Among the more than 2,500 pigments in the Forbes Collection of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies, there are plenty of unusual ones, but none is perhaps spookier (and more appropriate for Halloween) than mummy brown.

In 1904, the London firm C. Roberson advertised in the Daily Mail that “We require [a] mummy for making colour. Surely a 2,000-year-old mummy of an Egyptian monarch may be used for adorning a noble fresco . . . without giving offence to the ghost of the departed gentlemen or his descendants” (Woodcock 1996). Mummy brown, Egyptian brown, or caput mortuum (literally, “dead head” in medieval Latin) was a rich pigment varying in hue from burnt to raw umber, made primarily from white pitch, myrrh, and ground-up ancient Egyptians and their pets. Though originating in ancient Egypt, it became popular in European painting during the 16th–19th centuries and was favored by Pre-Raphaelite painters for its tone and texture (McCouat 2013).

In the 16th century, there was a thriving trade in mummified remains between Egypt and Europe. Mummy powder (mumia), said to have mystical curative potency, was sold in European apothecaries, to be applied to the skin or mixed into food and drinks (McCouat 2013). Perhaps the first description of its use in pigments is in an art treatise claiming that Europeans produced such colorants as early as the 12th century (Lomazzo 1584). However, it wasn’t until the 18th century that pigments from mummies came into fashion, with the “fleshiest parts” of the cadavers allegedly “providing the finest colours” (Compendium 1797). The popularity of this pigment can be seen in George Keate’s poem “Epistle to Angelica Kauffman” (1781), in which the poet praises the artist for over 32 pages of prose for allowing the mummy to live forever through her paintings. In the article “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy,” conservator and historian Sally Woodcock comments, “It is possible that it [mummy brown] continued to be popular for so long because it was easy to handle, gave an initially pleasing effect and artists were unable to resist the allure of painting with a material of such antiquity” (Woodcock 1996).

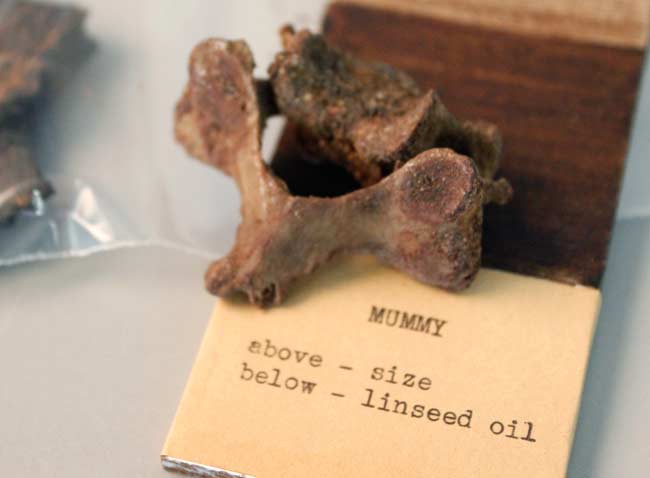

The color was mass-produced in shops across Europe; one 1712 Parisian art supply shop even cheekily called itself “À la Momie,” and sold mumia, paints, varnish, and incense. In 1809 George Field, a British chemist, recorded receiving a delivery of mummy from Sir William Beechey for the purpose of making the mummy brown pigment. Field described the delivery as arriving “. . . in a mass, containing and permeating rib-bone etc.—of a strong smell resembling Garlic and Ammonia—grinds easily—works rather pasty—unaffected by damp and foul air” (Finlay 2007).

By the end of the 19th century, the pigment fell from popularity because of bad press, its material instability, and difficulty in obtaining mummies. C. Roberson discontinued mummy brown in 1964. Managing director Geoffrey Roberson-Park told Time magazine they had run out of mummies: “We might have a few odd limbs lying around somewhere, but not enough to make any more paint” (Time1964).

Currently, modern synthetic versions, called mummy bauxite or caput mortuum, are available. However, it appears that the only use now for actual mummy brown is as fodder for ghost stories. In her book Color: A Natural History of the Palette, Victoria Finlay writes, “The Egyptians mummified their dead . . . because they believed that one day the Ka or spirit double would return. If this is the case, theKa might be kept busy for years, trotting sadly around the museums and art galleries of the world . . .” (Finlay 2007). We might then wonder what spirits roam the halls of the Harvard Art Museums.

R. Leopoldina Torres is a former Communications Intern (summer 2013) and is pursuing an MLA degree in the Museum Studies Graduate Program at the Harvard Extension School.

Anonymous, Compendium of Colours and Other Materials Used in the Arts (London: n.p., 1797).

Finlay, Victoria. Color: A Natural History of the Palette. New York: Random House, 2007.

McCouat, Philip. “The Life and Death of Mummy Brown,” Journal of Art In Society (2013).

“Techniques: The Passing of Mummy Brown,” Time, October 2, 1964, 126.

Woodcock, Sally. “Body Colour: The Misuse of Mummy.” The Conservator 20 (1996): 87.