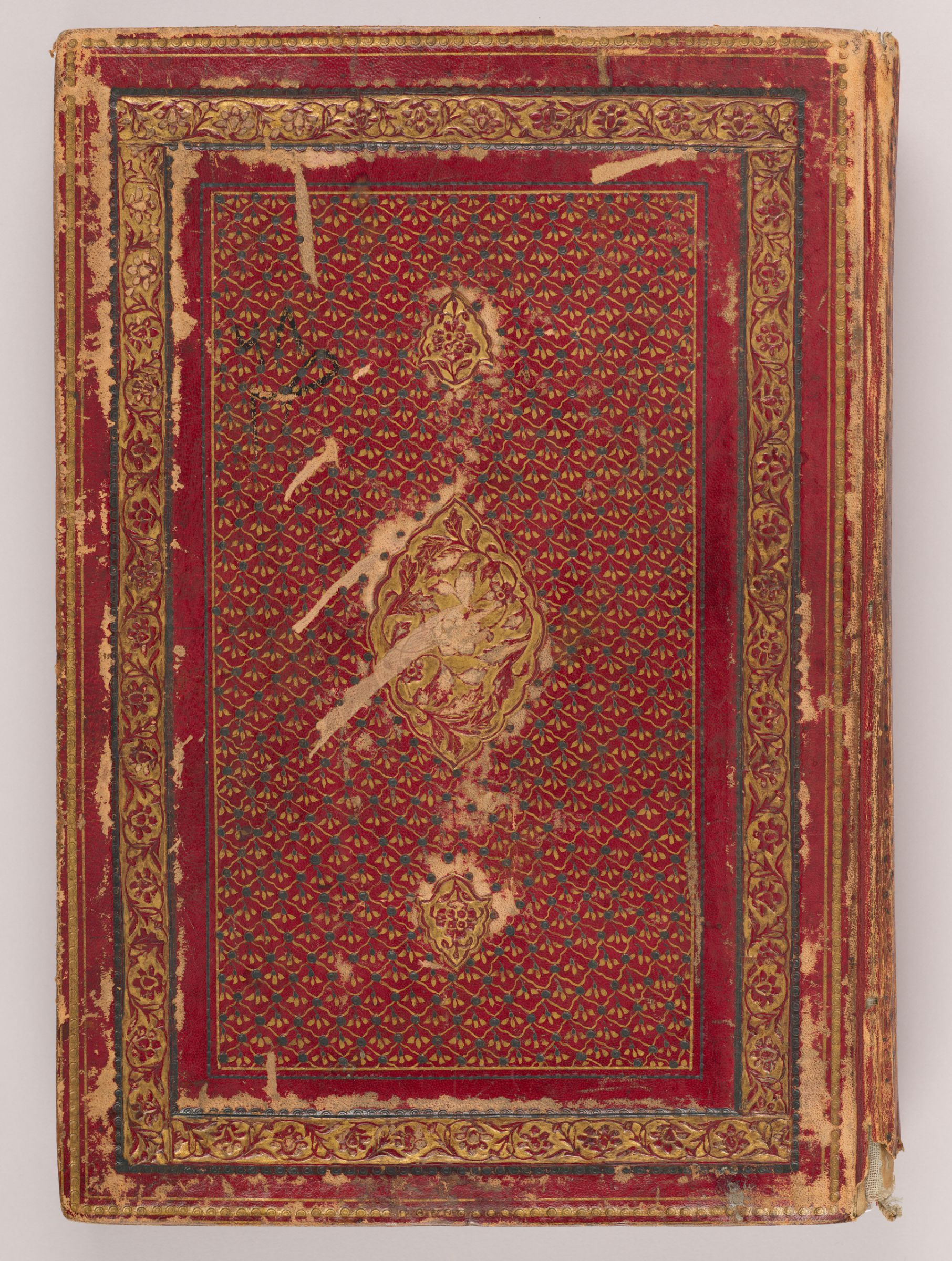

Nearly 10 years ago, Mary McWilliams and David Roxburgh sat down together to look at a unique album from 19th-century Iran. Filled with preparatory sketches, drawing templates, and fully developed compositions by a range of artists, the album had until then been little studied since Harvard acquired it in 1960.

