After delicately unrolling an Asian hanging scroll and placing it on the wall of the Art Study Center, Elizabeth Sirrine stepped back and smiled. “What’s amazing about the Art Study Center is that we’re afforded the opportunity to make art accessible to everybody,” she said. “That’s probably what I love most about working here.”

Handling the Art

Sirrine is an art handler at the museums, one of five staff members in the Collections Management department trained to handle and display works of art for visitors to the Art Study Center. The Art Study Center allows individuals or small groups to study almost any work from the museums’ collections that is not currently on display. Most visits are by appointment, which can be requested on our website. On Mondays, from 1 to 4pm, visitors are welcome to drop in and request an object to view.

On a busy day, Sirrine and her colleagues can transport and display works of art for up to 15 separate Art Study Center appointments. Each appointment may require art handlers to retrieve dozens of works of varying shapes, sizes, and media from the museums’ vast storage spaces. Art handlers remain in the room as visitors view the objects—sometimes, they even field questions (although most get redirected to curators or conservators).

All of these responsibilities mean art handlers must not only serve as a friendly and knowledgeable face for the museums, but also navigate the tightly controlled behind-the-scenes spaces. “It’s a dynamic job,” Sirrine said. “We never experience the same day twice.”

Retrieval and Transportation

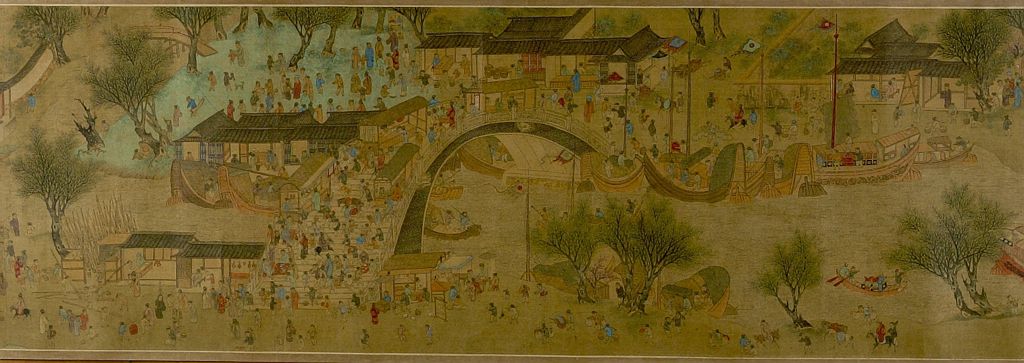

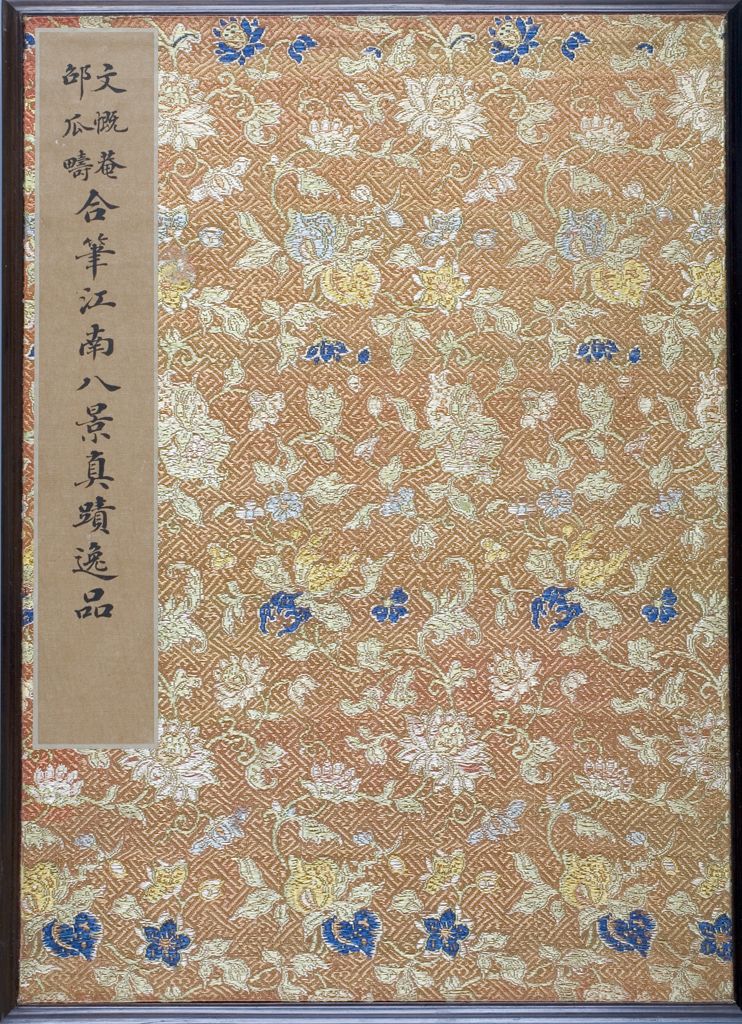

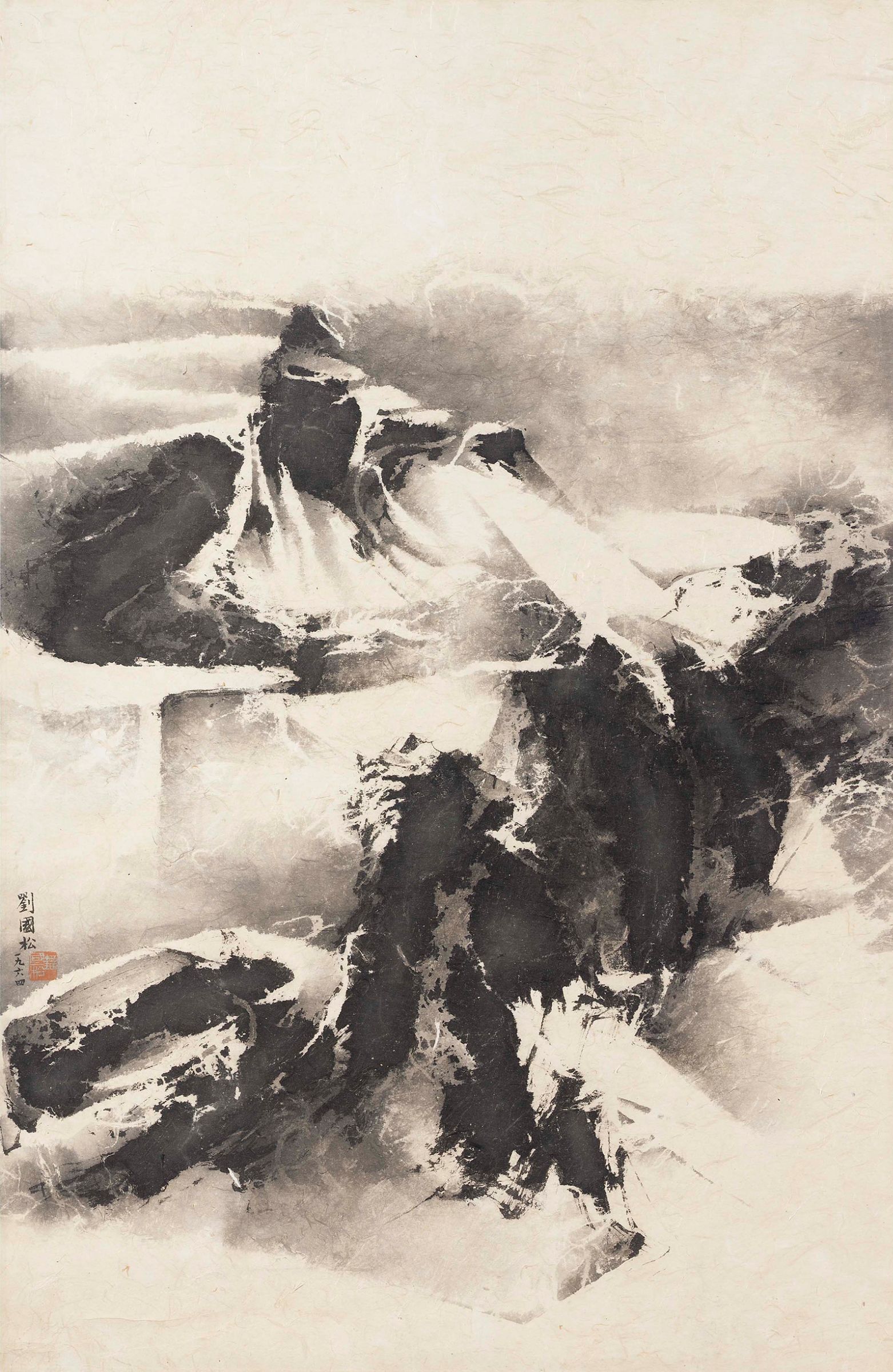

Like all art handlers, Sirrine typically starts her day by reviewing that day’s hourly schedule, arranged in advance by colleagues who process visitor appointment requests. On a recent morning, just a few Art Study Center appointments were scheduled; Sirrine was tasked with setting up the display of objects for one of them, which required transporting a number of Asian works, including handscrolls, hanging scrolls, and an accordion book (see a few in the slideshow below).

