At first glance, Carl Grossberg’s Marktbreit seems to offer a serene, photorealistic view of a Bavarian village. Real-life landmarks—the bell tower of St. Nikolai and the ornate facade of Marktbreit Palace—stand out against the pitched roofs and jutting chimneys. But all is not quite as it seems.

Carl Grossberg in Context

“There are elements in this painting that do not make sense spatially—some shadows, for instance, are exaggerated, and there are inconsistent light sources,” said Melissa Venator, the Stefan Engelhorn Curatorial Fellow in the Busch-Reisinger Museum. “These discrepancies make you pause and think more deeply.”

A viewer might pick up on other unusual details in the painting, such as the central placement of an electrical pole and the conspicuous absence of people; the pole is an unexpectedly modern element in a landscape from an earlier century.

Those aspects of the work demonstrate Grossberg’s unique stance within the German art of Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity, whose artists shared a renewed engagement with realism. While Grossberg’s verisimilitude, attention to detail, and high degree of finish aligned him with this interwar style, he combined this approach with less conventional techniques, including turns of surrealism, as with the electrical pole in Marktbreit.

A temporary two-part installation—the first of which is on view now—offers a glimpse into Grossberg’s world, and for most visitors, an introduction to the artist. Grossberg was a successful painter and interior designer in Germany during his short lifetime (he died in 1940, at the age of 46), but his art was kept in the family until recently. The installation is the first monographic presentation of Grossberg’s paintings, drawings, and lithographs in the United States, and is made possible through generous loans from the Merrill C. Berman Collection. The second installation will go on view in December.

An Outstanding Collection

Berman, Harvard Class of 1960, began to collect Grossberg after works were released on the market in the early 2000s. He estimates that he owns nearly 20 works by Grossberg, which complement his extensive collection of avant-garde graphic design and modern German art.

“You just can’t find an undiscovered giant from the 1920s like this anymore,” Berman said. “Grossberg had broad talent. If he were in the United States, he would be lionized like [American precisionist painter] Charles Sheeler. But there’s no comparison to Grossberg.”

The Grossberg installation marks the second time that works from Berman’s collection have been shown at the Harvard Art Museums; in 2016, a two-part installation focused on “The Ring,” an international graphic design group of a dozen artists, architects, and designers. Like that installation, this latest one will appeal to those interested in German art and design of the early 20th century.

“The work of Carl Grossberg adds an important dimension to the narrative of German art between the wars, and it is a story we have not yet been able to tell,” said Lynette Roth, the Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum and head of the Division of Modern and Contemporary Art. “The Busch-Reisinger Museum is dedicated to the art of German-speaking countries and its collections can provide the context for this work, so we are thrilled to be working with Merrill C. Berman to bring Grossberg’s art to a wider audience here in the United States.”

Short, Successful Career

Like many artists of his era, Grossberg’s life and career were punctuated by war. Born in Elberfeld, Germany, in 1894, Grossberg was an architecture student when he was drafted into World War I. Upon reentering civilian life, he studied painting with Lyonel Feininger at the Bauhaus and led a successful career in the 1930s as both an artist and an interior designer.

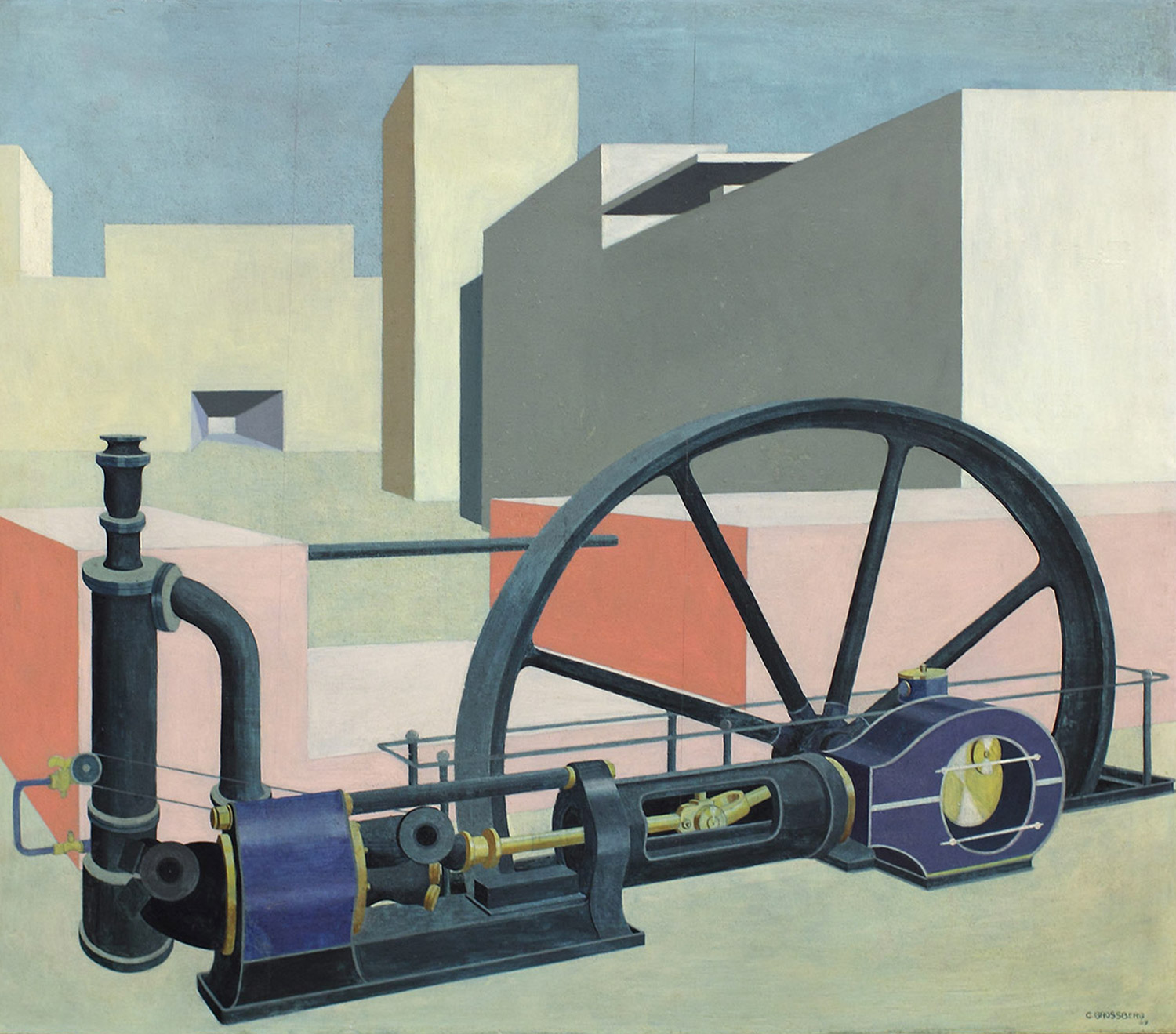

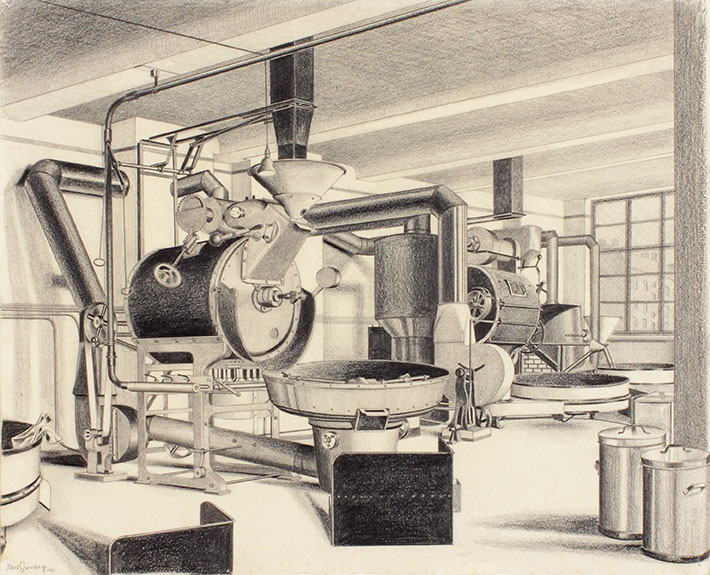

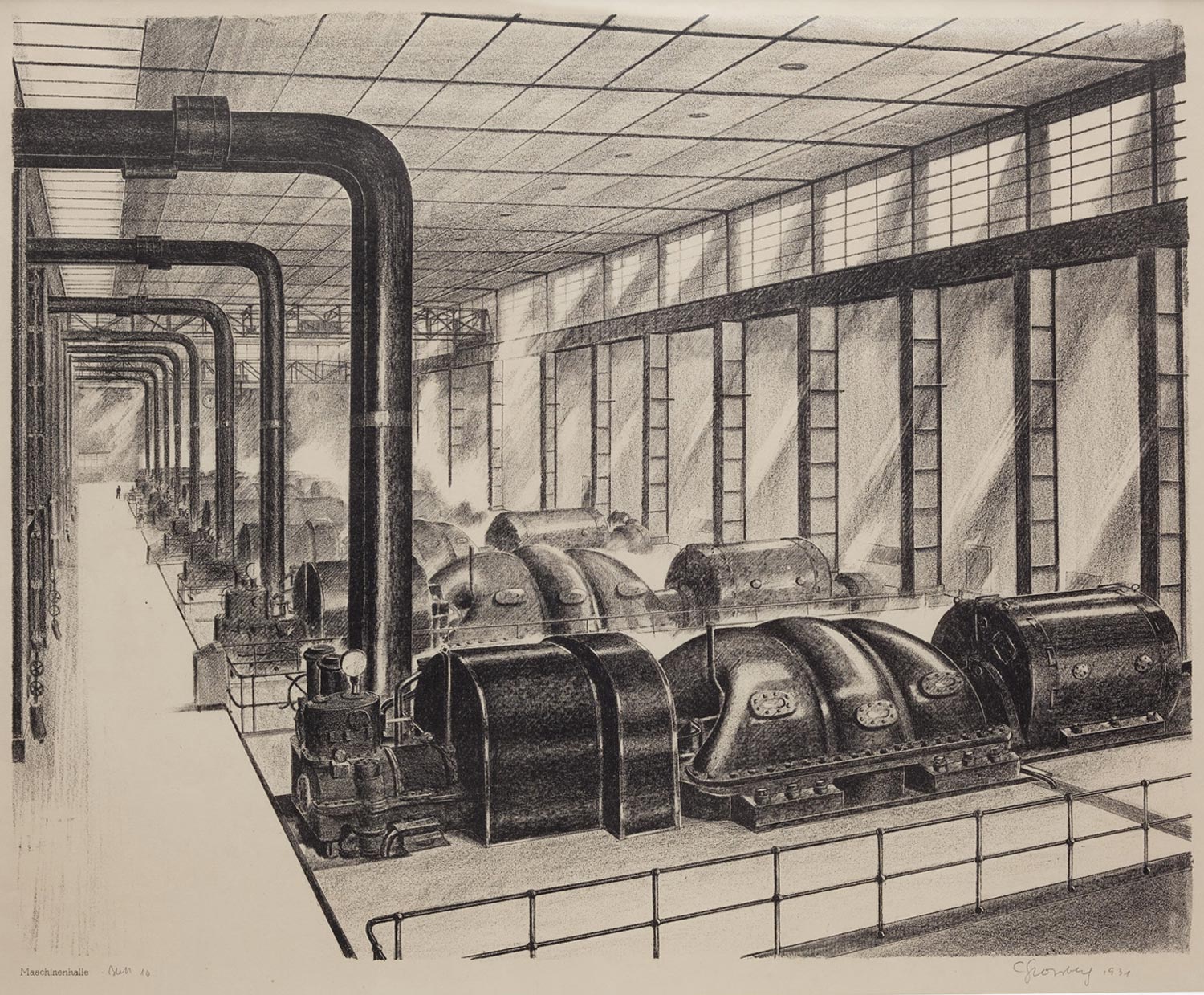

Grossberg quickly became known as a specialist in architectural and industrial subjects. He was fascinated with machinery, evidenced by the engines, storage tanks, and turbines in his machine portraits, such as Coffee Roaster (1933), Machine Hall (1931), and Textile Factory (1935). Each depicts factory equipment in meticulous detail—and in clean and gleaming idealized spaces without the workers who ran them or the chaos of operation.

“For today’s viewers, Grossberg’s affection toward machines might seem old-fashioned,” said Venator, who curated the installation. “But at the time Grossberg made these works, factories were icons of modernity and innovation. In the interwar period, industry was where the most impressive experiments were taking place in Germany.”

In Context

Revealing another glimpse into the era, the painting Berlin, AVUS (1928) takes as its subject the gatehouse to Germany’s first controlled-access highway, called “Automobile Access and Training Road,” or “AVUS.” When it wasn’t hosting races, the highway operated as a toll road and connected the Berlin neighborhood of Charlottenburg to nearby Potsdam. Today’s viewers of the painting will recognize signs advertising Mercedes-Benz and Fiat.

The subject of Interior (1935) may also be familiar to modern viewers. Depicting a model room of the sort Grossberg would have created in his career as an interior designer, the painting features tubular steel chairs just like those designed by Marcel Breuer at the Bauhaus in 1925—and like many still used in homes and businesses today. To underline Grossberg’s connection with the Bauhaus, a strength of the Busch-Reisinger collection (and the focus of a robust new Special Collection), an example of Breuer’s Club Chair (B3) is displayed beneath Interior.

“Within the broader topic of Weimar art, we tend to think of New Objectivity as occupying its own camp,” Venator said. “Grossberg was a New Objectivity artist, but he came out of the Bauhaus. You can see that the idea of industrial design was alive with him, and that the Bauhaus aesthetic and pedagogy could go in a lot of different directions for a lot of artists.”

As with much of Grossberg’s art, Interior contains unsettling or illogical details: upon closer examination, the table casts a shadow, but the chairs do not; the empty fruit bowl adds a sense of unease; and the view through the window looks patently fake. It’s yet another work that signals the artist’s affinity with surrealists, such as Max Ernst, whose Heavenly and Earthly Lovehangs in a neighboring gallery.

“You can enjoy Grossberg’s appealing colors and draftsmanship, as well as his windows into unfamiliar places and things, but when you really spend time with his work, you’ll also pick up on these strange and striking elements,” Venator said. “It’s not as much about conservative realism as you might think—and that’s what is so interesting.”