Mobile Images from 19th-Century Iran

“I was incredibly excited when I first saw the album,” said David Roxburgh, the Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Professor of Islamic Art History and chair of the Department of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard. “I appreciated its rarity, but also the premise that its publication could encourage others to work on related materials. I was eager to do a serious study of this album.”

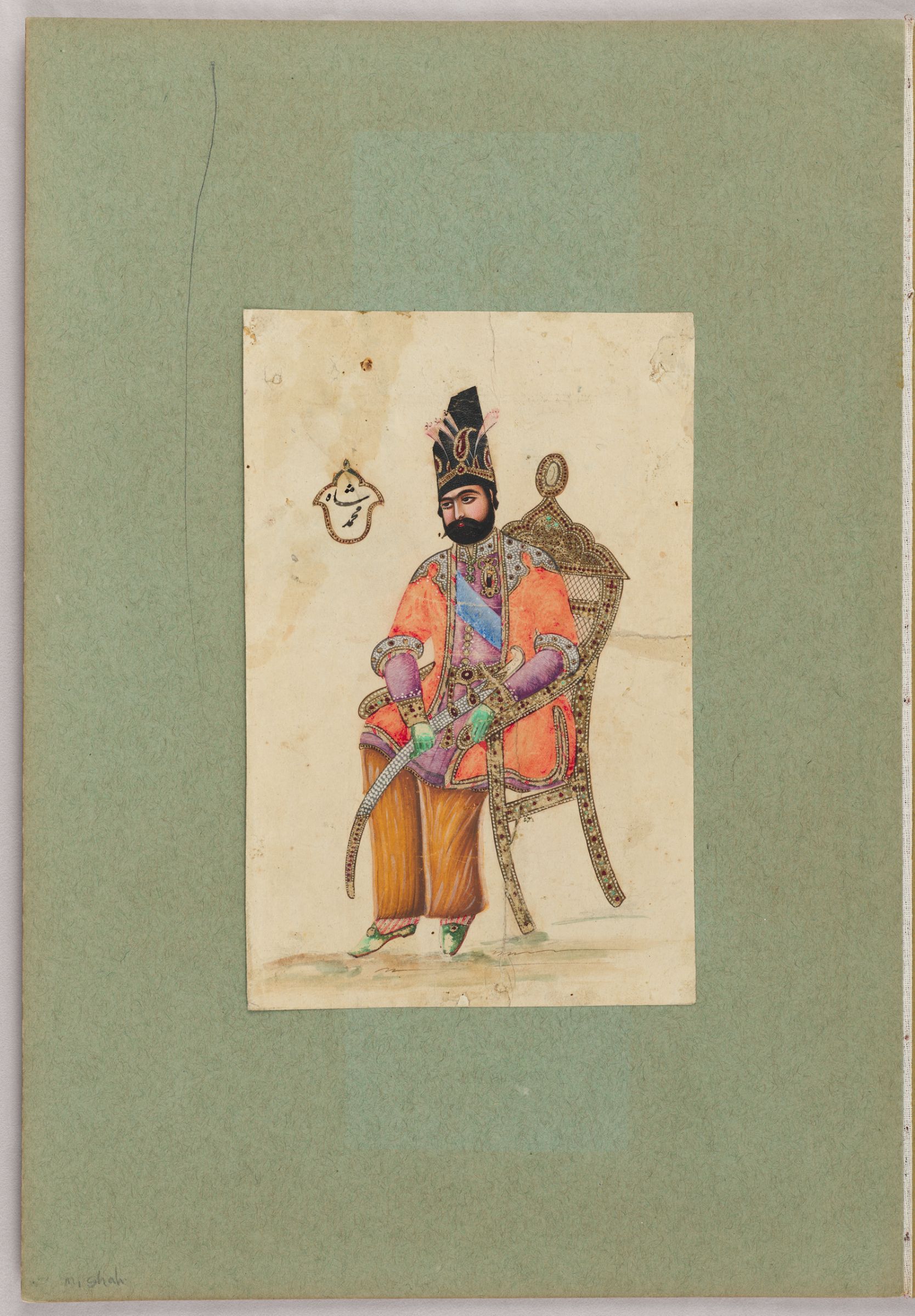

Though it took a few more years, Roxburgh got his chance. In the spring of 2015, he taught a graduate seminar focused entirely on the album, which is an assembly of works produced during Iran’s Qajar dynasty. (The album is known in shorthand as the Harvard Qajar Album.) McWilliams, the Norma Jean Calderwood Curator of Islamic and Later Indian Art at the Harvard Art Museums, led a number of class sessions as students and teachers alike sought to learn more about the images contained within this unique object.

Now, two years later, McWilliams and Roxburgh have co-curated the exhibition Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran (August 26, 2017–January 7, 2018), which includes works from the album and builds upon the critical scholarship that emerged from Roxburgh’s class. The exhibition “looks at many of the fascinating connections between Qajar artists, art forms, and new technologies in 19th-century Iran,” McWilliams said. This period witnessed significant social, cultural, technological, and political change in Iran, as well as an increased involvement on the global stage. Those developments stimulated and supported an era of heightened image-making and image-sharing. The album—as well as the approximately 75 other drawings, paintings, lacquer objects, lithographs, and photographs in the exhibition—attests to the interconnectedness and mobility of images produced in Qajar Iran.