She began by studying each object’s accession number, a unique identifier for an individual work. In the museums’ digitized cataloguing system, each accession number corresponds with a barcode on an individual object’s box, frame, or other housing material, which in turn corresponds with a specific permanent storage location. (These codes are digitally united by staff members using a handheld scanner; when an object is moved, a few quick scans register its new location.)

Next, Sirrine pulled out a rolling storage cart and took the security-controlled elevator to the basement. From a nondescript corridor that leads to multiple storage rooms, she entered a cavernous space filled with three-dimensional objects.

Careful transportation of objects is paramount to Sirrine’s job. “We would never walk far with a work of art, and you would definitely never see us, for instance, walking up the stairs holding an object,” she said. “We always want to minimize the amount of time we are handling an object.”

Sirrine brought her cart directly next to a large set of drawers containing small boxes. She skimmed the boxes’ bar codes for the accession number of her first object. To an untrained eye, this process—not unlike searching the library stacks for a call number—could take a while. But within seconds Sirrine found what she needed, added it to her cart, and then repeated the process until all five objects were ready to be transported upstairs.

Preparing for Visitors

In a temporary storage room back in the Art Study Center, Sirrine scanned each object’s code along with the Art Study Center’s location code, ensuring that digital records were updated. Then, she rolled the cart into an empty seminar room and prepared to display the objects.

