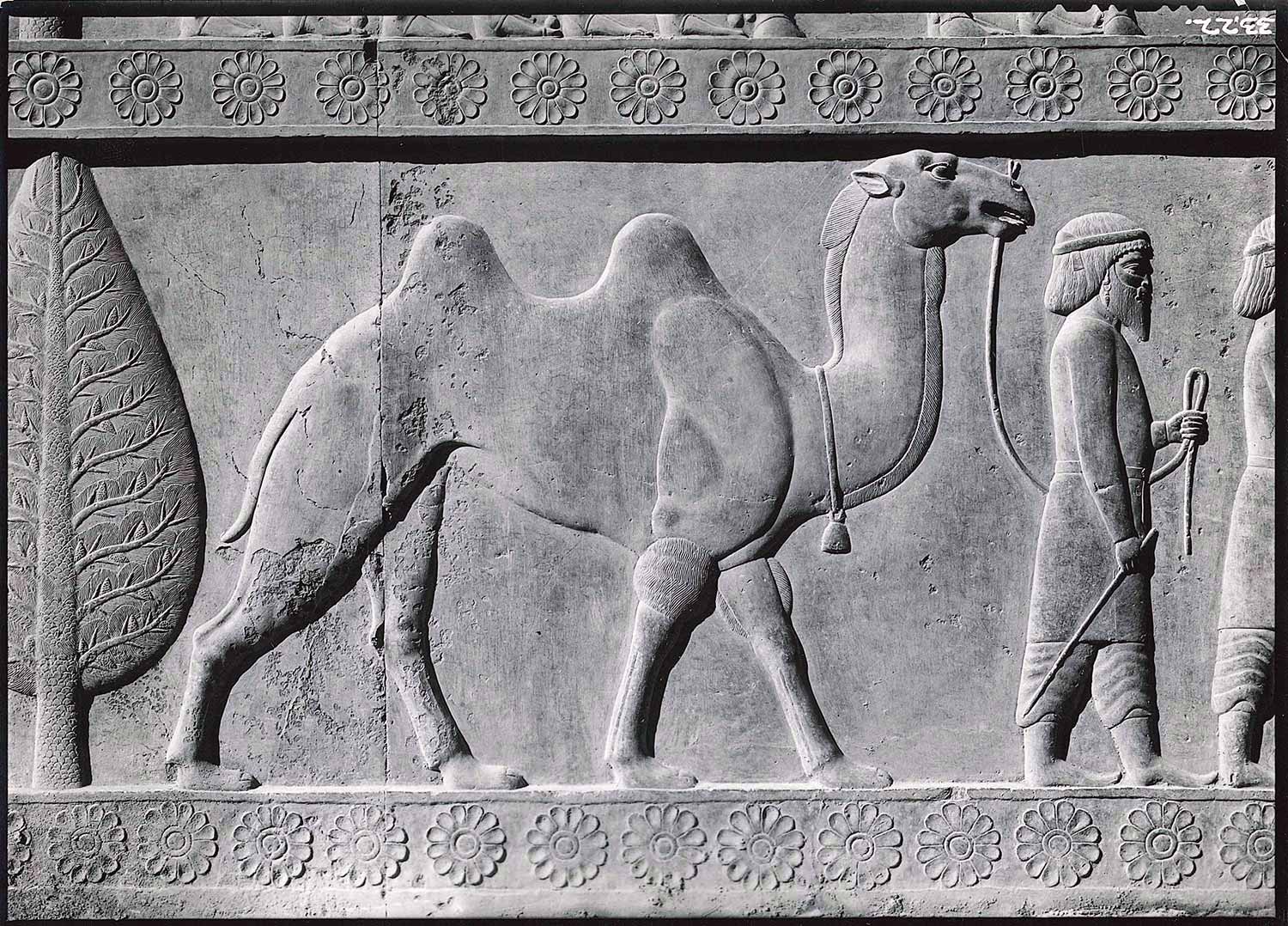

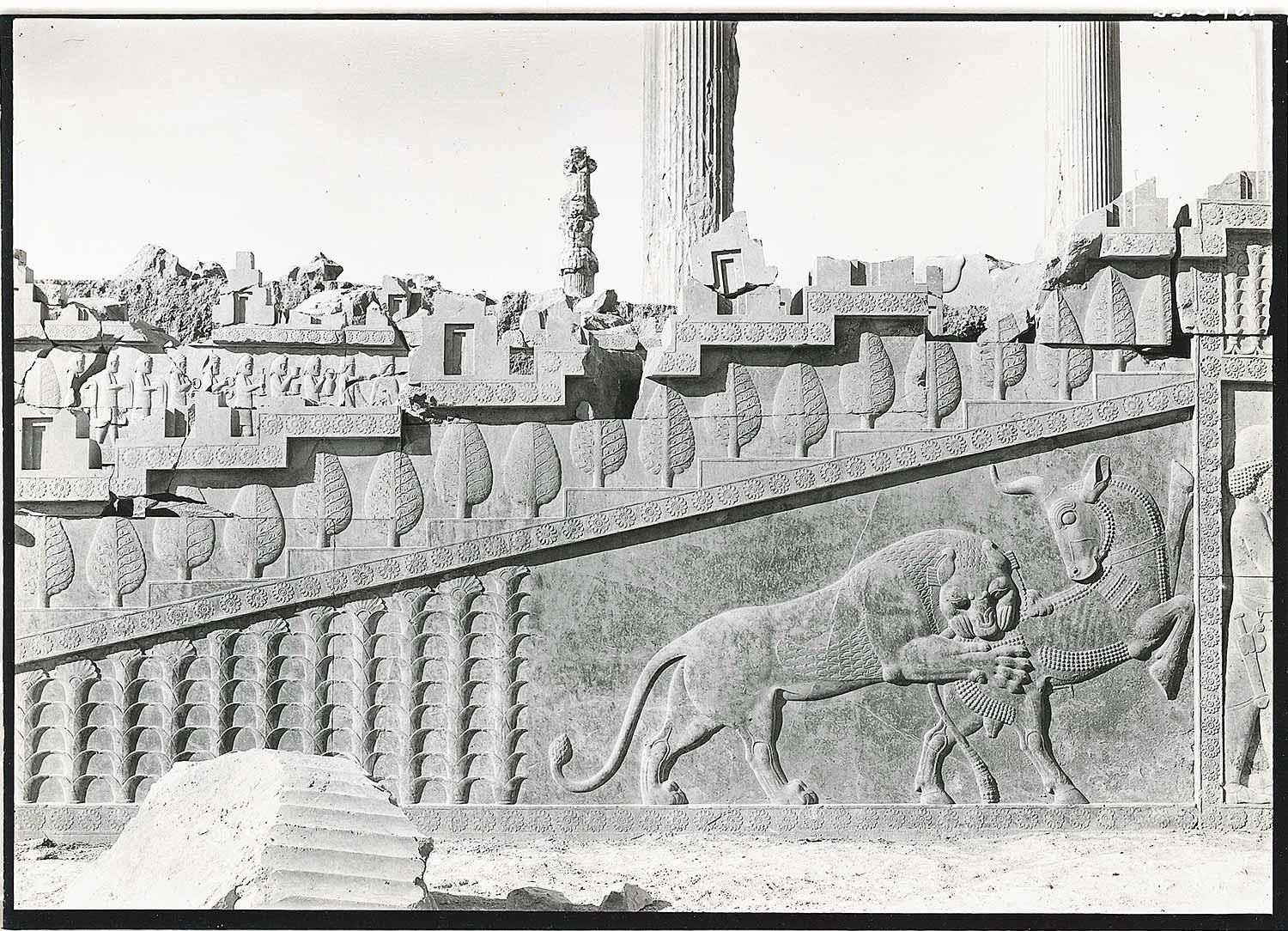

The aesthetic quality of the photographs is impressive as well. Ebbinghaus said that the angles von Busse chose caused her to properly appreciate the prominence of plant motifs in the sculptural decoration at Persepolis.

