A menagerie of animal forms—bulls, rams, donkeys, lions, deer, and a hippo among them—fills our Animal-Shaped Vessels exhibition. Their origins span an astonishingly wide array of eras, cultures, and locations.

The enduring appeal of these unique objects is hardly surprising, said exhibition curator Susanne Ebbinghaus, the George M.A. Hanfmann Curator of Ancient Art and head of the Division of Asian and Mediterranean Art.

“The relationship between animals and humans has endured for millennia,” Ebbinghaus said. “Humans have always had close bonds with animals, and animals have been essential to human survival,” she said, noting the dual, and sometimes conflicting, role of animals as companion and food source.

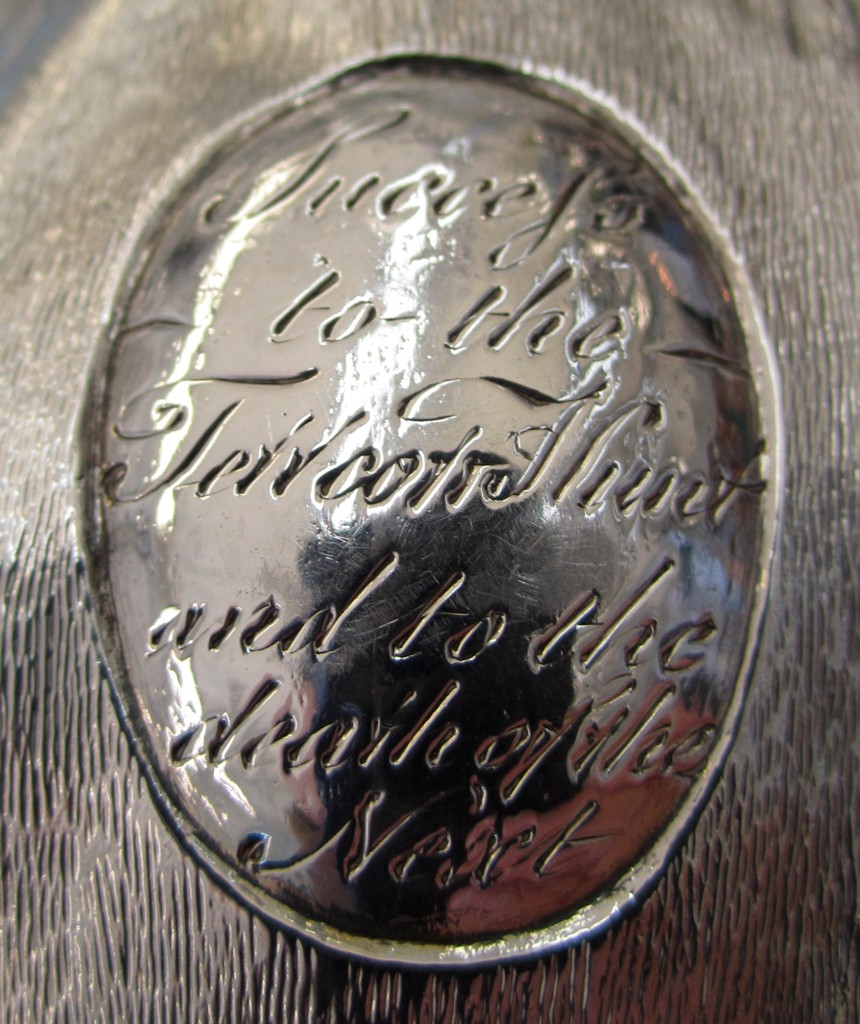

Animal-Shaped Vessels is replete with testaments to this powerful bond, in the form of drinking and pouring vessels. While the exhibition’s primary focus is on examples from the ancient world, these types of vessels have persisted into modern times. The exhibition includes a few striking objects from the past five centuries, such as an elaborate automaton (a self-propelled mechanism) from 17th-century Europe, an 18th-century English silver stirrup cup (used by hunters on horseback), and 20th-century drinking horns from West Africa and Europe.

“The modern objects in the exhibition are illuminating,” Ebbinghaus said. “They can tell us a little more about their users and contexts than most ancient vessels, which require us to try to reconstruct details from their appearance and the archaeological contexts in which they were found.”

Treasures in Silver

The automaton in the exhibition was created by an artist working in Augsburg, Bavaria—one of the most important centers of European goldsmithing in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. The partially gilded silver object comprises a statuette of the goddess Diana riding a stag, accompanied by two dogs and other animals. The stag and dog statuettes are hollow, with ample space to hold wine or other liquids, and a spring-driven mechanism hides inside the automaton’s base. The object might have been used as a table ornament or activated in a drinking game (called Trinkspiel).