She stretched custom-made canvas and muslin covers over a table, to provide a softer surface for the centuries-old objects. To display the hanging scrolls on tiny wall hooks, she used a long, stick-like tool (a traditional method, which also minimizes the amount of direct contact she makes with the object).

“What’s amazing about the Art Study Center is that we’re afforded the opportunity to make art accessible to everybody.”

Even when encountering such a diverse range of art, Sirrine said she feels secure in her art handling skills. But when she occasionally does feel overwhelmed—by a work’s importance, by the size or weight of an object, or even by the expectations of visitors—she slows down.

“You never want to feel rushed,” she said. “Slowing down is essential. I also find it very helpful to bring in another colleague—another art handler or even a curator or conservator—who can assist in answering any questions visitors may have.”

Pausing to look at the art she arranged, Sirrine recalled some of the visits to the Art Study Center she’s overseen during her two years on the job. She’s watched as high school students closely studied an assortment of prints, a professor pored over Italian Renaissance drawings in weekly sessions, and curatorial staff meticulously catalogued sherds of ancient ceramics. Recently, she said, she was touched to see a husband arrange an Art Study Center visit for his wife’s birthday, so his wife could view works by her favorite artist. “She was completely stunned,” Sirrine said. “It was wonderful to be a part of that special moment.”

Perhaps the biggest surprise she’s encountered on the job has been the diversity of visitors to the Art Study Center. “When I first started here, I was under the impression that the majority of appointments would be for Harvard students and faculty, but that’s not the case at all. The Art Study Center caters to everyone, from art historians to students and residents in the greater Boston community,” Sirrine said.

“It doesn’t matter who you are, or what your level of education is; it just matters that you’re interested in viewing and learning more about art.”