Remarkable Object

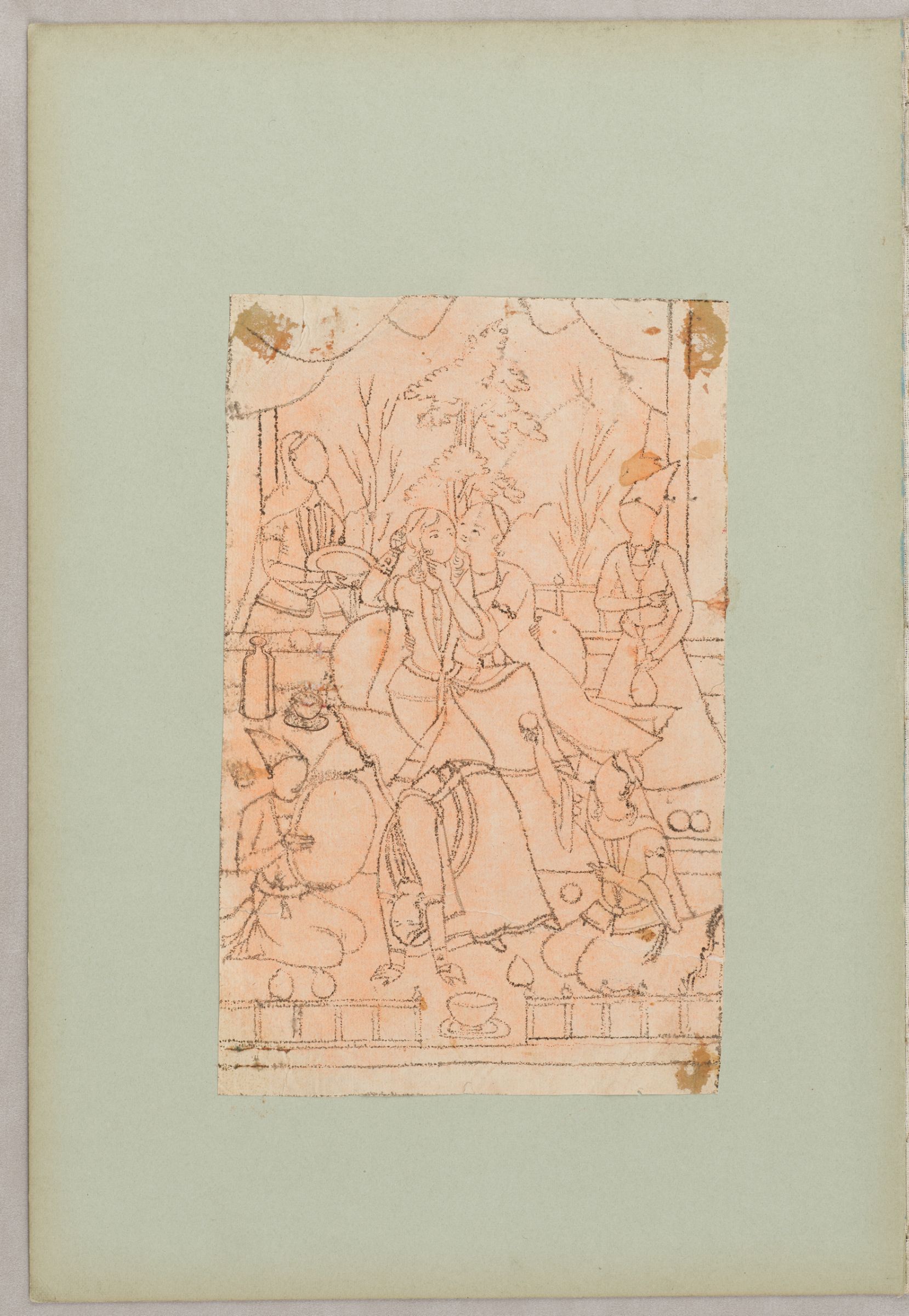

The album is a wellspring for academic study. Its 57 folios contain technical materials that point to the wider system of artistic production and exchange in place at the time. Because artists used such materials in their daily work, most were damaged and subsequently discarded.

