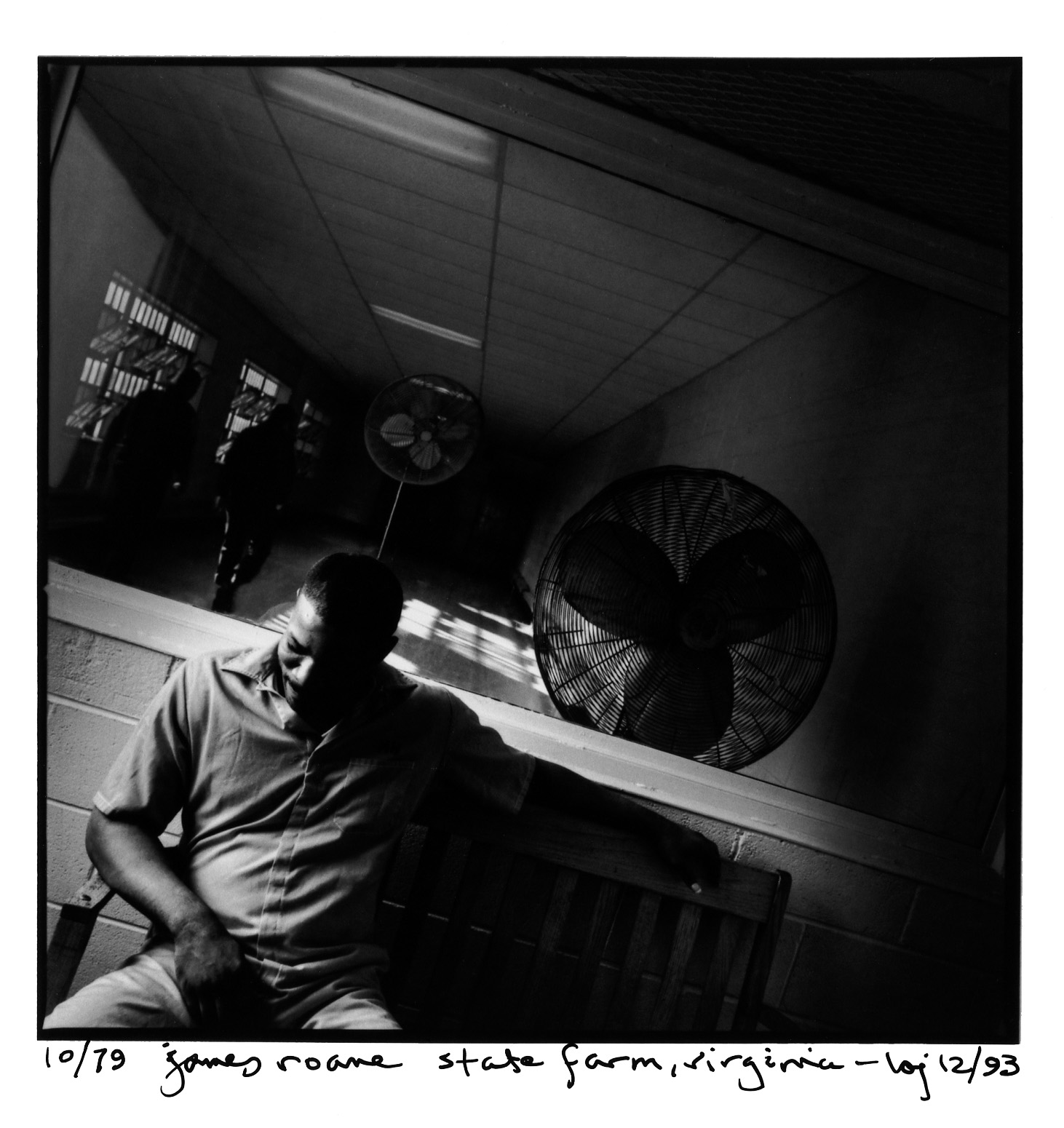

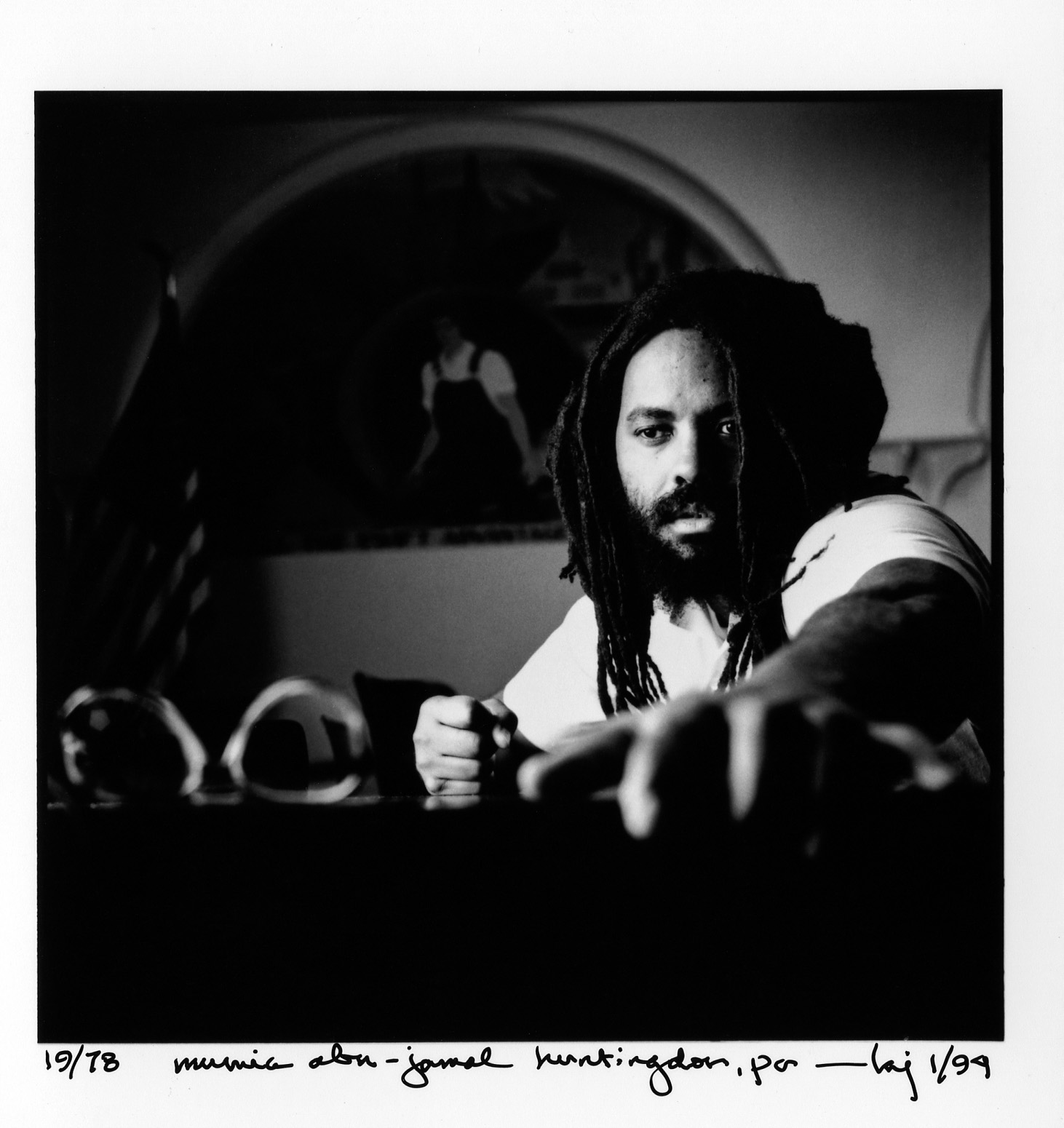

Have you ever peered into the eyes of another human who knows they are—and whom you know is—legally sanctioned to be killed?

Photographer Lou Jones spent years capturing the gaze and humanity of death row inmates across the United States with his cameras and tape recorder, compelled by a deep-seated belief that capital punishment is morally wrong.

“Basically, the idea is to give you an identity,” Jones explained to Marko Bey, one of the inmates who agreed to be photographed for the Death Row series. Jones’s assistant and key collaborator, Lorie Savel, who conducted the interviews of the 27 prisoners while Jones photographed, notes that the project aimed to find “a way to get the pro-[capital punishment] thinkers to open their minds.”