Sarah Lewis has long been fascinated by the contested relationship between the arts, justice, and African American culture. She began to study the subject while an undergraduate at Harvard, inspired by art in the museums’ collections, such as Creation, from Jacob Lawrence’s Struggle series. She continued to explore the topic in curatorial positions at London’s Tate Modern and at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Now, having returned to Harvard as an assistant professor in the Departments of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies, she is inviting students and others to delve deeply into the same complicated and rich material that has absorbed her for so long.

Lewis is teaching a History of Art and Architecture course titled Vision and Justice: The Art of Citizenship, and has organized a complementary installation of the same name at the Harvard Art Museums. The University Teaching Gallery installation features photographs, prints, and watercolors from the 19th through the 21st century, all of which provide perspectives on race, art, and history (and all drawn from the Harvard Art Museums’ collections). Throughout the semester, Lewis’s students will visit the installation, closely studying individual objects and making important connections between the works, historical materials, and their own research.

The installation and the course are cousin projects to Aperture magazine’s special issue Vision & Justice (223; Summer 2016), which Lewis guest-edited. The issue examines the same topics within the same period (and features some of the same photographs) as the installation. Lewis said she hopes the installation serves as a “template for a larger exhibition that I will mount in years to come.”

Lewis recently spoke to us about how and why she created the installation, and her hopes for how viewers engage with the art.

How did you select the objects to include in the installation?

I wanted to make it synoptic of the very same chronology found in the Aperture “Vision & Justice” issue, such that the show would begin with representations of emancipation and slavery and extend through to images of contested citizenship seen today. This chronological sweep is important because the act of visual literacy is currently crucial for understanding race and citizenship, but it truly has been for centuries. So the guiding filter I used for selecting objects was to underscore this point.

The second criterion was to look at the ways in which three moments in American culture—emancipation, expansion, and the application of the Equal Protection Clause—can be understood through this nexus of vision and justice. By expansion, I mean spatially: understanding what it meant to move into the American West, but also what it meant to expand our idea of what constitutes citizenship. The Equal Protection Clause [is very relevant today]; we are still dealing with a moment where we’re trying to apply the equal protection clause for various groups.

What, if anything, surprised you as you curated the installation?

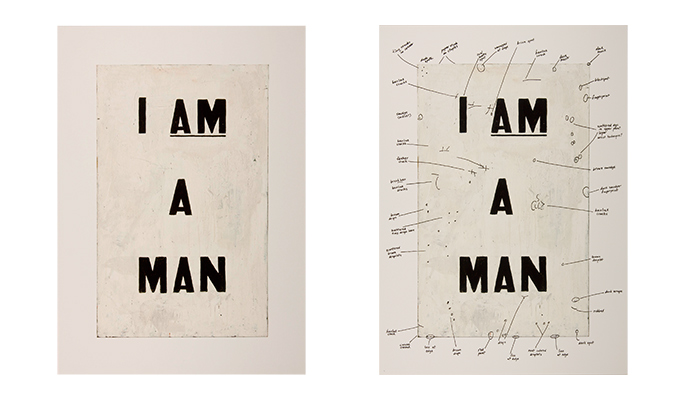

For me, there were a lot of surprises about the museums’ collections. I think the viewer might be surprised that this is not a show by artists of color about race and citizenship. Instead, by including works from Henry Louis Stephens to Bruce Davidson, Winslow Homer to Matt Heron, along with Gordon Parks, Kara Walker, Glenn Ligon, Lorna Simpson, and others, the exhibition shows the way in which artists, regardless of race, have together influenced and productively disrupted our notion of citizenship through aesthetics.

Your course and installation deal with the concept of visual literacy. What is visual literacy, and why is it important?

American citizenship has long been a project of vision and justice. Understanding the relationship of race and the quest for full citizenship in this country requires an advanced state of visual literacy, particularly during periods of turmoil.

We see this every day, as technology brings us events, circumstances, and different situations as an image. Regardless of our field of inquiry, we all need to have a level of visual literacy in order to be global citizens today, to understand the world. Why is this? We’re living in an increasingly polarized society; images—pictures, moving images—are increasingly the ways in which we bridge the gulf. Images also come to us with embedded narratives. They come to us as a kind of aggregate of an artist’s intentions, deliberate compositional choices, and references that one might not know without study.

So in the installation, I selected each object to both honor the mastery of the artist but also to remind the viewer of the visual literacy required for citizenship today.

With our access to images, and particularly to digital photography, today, are we becoming desensitized to the power of an individual image?

We are increasingly saturated with images. Lately I’ve been thinking through whether we have a visual bystander effect due to the image glut that surrounds us. The bystander effect is a term a psychologist coined in 1963, when, in Kew Gardens in Queens, New York, a woman was murdered in the dusk hours on the street, and it took a long time for bystanders to call for help because everyone thought someone else was doing something.

Is there a visual bystander effect? We can all witness—and many of us did—Eric Garner’s killing in that virally spread video, to give one of many examples; does that fact alter what animates us to act as citizens?

If there is a visual bystander effect, I think the way that we snap out of that is by finding and honoring works that get us to a productive point of stillness, or what my colleague Jennifer Roberts might call “immersive concentration”; pieces that decelerate you, that slow you down. And that’s what the work of a Kara Walker, a Glenn Ligon, a Lorna Simpson, a Gordon Parks does. That’s largely why these works are so important today. They move us to this point of enduring attention.

What do you hope visitors take away from the installation?

I hope visitors leave questioning this relationship of vision and justice and American citizenship. I hope it gives them a different filter through which to engage with objects that they see after the installation.

Looking at how we overcame societal failures and the connection with the arts is what made me interested in this relationship between vision and justice. And that might be something I hope the viewer takes away, too. Certainly, it is what I hope my students can take away—ultimately, a sense of the irreplaceable, perception-altering work of the arts for a national conversation about citizenship.