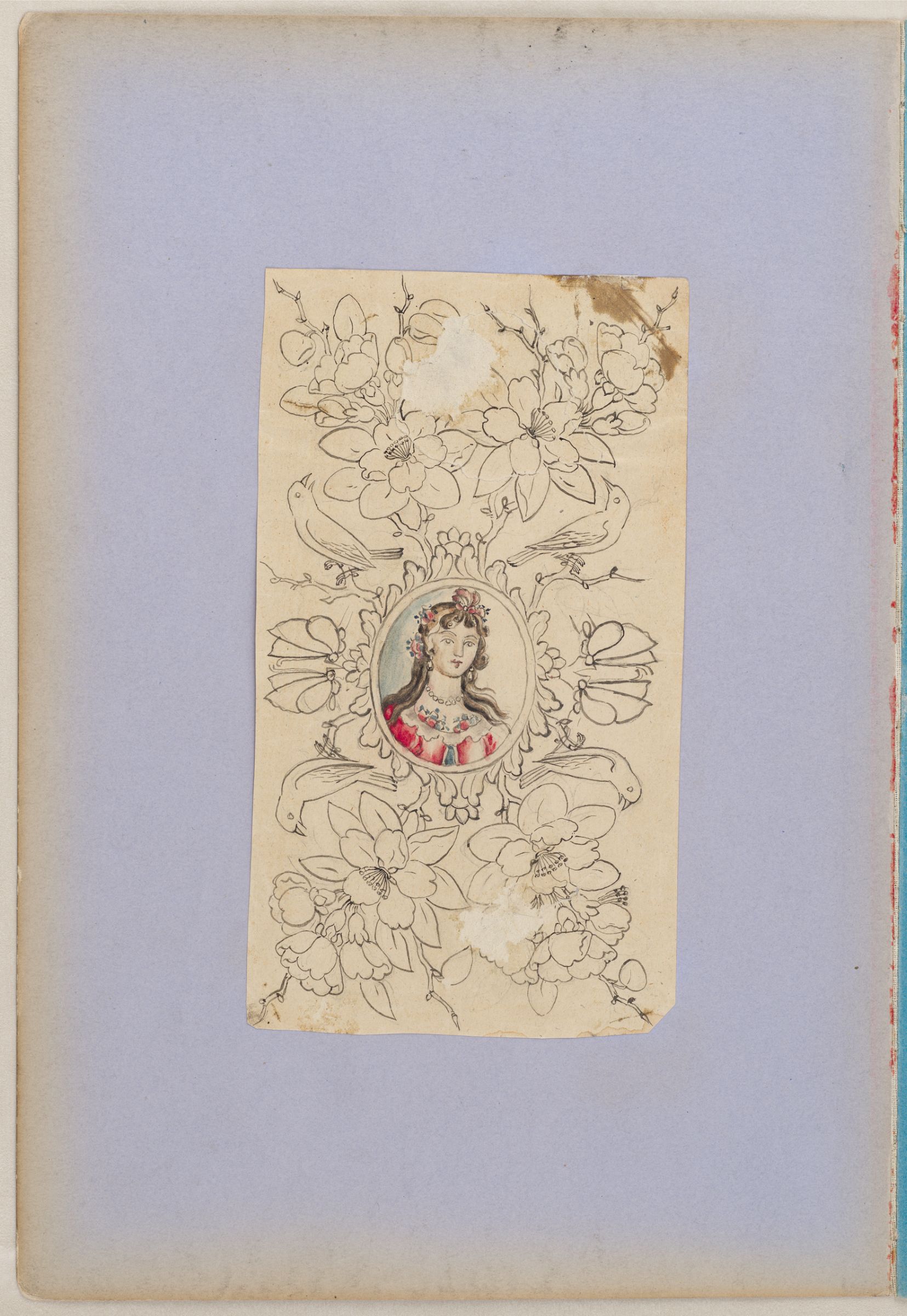

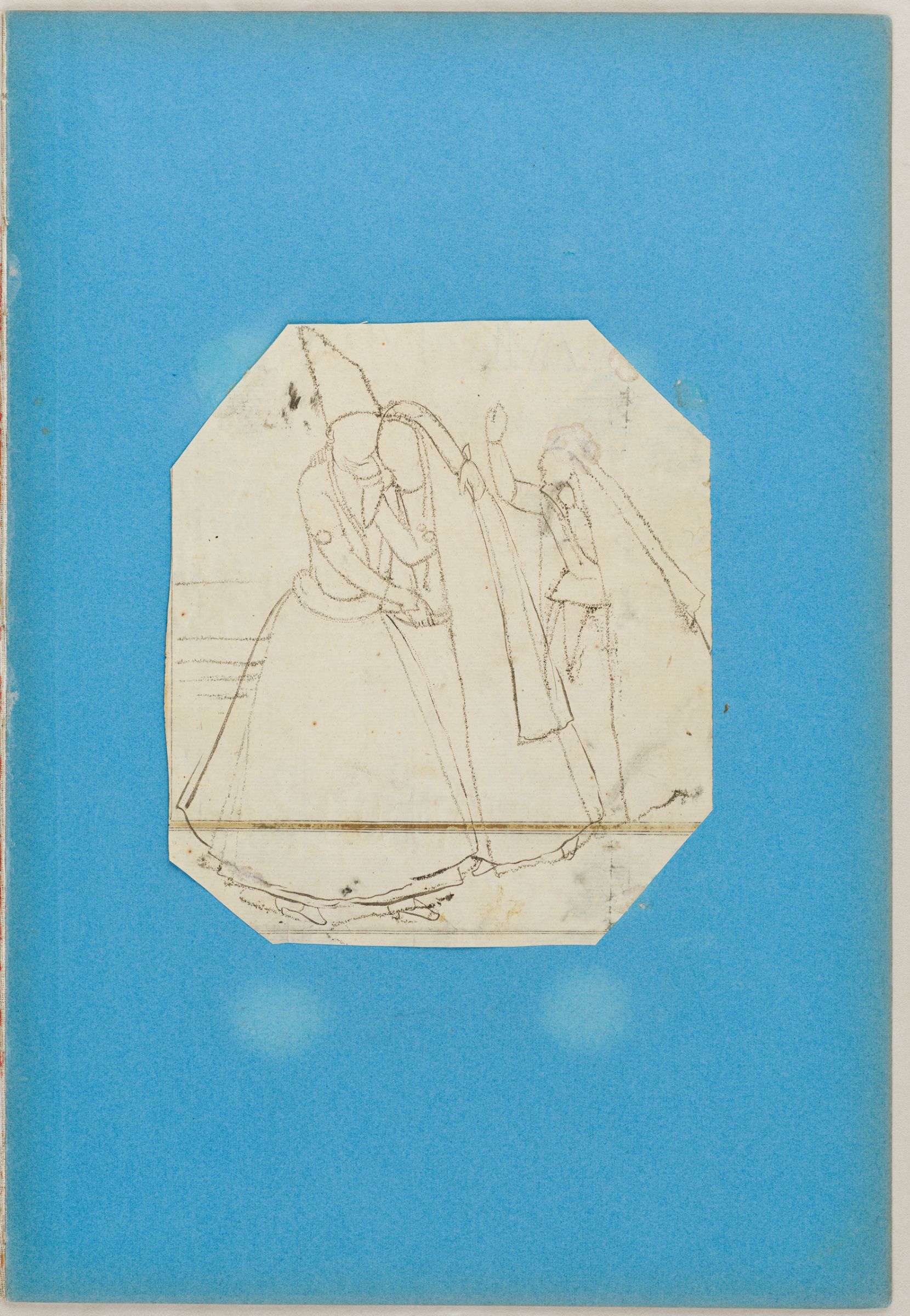

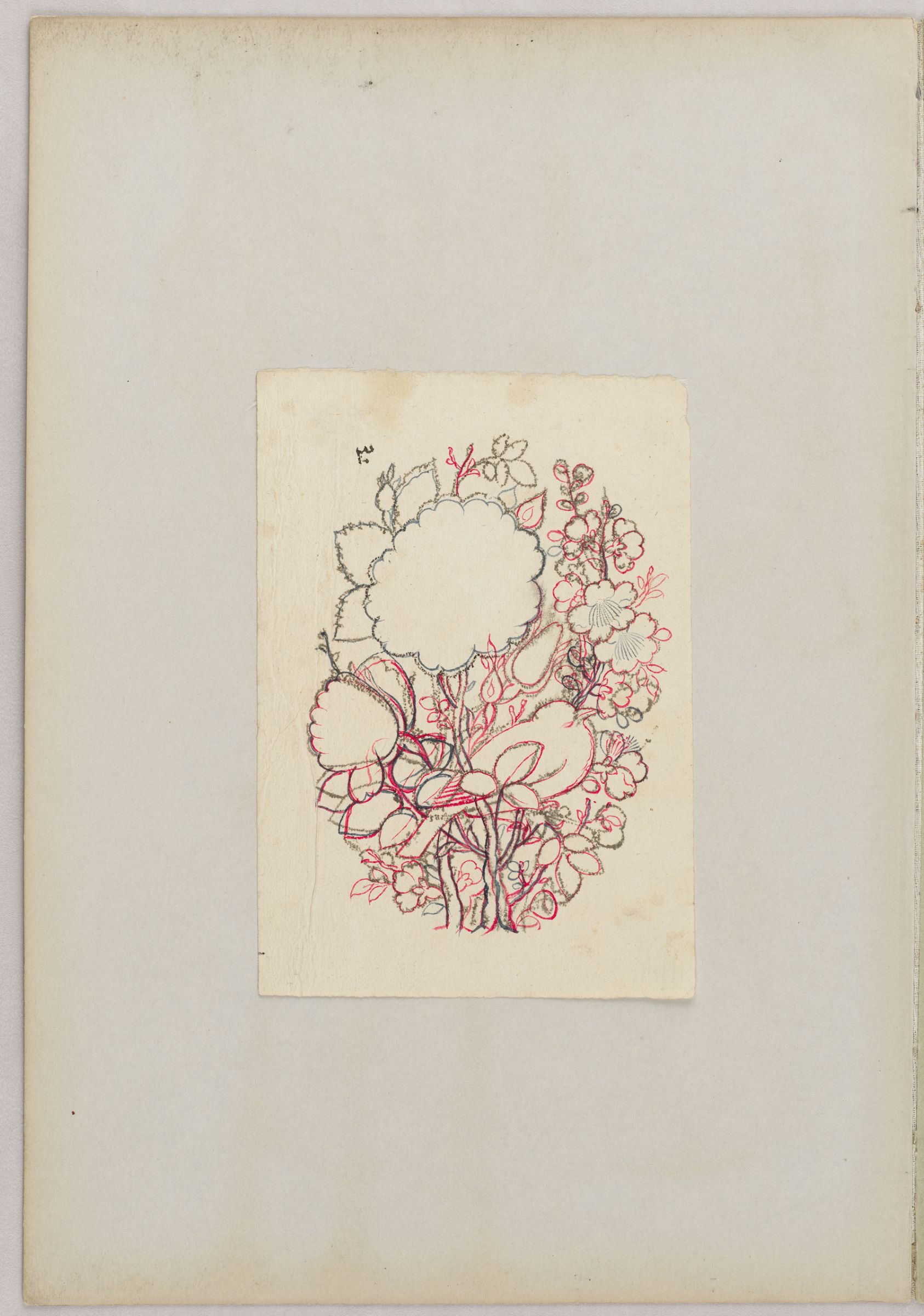

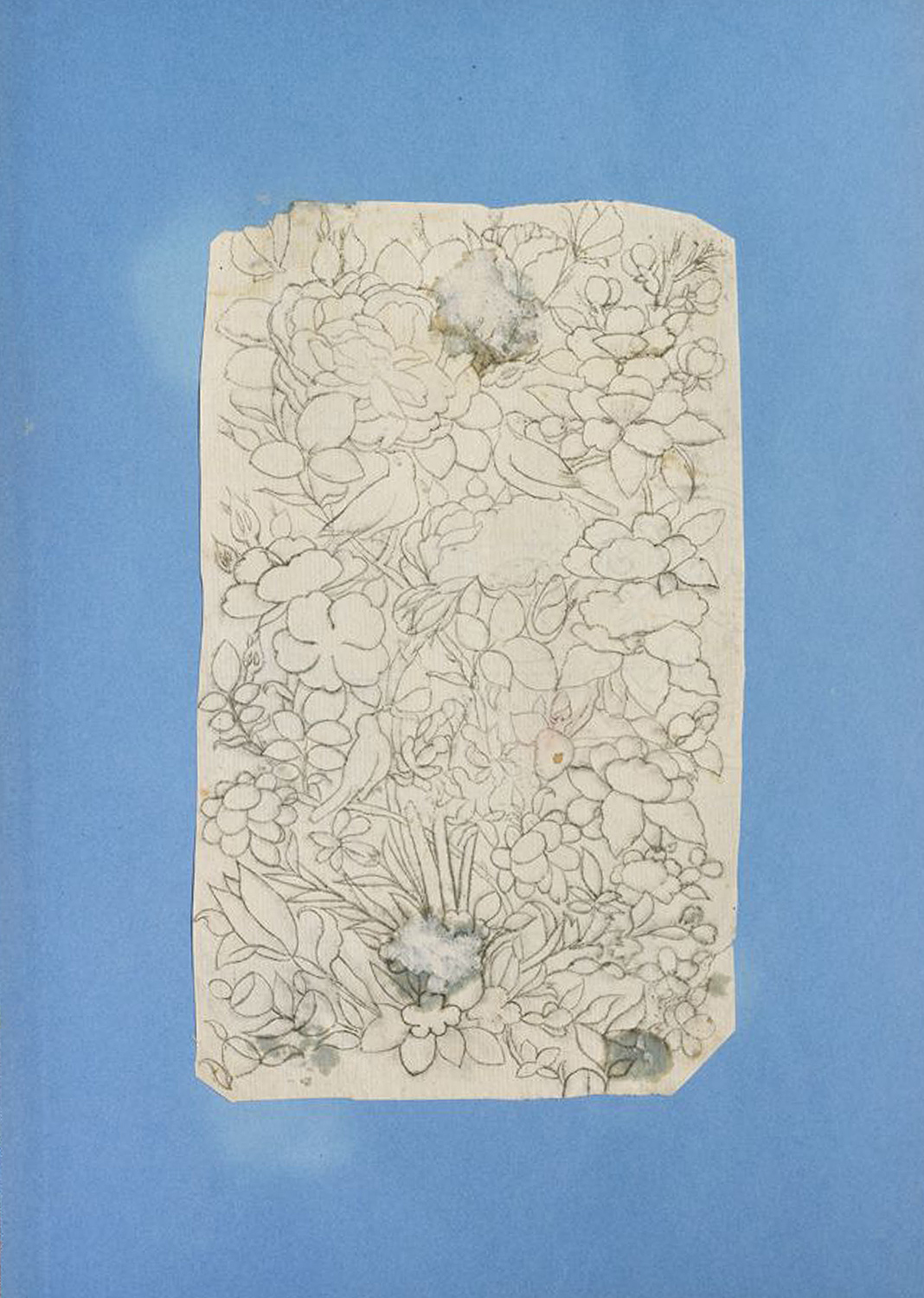

“In Iran, as elsewhere, copying the work of past masters was a long-standing tradition,” McWilliams said. Outlines of artworks and designs (some of which were themselves copied or inspired by other sources, such as European paintings) were prepared for reproduction through various techniques.

Students in the seminar learned about several of those techniques by emulating them. Francesca Bewer, research curator for conservation and technical study programs, led the students in a Materials Lab session in which they experimented with ink transfer methods. Students were also able to practice the technique of “pouncing,” in