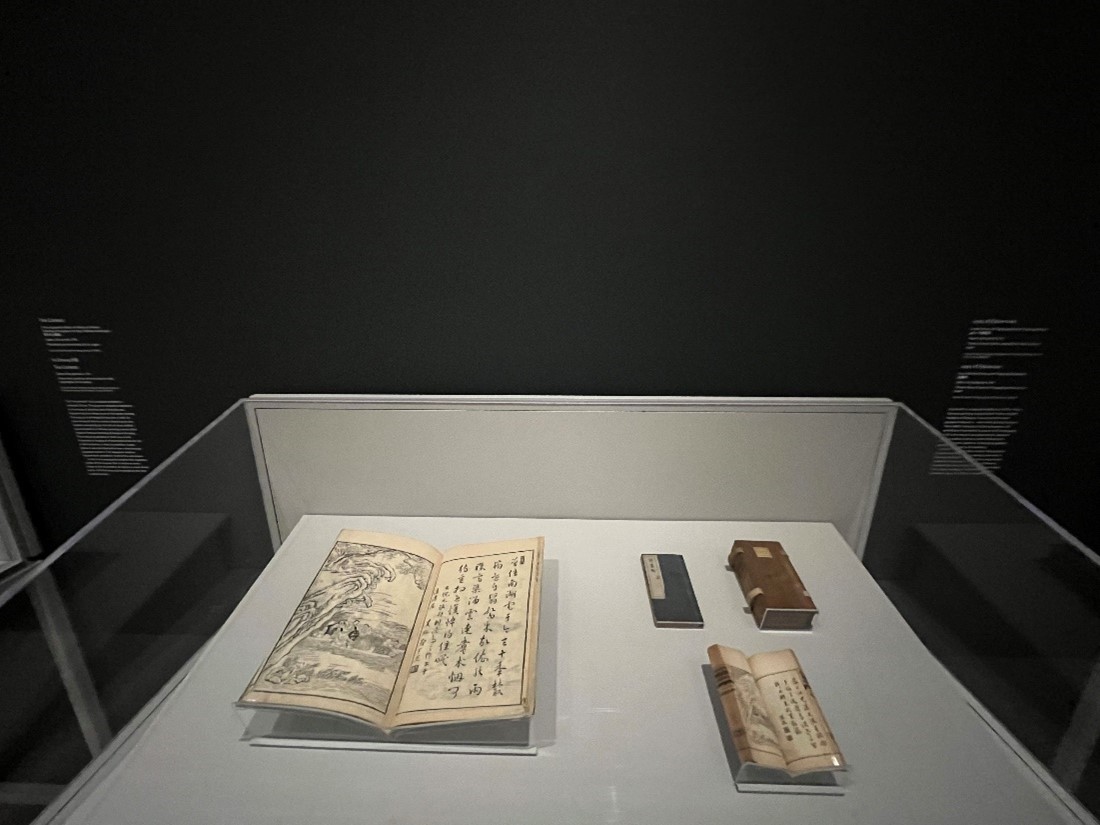

Art by the Book, on view through June 4, 2023, is the first installation of woodblock-printed painting manuals at the Harvard Art Museums.

What is most remarkable about these types of Chinese painting manuals (Chinese: huapu 畫譜) is the variety of functions they served. They were instruction manuals, but they also were symbols of refinement and were art forms in and of themselves, like portable galleries of art made accessible to a large audience. The manuals were produced through the collaborative efforts of more than a hundred artists and artisans, ranging from painters to woodcarvers, poets, calligraphers, and printers. In the 16th and 17th centuries, painting manuals would be purchased by the emergent upper social classes—wealthy merchants and urban elites—and would also be exported to neighboring Korea and Japan. Owning one of these manuals signaled sophisticated taste and intellectual pursuits.

We sat down with Yuhua Ding, who organized Art by the Book when she served as a curatorial fellow in East Asian art at the Harvard Art Museums, to discuss the installation in detail.

Index: Was woodblock printing in 16th- and 17th-century China considered a lower tier of painting? Where did woodblock printing fit in the art hierarchy?

Yuhua Ding: In terms of art practices, woodblock printing and Chinese ink brush painting were quite different. The publication of painting manuals such as the Ten Bamboo Studio Manual of Calligraphy and Painting was aimed originally to imitate ink painting at its best.

As scholars such as J. P. Park have already pointed out, the apex of painting manual culture in 17th-century China was associated with the rapid development of woodblock printing and the increasing public desire to acquire artistic taste, knowledge, and sensibility—a prerequisite of elite status. In other words, painting manuals should not be recognized solely for their use as instruction materials. Through a combination of image and text, painting manuals demonstrate their multiple social and artistic functions: they are the oldest illustrated catalogues of Chinese master paintings, and they play a key role in cross-cultural communication within East Asia.

It is also worth noting that the introduction of lithography in the 19th century challenged Chinese traditional woodblock printing. For Art by the Book, we selected seven hand-carved woodblocks that were used to make a pirated copy that imitated a lithographic original. The selection might lead us to rethink woodblock printing from both a sociopolitical perspective as well as an artistic and technical one.