In 1948, Harvard University commissioned the Cambridge architecture firm The Architects Collaborative to design the Harvard Graduate Center, a complex of seven dormitories and a student center. It opened two years later to international acclaim as the first example of modernist architecture on campus.

The complex was the first major American project by its lead architect, Bauhaus founder and Harvard architecture chair Walter Gropius. Not limiting his modernism to the building’s design, Gropius raised additional funds to commission site-specific art for the center’s public spaces from leading modern artists, including former Bauhaus colleagues Josef Albers and Herbert Bayer, American sculptor Richard Lippold, and Spanish painter Joan Miró. Hans Arp, a founder of Zurich Dada and an outspoken advocate of abstract art in the immediate postwar years, contributed the room-sized relief Constellations to the project.

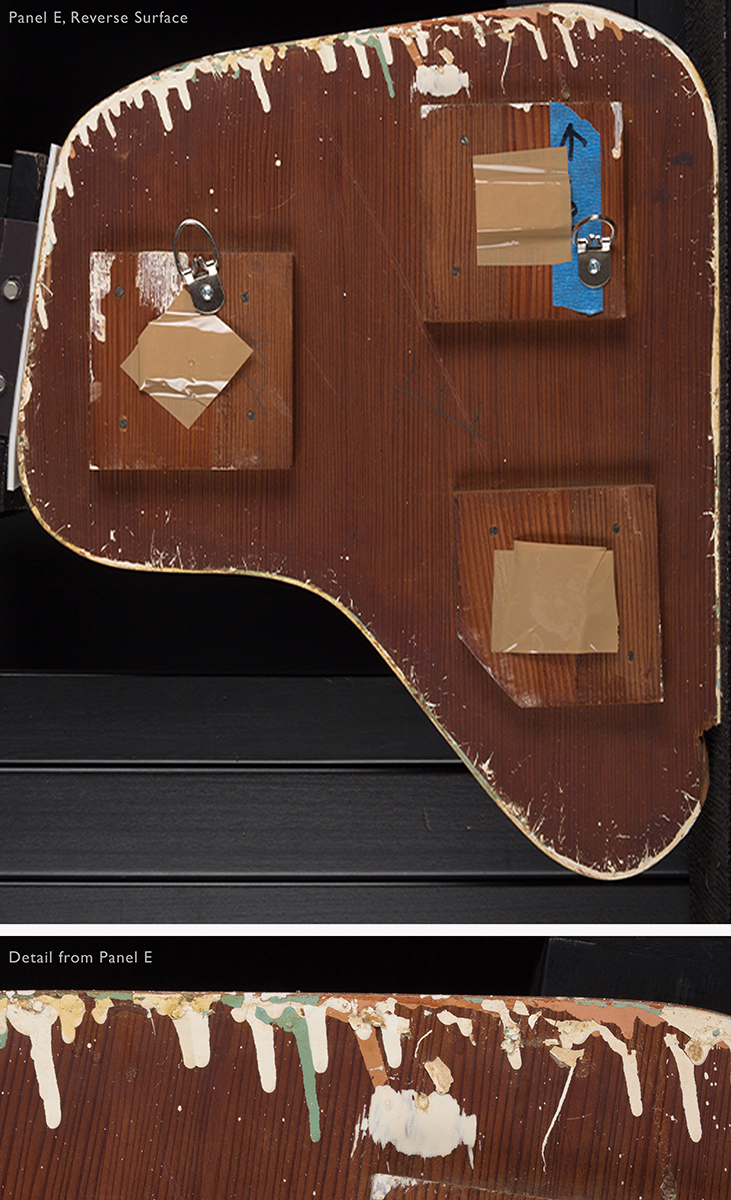

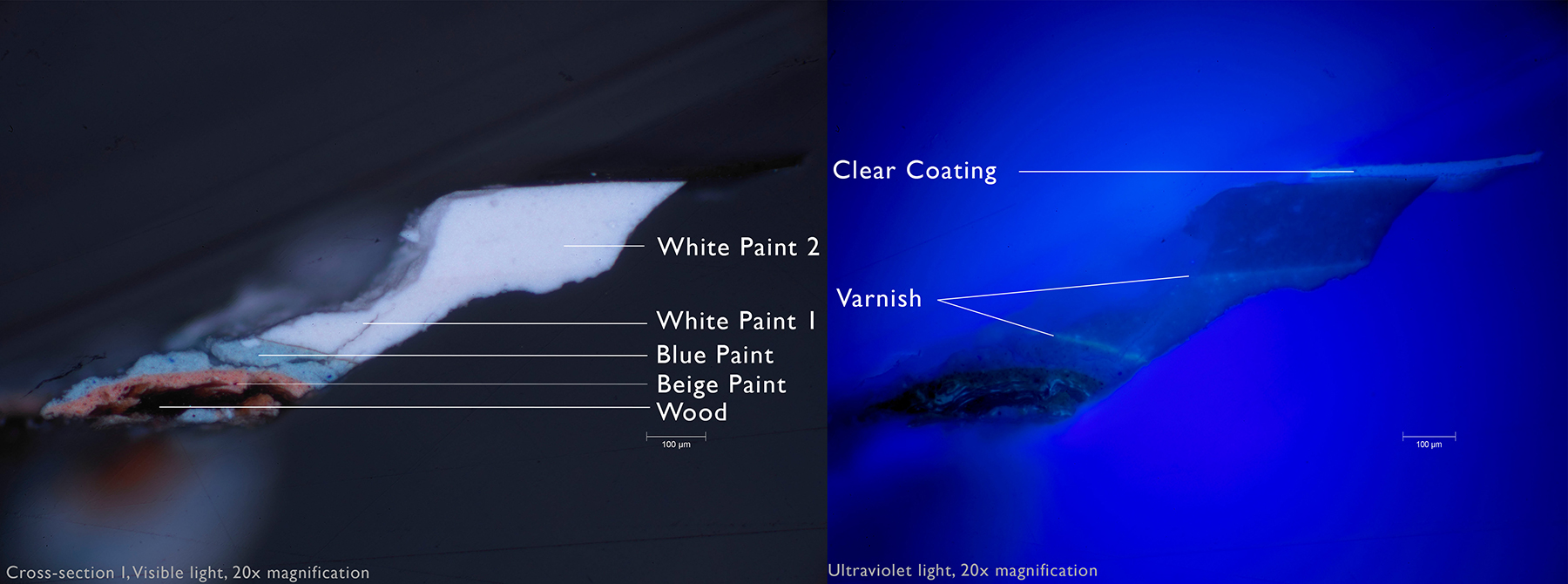

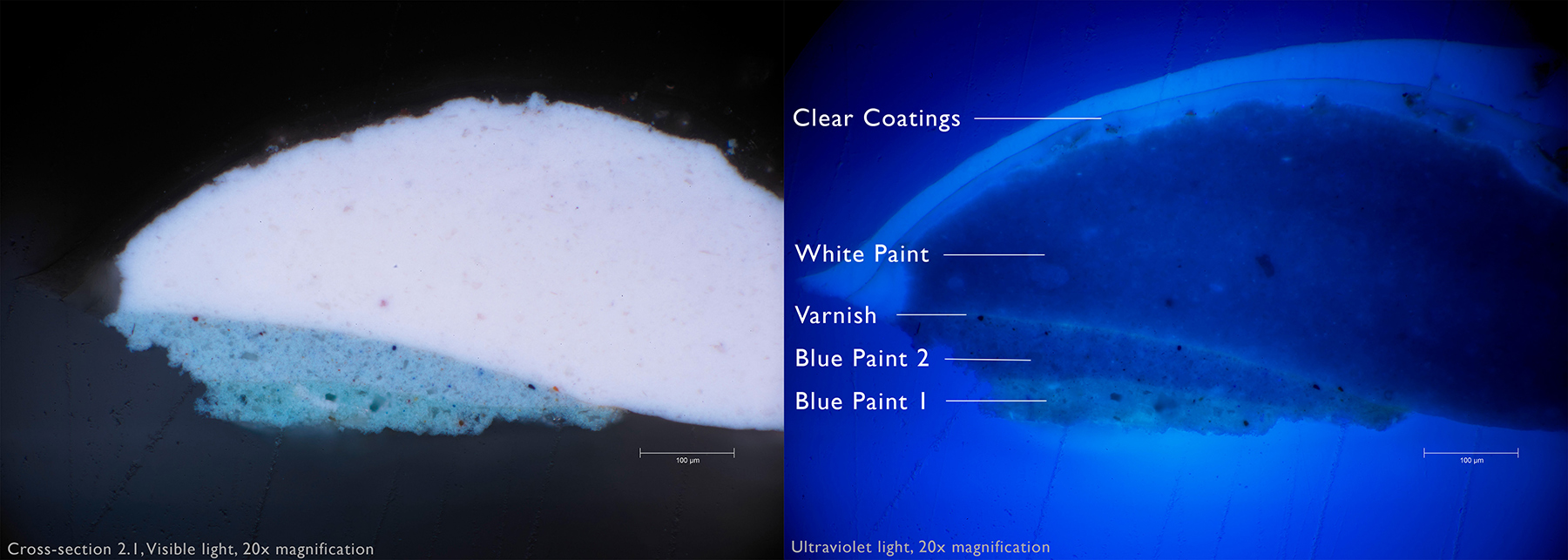

Over the past year, Arp’s Harvard relief has been the focus of a conservation and research initiative that has reconstructed its physical history and uncovered decades of correspondence between Gropius and Arp. These new findings informed a historically accurate restoration of the relief that re-creates its original finish, the results of which will be unveiled in the exhibition Hans Arp’s Constellations II opening in February 2019. This research has revealed previously undiscovered facets of this fascinating object and its rich history.