which translucent paper is laid atop a finished image or outline, and tiny holes are pricked on the paper that correspond with the outline beneath. An artist could then place the pricked paper on top of a blank sheet and force chalk or another substance through the holes to create a new outline.

The students also learned how experts analyzed and even dated the materials included in or related to the album. Penley Knipe, the Philip and Lynn Straus Senior Conservator of Works on Paper, and Katherine Eremin, the Patricia Cornwell Senior Conservation Scientist, in the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, led discussions related specifically to the album’s materiality and the composition of various other related objects (such as lacquer boxes).

These sessions proved fruitful for the conservators’ own research. For instance, Knipe said the students’ observations helped her identify watermarks on dozens of pages in the album, which revealed that some of its papers had been imported from Europe.

Vital Links

The close study of certain preparatory sketches and templates in the album was key to understanding other works of art from the same period as well. For example, one drawing from the album, Birds and Flowers (c. 1775–1850), shown below, was found to have served as a model for multiple objects. These include a distinctive and colorful lacquer mirror case (now in a London collection) that was signed by the celebrated 18th-century artist Muhammad Sadiq. A somewhat later work in the exhibition, the lacquer Rectangular Mirror Case with Bird, Flowers, and Two Butterflies (first half 19th century), also shown below, repeats the design in reverse. Such pairings are included in the Technologies of the Image exhibition, so that viewers may compare their striking similarities.

These sorts of connections—though made explicit in the exhibition—might not be initially evident to a casual viewer. But for the students and experts who spent months closely studying the album and producing new scholarship, they became abundantly clear.

“The album opens up a view into how art was produced in the Qajar era and how it changed,” said Mira Xenia Schwerda, a Ph.D. candidate in Middle Eastern studies and the history of art and architecture who took the class. (Schwerda contributed to the accompanying book An Album of Artists’ Drawings from Qajar Iran, which features essays written by students in Roxburgh’s class.) “Studying the album helped me more clearly understand the connections between different artists’ materials and methods.”

Schwerda focused her research for the class on depictions of domesticity, as the album contains many drawings of women and children in private settings. She said that the album made her realize “how mobile images are, and how they not only go from place to place but also change from medium to medium, and are reinterpreted along the way.”

Roxburgh and McWilliams hope that visitors to the Technologies of the Image exhibition can glean similar lessons through close examination. “These objects require a particular, sustained attention,” Roxburgh said. “But they repay the time spent looking at them.”