Momentous Event

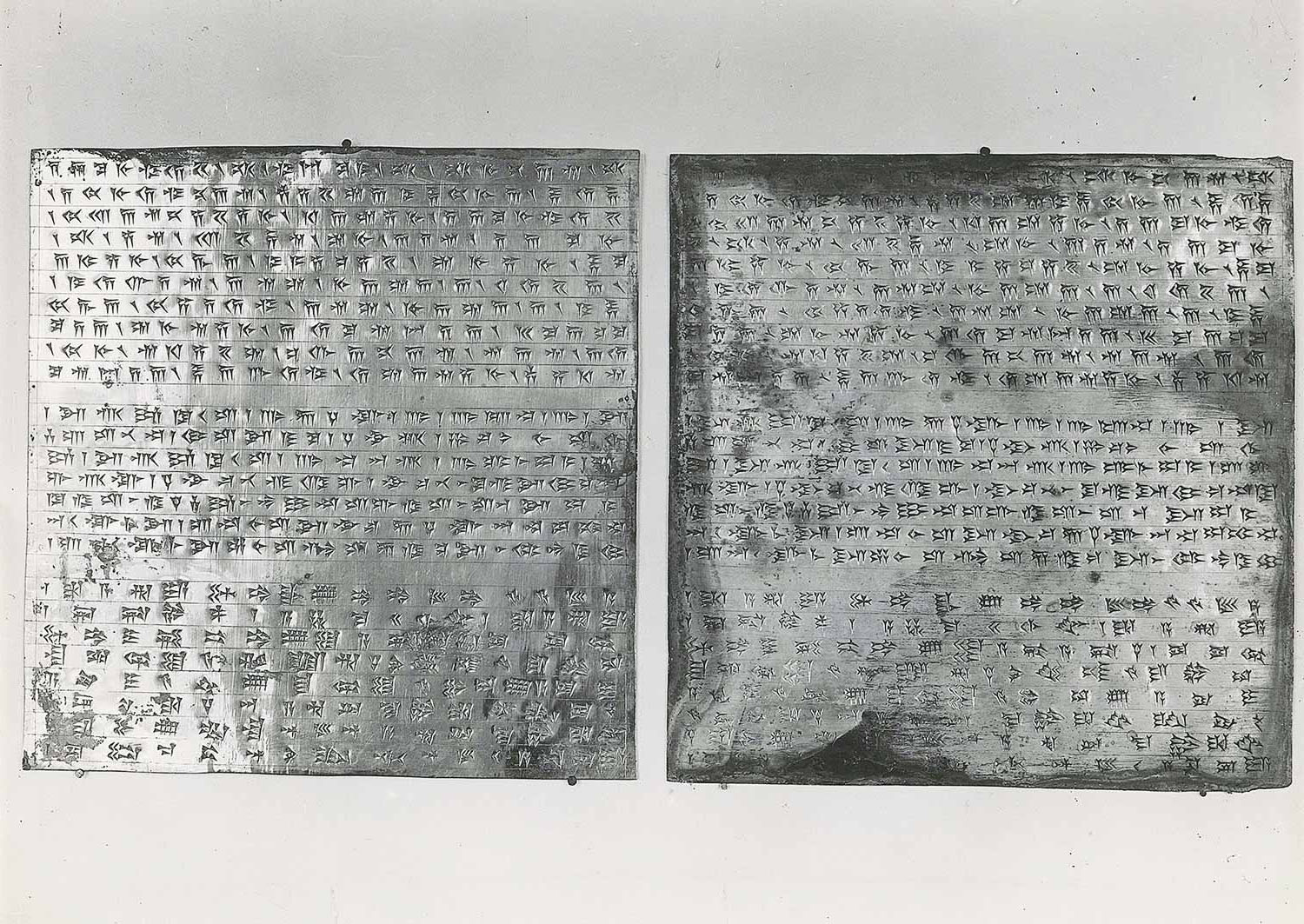

One of the occasions captured in von Busse’s photographs was the discovery of two tablets—one gold and one silver—under the walls of the Apadana, or audience hall, a massive building consisting of three porticoes and an enormous square hall with six rows of six columns. Nestled inside a carved limestone box, the tablets were an especially exciting find because they bear Old Persian cuneiform inscriptions of the Achaemenid king Darius (r. 522–486 BCE), who founded Persepolis. Von Busse captured this discovery, which he made with his friend Friedrich Krefter (the site’s architect), with both formal photographs and smaller, candid snapshots. Examples of these images will be displayed in the first installation, on view between June and September 2017.

Across 18 snapshots, von Busse had written a poem; the back of each photograph contains one verse. Schwerda (a native German speaker) took on the task of translating the entire poem, discovering that it told a fanciful tale in Berlin dialect about the tablets’ discovery. Von Busse had created an album of the snapshots and gave it to Krefter, who was pictured making the discovery. Von Busse saved a copy for himself, which was later added to his archives.

“The story of an excavation with obstacles, in 18 moving pictures and even worse prose,” the poem begins, according to Schwerda’s translation. It goes on to describe the digging process, the anticipation of discovery, and ultimately the revelation that the tablets were indeed where they had been expected. “At long last, at this very place, ‘the silent delight,’” the poem concludes.

Ties to Exhibitions

The second installation that Schwerda curated, which will be on view in October, will display shots of the excavation itself and the excavation house. The team had reconstructed one of the ancient buildings according to their understanding of its original appearance, and they lived and worked in it during the expedition. Schwerda pointed out one photograph in particular that will be of interest: a snapshot of the living room, holding 19th-century Qajar art on the walls. Astute visitors will notice a connection to the Technologies of the Image exhibition, which features Qajar paintings, prints, and photographs.

In fact, there’s another correlation between the exhibition and von Busse’s photographs: both include images of Achaemenid sculptural reliefs from Persepolis. “The Qajars were really interested in pre-Islamic dynasties, and in linking themselves to those dynasties,” said Schwerda, who also worked on the Technologies of the Image exhibition and contributed to its catalogue.

The third installation, to be shown in later 2018, will highlight Achaemenid representations of animals and mythical creatures at Persepolis, as captured by von Busse. This is another timely focus, as the museums will simultaneously be presenting the special exhibition Animal-Shaped Vessels from the Ancient World, which will feature several Achaemenid works. One group of photographs shows the reconstruction of a large bull sculpture that once sat atop a column. Another group includes photographs of a stone fragment in the shape of a lion’s head, perhaps the foot of a throne, as well as snapshots depicting von Busse taking those very photographs.

Insight into Two Careers

Herzfeld’s work as a Near Eastern scholar has a lasting legacy, and these images offer an intimate and personal glimpse into a key stage of his life and career. The year 1934 was Herzfeld’s last at Persepolis. As a German archaeologist who was also Jewish, he left the excavation and eventually joined the faculty of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey; he never returned to Persepolis.

Von Busse, who also left the site in 1934, had only one set of published Persepolis photographs to his name—panoramic photographs of the striking eastern staircase facade of the Apadana, which were printed in the Illustrated London News. He continued taking photographs as part of future jobs, but “his work was never really appreciated,” Schwerda said. With the Harvard Art Museums’ installations of his photographs, a short but important period from von Busse’s life is finally getting attention.