The Commission and Design

Gropius and Arp had never met but shared a mutual friend in architectural historian Sigfried Giedion, who recommended Arp for the commission. All three were active with the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM), a gathering of modern architects whose debates about the role of art in architecture informed Gropius’s decision to commission art for the Graduate Center. Giedion and Arp co-authored an influential statement on the integration of art and architecture for CIAM in 1938 and were revising it when Gropius approached Giedion for recommendations.

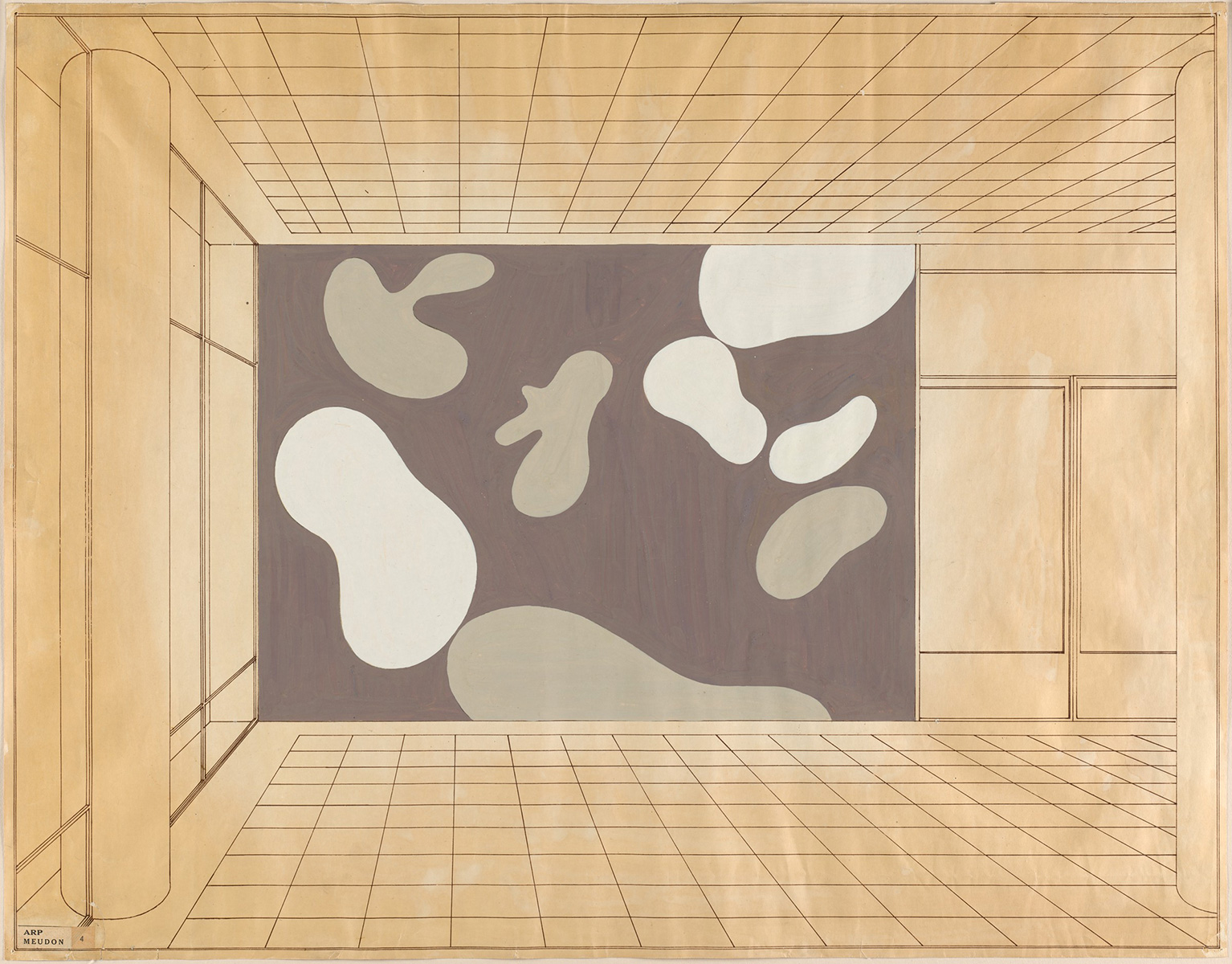

Arp’s sophisticated ideas about designing site-specific art for modernist interiors made him an enthusiastic commission partner. But the project’s small budget meant Arp had to prepare his designs from his cramped studio in France without access to the site, a dormitory recreation room. Gropius sent Arp architectural plans and photographs of the space; in return, Arp reluctantly submitted multiple designs of his relief accompanied by more questions about the interior. Gropius’s feedback prompted a new round of designs (now in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums).