Every month, the Busch-Reisinger Museum’s new Instagram account @busch_hall hosts conversations with established and emerging scholars, contemporary artists, and museum peers on Instagram Live. Launched in February 2021, the @busch_hall Conversations series, generously supported by the German Friends of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, presents a variety of perspectives in a thoughtful yet relaxed format.

For our first Busch Hall Conversation, Lynette Roth, the Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum, spoke with Joseph Koerner, the Victor S. Thomas Professor of the History of Art and Architecture at Harvard, to consider evolving conceptions of the “Germanic” and how the Busch-Reisinger has always worn its unique identity on its sleeve. Roth and Koerner discussed how the museum, founded in 1903, has by historical necessity been reinventing itself ever since. Below is an excerpt of that conversation—we hope it inspires you to view their lively discussion in its entirety.

The following conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity and accuracy.

Lynette Roth: I’m very pleased to welcome Joseph Koerner, whom I’m sure many of you know as the Victor S. Thomas Professor of the History of Art and Architecture. Professor Koerner teaches and writes about the history of art in the late Middle Ages to the present day, with an emphasis on Northern Renaissance art. And of course, he has spent many years teaching with the collection of the Busch-Reisinger Museum and has written about it on a number of occasions, including the museum’s 100th anniversary in 2003.

It might be helpful for us to start literally at the beginning, because I’m not sure that everyone is familiar with the Busch-Reisinger Museum and its origins at the turn of the century as the Germanic Museum. Why would, in 1897, faculty at Harvard feel the need to propose a Germanic Museum?

Joseph Koerner: I think the most fascinating way of framing the Busch for me always has been that it’s a museum that is struggling with the idea of identity. Museums today wonder about, and often are troubled by, their identity, because there’s one identity that they want to put forward and then as circumstances, politics, and demography change, people need to reassess their identity.

In the case of the Busch, the problem of identity was there front and center in the beginning, which was a belief on the part both of German authorities and Kaiser Wilhelm II [who donated the museum’s collection of plaster casts], but also Germans in America. There was a belief that when Germans immigrated to the United States, they lost their ethnic identity. They blended too easily into the United States.

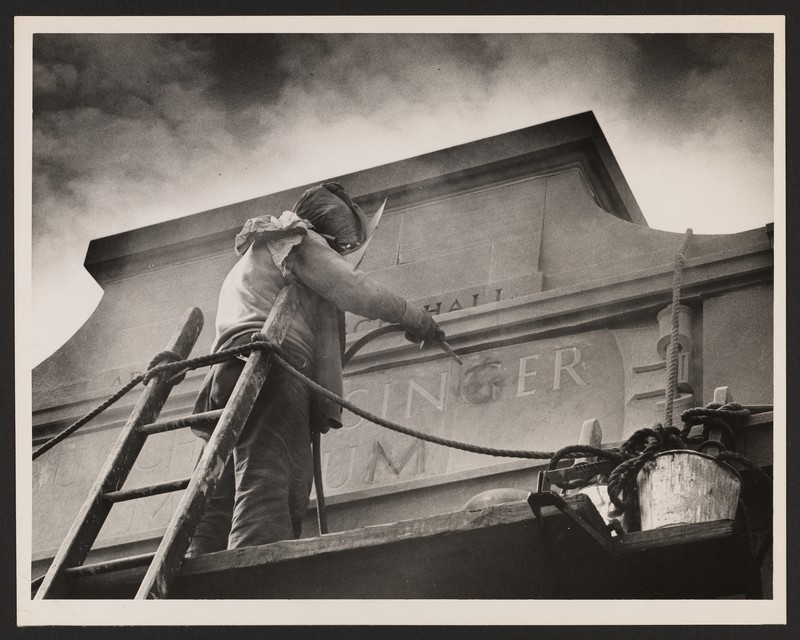

An idea took hold that there should be in the United States some place in which identity recollection, or identity reformation, could happen. And so a negotiation between Kaiser Wilhelm and Harvard faculty created a museum of photographs and casts, a historical museum—but at an inauspicious time. We’re right at the cusp of the end of the 19th century by the time the thing is built, and all the gelatin prints are coming in, and there are these beautiful things, all for historical identity formation reasons. World War I breaks out; then America joins the side against Germany, and then you have this white elephant, this strange formation in the middle of Harvard, a Germanic Museum. The term “Germanic” by the end of World War I was already very strange. If you think about intellectuals like Thomas Mann, after the First World War they’re writing books like The Magic Mountain[1924]. It’s all now totally in the rearview mirror. Then, of course, German identity comes up again in the crisis years between the wars, and the Busch-Reisinger gets a new identity when Hitler comes into power in 1933 and the democracy of the Weimar Republic goes away.