With this insight from the workshop participants, I started to consider my original hypothesis from a different perspective. Manet had made a series of technical and material decisions with gillotage in mind, yes, but what other avenues of inspiration did gillotage have in mind for Manet?

Sarah Mirseyedi is a Ph.D. candidate in the history of art and architecture at Harvard and was a graduate student intern in the Materials Lab from September 2018 to May 2019.

[1] For more on this drawing, see Carl Chiarenza, “Manet’s Use of Photography in the Creation of a Drawing,” Master Drawings 7 (1) (Spring 1969).

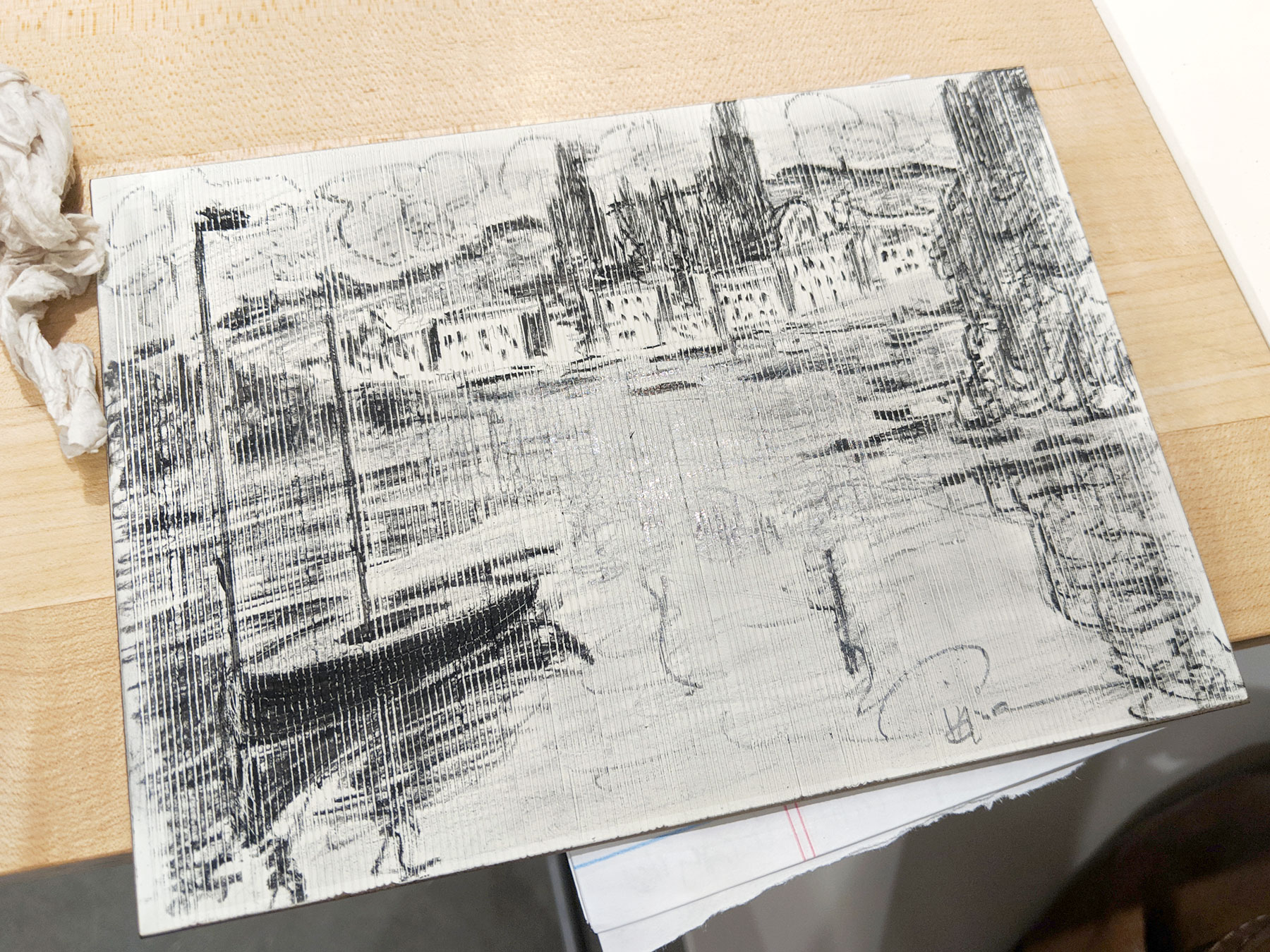

[2] For more on Gillot paper, see Kenneth M. Grant, “The Forensic Examination of Drawings: Three Case Studies in Technical Observation of Works on Paper,” in Storied Past: Four Centuries of French Drawings from the Blanton Museum of Art, ed. Cheryl K. Snay (Austin: Blanton Museum of Art, 2011), 146–48.

[3] Sarah Mirseyedi, “Reproduction,” in Drawing: The Invention of a Modern Medium, ed. Ewa Lajer-Burcharth and Elizabeth M. Rudy (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Art Museums, 2017), 244–55.

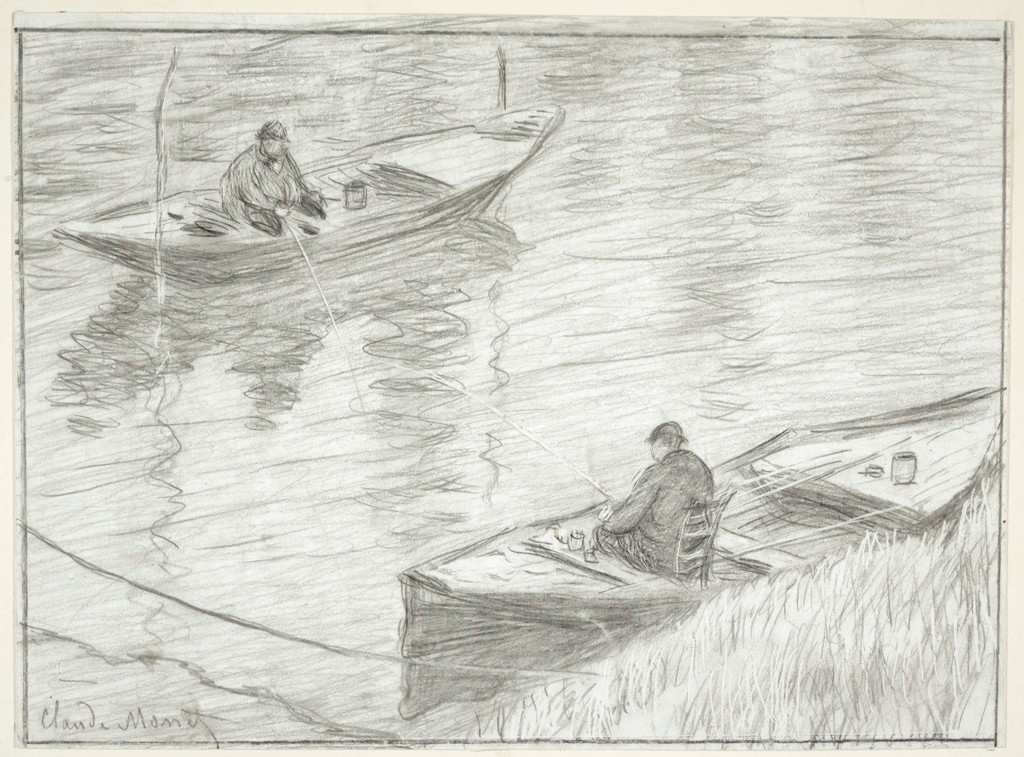

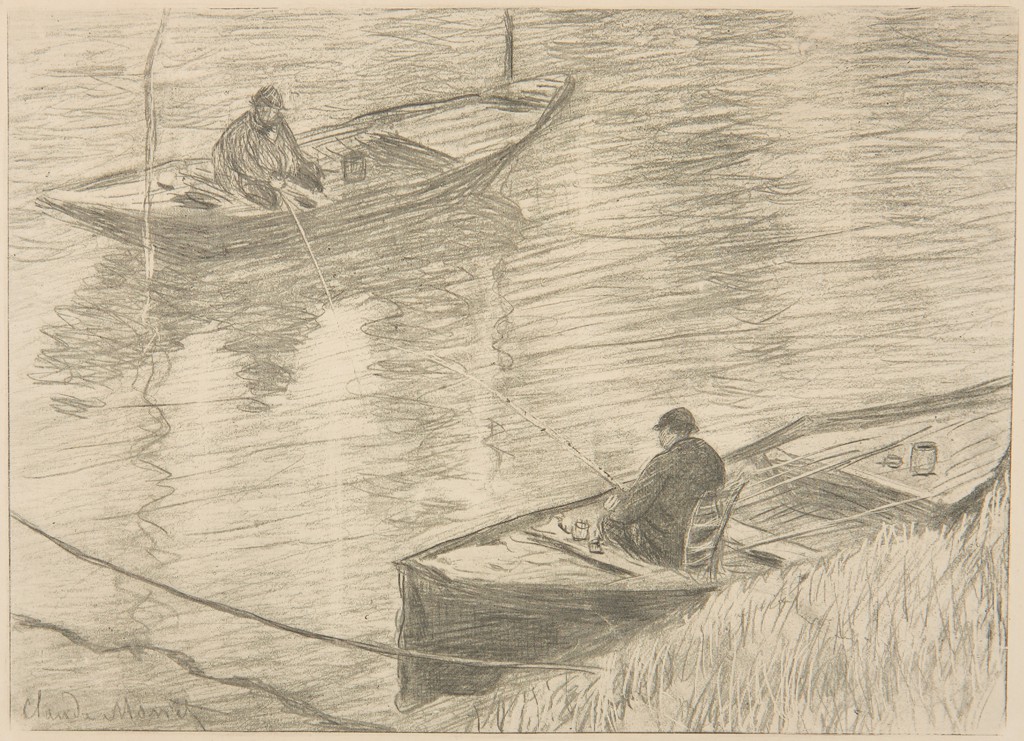

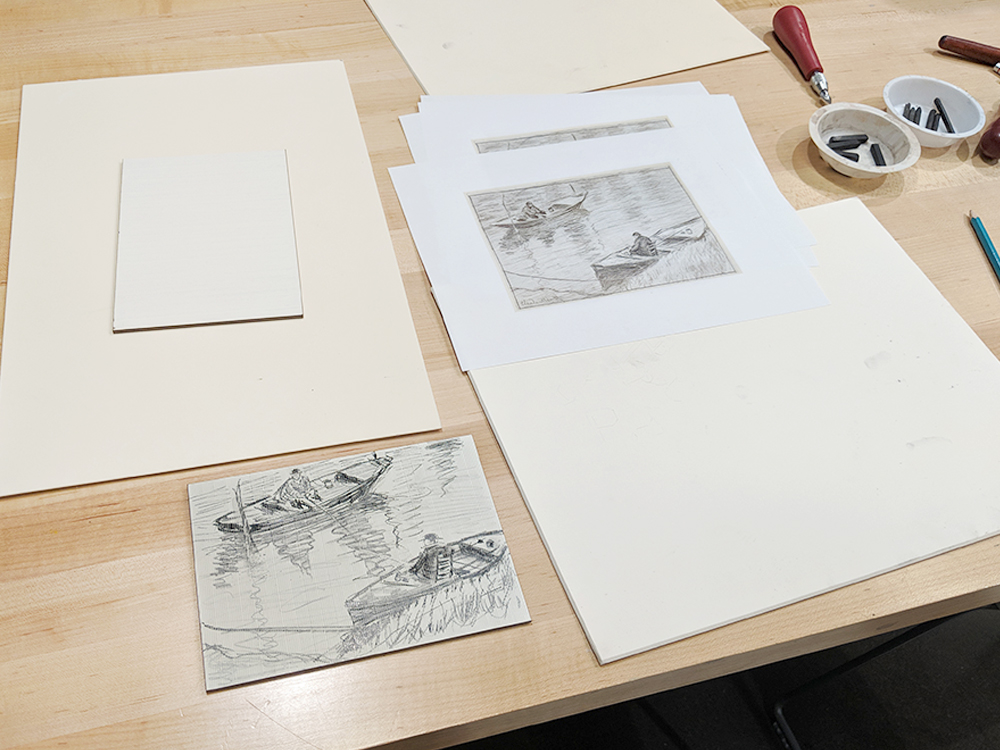

[4] James A. Ganz and Richard Kendall, The Unknown Monet: Pastels and Drawings (Williamstown, Mass.: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2007), 199.

[5] In January 1896, Scribner's Magazine published a wood engraving after Monet's painting View of Rouen (1872). Much as he had done for Two Men Fishing, Monet had earlier made his own drawing after View of Rouen on Gillot paper, which enabled the drawing to be reproduced by gillotage for the Gazette des Beaux-Arts in 1883. Workshop participants were able to compare the more traditional wood-engraved reproduction against the reproduction made through the photomechanical gillotage process, thanks to these loans from Harvard libraries. For more on these two reproductions, see Ganz and Kendall, 196–97.